Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

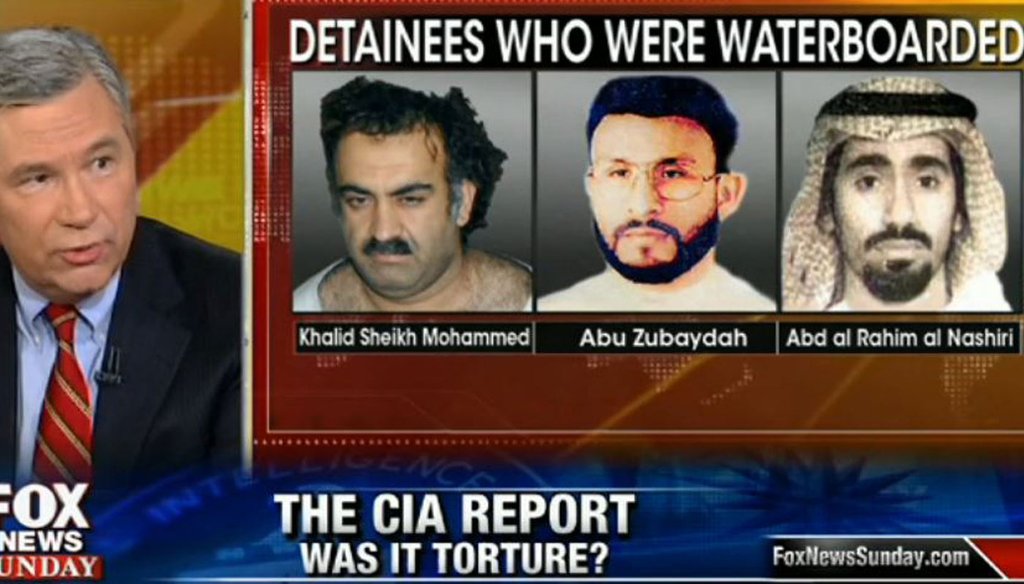

U.S. Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, D-RI, appearing on the Dec. 14 edition of "Fox News Sunday."

The so-called "CIA torture report" has heightened debate over whether certain interrogation techniques used by the United States in the wake of the Sept. 11, 2001 terrorist attacks constituted torture.

Rhode Island Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse weighed in on Dec. 14 when he appeared on "Fox News Sunday" with host Chris Wallace and political consultant Karl Rove.

In the portion of the program that dealt with whether waterboarding, which simulates the feeling of drowning, constitutes torture, Whitehouse said there was precedent in the United States to conclude that it was.

"We decided that waterboarding was torture back when we court-martialed American soldiers for waterboarding Philippine insurgents during the Philippine revolution," Whitehouse said.

"We decided waterboarding was torture when we prosecuted Japanese soldiers as war criminals for waterboarding Americans during World War II, and we decided waterboarding was torture when the American court system described waterboarding as torture when Ronald Reagan and his Department of Justice prosecuted a Texas sheriff and several of his associates for waterboarding detainees."

Because the Philippine revolution, which dates back to the 1890s, is the earliest reference Whitehouse made, we decided to check out that part of his statement.

While we were waiting for Whitehouse's office to respond to our request for documentation, we started poking around ourselves.

There's little doubt that what is now called waterboarding -- then known as water torture or by the odd name of the "water cure" -- was used by Americans in the Philippines after the U.S. gained colonial authority over the islands from the Spanish in 1898 under the terms of the treaty that ended the Spanish-American War.

Filipinos had been recruited to help fight the Spanish but when the Spanish were vanquished, the Filipinos tried to gain their independence. The resulting guerilla war had some things in common with the U.S. interventions in Iraq and Afghanistan, complete with boobytraps, suspicions that all Filipinos were guerrilla fighters, and the depiction of the guerillas as treacherous fanatics.

Most accounts we found report that an infantry captain named Edwin F. Glenn was found guilty of engaging in water torture during the war.

Glenn was a judge advocate at the time he was involved in waterboarding. By the time he was court-martialed, he had been promoted to major. He was specifically charged with administering the "water cure" to a prominent Philippine resident named Tobeniano Ealdama, whom he suspected of collaborating with insurgents.

Whitehouse's office cited a detailed 1903 Senate report on courts-martial in the Philippines. The section on Glenn accuses him of carrying out "a method of punishment commonly known in the Philippine Islands as the 'water cure;' that is, did cause water to be introduced into the mouth and stomach of the said Ealdama against his will" around Nov. 27, 1900.

Glenn admitted to the practice but defended it, arguing -- as waterboarding supporters do today -- that it saved lives. A military court didn't think that was sufficient justification. He was found guilty. But his sentence was light -- a one-month suspension and a $50 fine, which was the equivalent to more than $1,200 today.

Glenn wasn't the only soldier to be court-martialed for administering the "water cure," and testimony in the Senate report makes it clear that this was frequently used to extract information.

First Lt. Julien E. Gaujot, of the 10th U.S. Cavalry, was found guilty of doing it to three priests in January, 1902. He was suspended from command for three months, forfeiting $50 in pay per month for that period.

The military court made it clear that, in the cases of both men, the court was being lenient.

Like Glenn, Gaujot admitted using water torture, saying he did it because he knew the priests were insurgents and "I knew that they possessed information that would be valuable to the American cause."

"It was impossible to obtain reliable information regarding the insurgents from the inhabitants, who are, as a whole, crafty, lying, and treacherous, many of them being fanatical savages who respect no laws and whose every instinct is depraved," Glenn told the court.

Not all of the courts-martial were successful.

For example, 1st Lt. Edwin A. Hickman of the First U.S. Cavalry was brought up on charges for ordering that two Filipinos be held upside down and the upper half of their bodies dunked in an open spring to extract information and to get the men to act as guides. He admitted doing it but argued that it wasn't unlawful.

The court acquitted Hickman because of "the abnormal and disgraceful methods of armed resistance to the authority of the United States; the treachery of the natives generally; the paramount necessity of obtaining information, and the belief on the part of the accused that the punishment administered was within the rules of war and under the instructions of superior military authority."

In these cases, Judge Advocate General George B. Davis said General Order #100, which dated back to 1863, "contains the requirement that military necessity does not admit of cruelty -- that is, the infliction of suffering for the sake of suffering or for revenge -- nor of maiming or wounding except in fight, nor of torture to extort confessions." In these cases, there was no emergency that required torture, Davis argued.

One might debate whether the "water cure" is the same as waterboarding. In both cases, the victim is lying down and restrained. With waterboarding, the face is sometimes covered by a towel with the body tilted to try to keep water in the upper airways and out of the lungs.

With the water cure, water went directly into the mouth and was forced into the stomach, causing a great deal of pain. In both instances, the goal is not to drown the victim, but to make things as unpleasant as possible. Both produce the sensation of being unable to breathe.

Even if the water doesn't get into the lungs directly, the victim may vomit and inhale the vomit, which can be fatal.

The water cure was clearly effective in inducing fear. According to accounts in the Senate report, just the threat of repeating "the water cure" could be enough to break the will of recalcitrant Filipinos.

"At a minimum, the techniques are substantially similar," said Whitehouse spokesman Seth Larson.

Our ruling

Sheldon Whitehouse said the United States "decided waterboarding was torture back when we court-martialed American soldiers for waterboarding Philippine insurgents in the Philippine revolution."

The "water cure" as performed in the Philippines is not significantly different from the waterboarding done in reaction to the Sept. 11 attacks in 2001. Both forms of water torture -- and the risks -- are similar and the Senate report from 1903 makes it clear that military prosecutors regarded the "water cure" as a form of torture.

We rate the claim as True.

(If you have a claim you’d like PolitiFact Rhode Island to check, email us at [email protected]. And follow us on Twitter: @politifactri.)

ScribD.com, "Waterboarding in the Philippines," Report to the U.S. Senate, 57th Congress, 2nd session, Document No. 213, ordered printed March 3, 1903, accessed Dec. 16, 2014

The New York Times, "Defending the Water Cure," July 26, 1902

Alaska Dispatch News, "Glenn Highway Namesake Better Known for Torture in the Phillipines," Jan. 11, 2012

In a world of wild talk and fake news, help us stand up for the facts.