Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

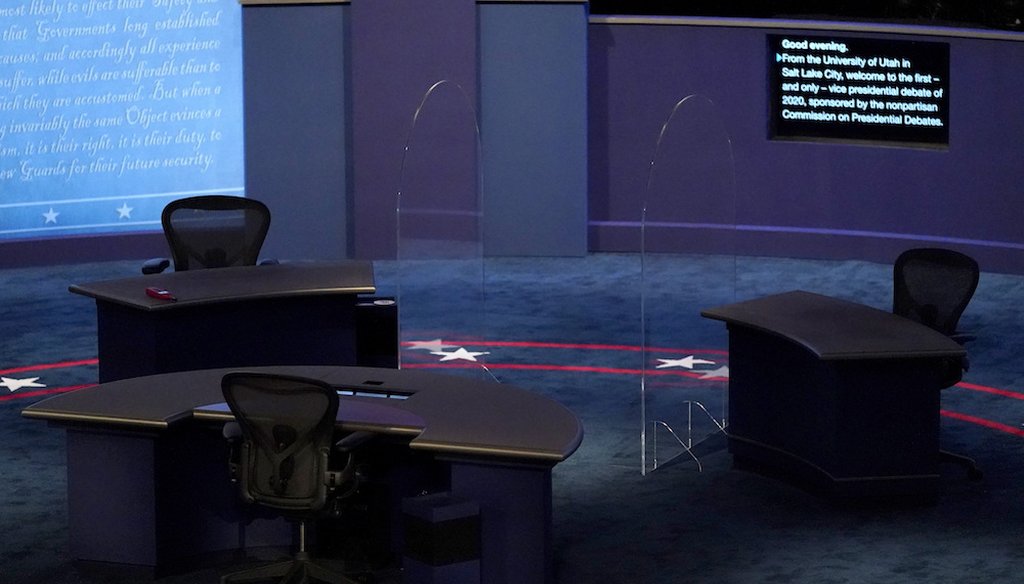

Plexiglass sheets separate Vice President Mike Pence and Democratic vice presidential candidate, Sen. Kamala Harris, D-Calif., in the debate Wednesday night. (AP Photo/Julio Cortez)

If Your Time is short

With everyone on stage already 12 feet apart, experts say the shields add little protection.

The coronavirus makes this election like no other, and its mark is in full view on the stage of the vice presidential debate. Organizers installed two large plexiglass shields to separate Republican Vice President Mike Pence and Democratic vice presidential nominee Kamala Harris.

After President Donald Trump contracted COVID-19, the Biden-Harris campaign insisted on the barriers. The Trump campaign pushed back, saying they were unnecessary, but ultimately relented.

The question is, are the barriers for show, or do they make a difference?

Two experts in the transmission of the disease say the plexiglass is more show than substance.

"Those barriers would pretty much only be useful if we were expecting the candidates to spit at one another," said Boston University epidemiologist Eleanor Murray.

Plexiglass shields are now commonplace at stores and service counters. They help in those places, because people are relatively close to each other. But for this debate, everyone is already at least 12 feet apart.

"What shields can do is block the tiny droplets that act like tiny cannon balls carrying the virus," said University of Maryland School of Public Health professor Donald Milton. "Those droplets don't fly much further than six feet. Any bigger distance than that, and the shields don’t make a meaningful contribution."

On the other hand, Milton said, there’s now general agreement — and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention just affirmed it — that smaller aerosol particles can carry the virus further.

"Plenty of that stuff could be suspended in the air and could be inhaled," Milton said.

If one of the candidates did sneeze in the other’s direction — not very likely — the plexiglass could even make the situation a little worse. Milton said that as the blast of air from the sneeze hit the edge of the barrier, it could create eddies that could swirl toward the candidate.

Both Milton and Murray say there’s a better solution than plexiglass.

"They should have fans and air filters removing any potentially infectious particles," Murray said.

Common household fans and air filters available at any hardware store would do the trick, Milton said. One set of fans would blow clean air toward each candidate, and another set would be positioned to draw air away.

For even better protection, Murray said there should be no spectators and both candidates would wear masks.

The event organizer, the Commission on Presidential Debates, requires everyone else in the hall to wear masks.

Our Sources

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Scientific Brief: SARS-CoV-2 and Potential Airborne Transmission, Oct. 5, 2020

Interview, Donald Milton, professor of environmental health, University of Maryland School of Public Health, Oct. 7, 2020

Email exchange, Eleanor Murray, assistant professor of epidemiology, Boston University School of Public Health, Oct. 7, 2020