Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

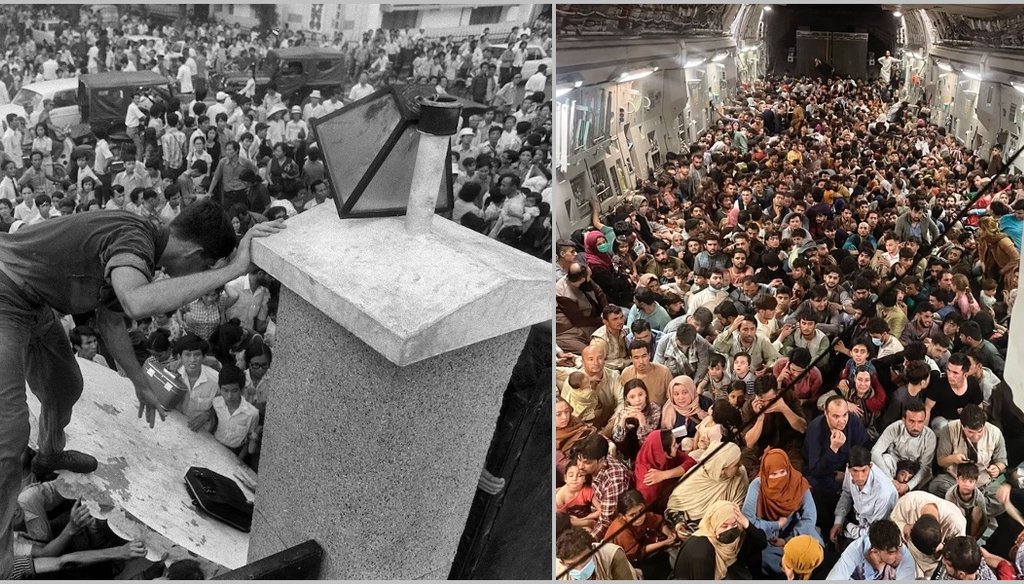

South Vietnamese civilians scale the U.S. Embassy wall in 1975 (left). Afghans crowded into a C-17 jet to escape the Taliban. (AP Photo/Neal Ulevich/U.S. Air Force))

In Saigon, April 1975, throngs of desperate Vietnamese people scaled the walls of the American embassy, hoping to get to any helicopter that would carry them away to safety.

In Kabul, August 2021, equally desperate Afghans mounted the walls of Kabul’s Hamid Karzai International Airport, and filled the runways, also hoping to find escape.

The parallels between the final hours of two wars that dragged on for years at huge cost and great loss of life struck many observers, including James Willbanks, a military adviser to the South Vietnamese in 1972 who wrote a key U.S. Army textbook on the Vietnam War.

"The evacuation of Saigon and Kabul looks pretty much the same to me," Willbanks told PolitiFact.

It also conjured difficult memories for those who escaped Vietnam in 1975, such as Thuan Le Elston. She wrote in USA Today, where she is a journalist:

"Former Vietnam War refugees have been watching Kabul in horror. Or unable to watch at all, not wanting to relive our fall of Saigon nearly five decades ago: U.S. military advisers and combat troops leaving after a couple of decades. Check. A corrupt government that failed its people. Check. Helicopters evacuating U.S. Embassy staff. Check. Long lines at different embassies of the desperate trying to get exit visas. Check. Run at the banks. Check. A cowardly president fleeing the country. Check. Kids in the backseat of cars fleeing with their families to God knows where. Check."

Even President Joe Biden invoked Vietnam in defense of his decision to pull U.S. forces out of Afghanistan.

"I made a commitment to the brave men and women who served this nation that I wasn't going to ask them to continue to risk their lives in a military action that should have ended long ago," Biden said Aug. 16. "Our leaders did that in Vietnam when I got here as a young man. I will not do it in Afghanistan."

The logic of that comparison might be unclear to millions of Americans who weren’t yet born when Saigon fell. The common threads are defeat, a heavy human and financial toll, and abandoned allies. But since no two wars are ever identical, there are both similarities and important differences in how they ended.

The two wars emerged from different geopolitical contexts, even if their ends were similar.

The Vietnam War was a flashpoint of the Cold War, the post-World War II global struggle between capitalism, led by the United States, and communism, led by the Soviet Union.

Vietnam had been split between north and south since 1954, when fighters with the Vietnamese Communist Party ousted the French, who had colonized the country for a century. The U.S. scuttled plans for a national election to reunify the country and stood up a government in the south. Fighting escalated after 1961. At times, both Russia and China supported the North Vietnamese.

By contrast, the United States’ recent involvement in Afghanistan followed the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, against the U.S. The attacks had been enabled by al-Qaida’s use of Afghanistan as its base. After the attacks, the U.S. teamed up with Afghan allies to oust the al-Qaida-aligned governing Taliban and, eventually, stand up what was intended to be a more inclusive government.

A man holds a certificate acknowledging his work for Americans as hundreds of people gather outside the international airport in Kabul, Afghanistan on Aug. 17, 2021. (AP)

The recent collapse of the American-backed Afghan army and government took about two weeks from the start of the Taliban offensive. The final reversal in Vietnam built gradually over the span of a year and a half, and some South Vietnamese forces resisted until the end.

First, Afghanistan. In May 2021, largely following a schedule struck by former President Donald Trump, the final 2,500 U.S. forces began to leave the country. By July, Bagram Airfield, the largest American base, no longer housed a single American soldier. The Taliban began taking over provincial capitals on Aug. 6. By Aug. 13, Taliban forces controlled Kandahar, the second largest city.

On Aug. 15, the Afghan president fled to Uzbekistan, and Taliban soldiers claimed victory.

In Vietnam, events played out much more slowly. The military and diplomatic context was quite different, and it’s worth reviewing a bit of the longer history.

By 1968, American forces topped half a million. A high death toll and a military draft to fill the ranks helped fuel an antiwar movement in the U.S., and America pivoted to turn more of the fighting over to South Vietnamese forces.

All parties signed a peace treaty in 1973, and in three months, the last American combat soldiers left Vietnam.

In early 1974, North Vietnamese forces began, slowly, to attack South Vietnamese units.

"The South Vietnamese Army fought for a year and a half after we left," Willbanks said. "They did a good job until they ran out of ammunition."

Unlike the Afghan forces, who walked away or surrendered immediately, the South Vietnamese army were initially able to hold off their enemies.

"In the case of Saigon, the advance of communist forces on the city was actually halted for nearly two weeks by the determined efforts of the South Vietnamese Army’s 18th division, which stood and fought at a town called Xuan Loc, located about 40 miles east of Saigon," said Dartmouth College historian Edward Miller.

Despite that, said George Washington University military historian Shawn McHale, the army ultimately crumpled.

"The South Vietnamese military lost half its military forces in a debacle," McHale said. "It was trying to retreat from the center of Vietnam, and this retreat turned into a rout."

McHale and other historians note some similarities. Both the South Vietnamese and Afghan forces had more sophisticated arms and air forces than the armies that defeated them. In neither case was that enough to prevail. One reason was that, in both cases, the governments and militaries that fell were considered corrupt and had insurmountable morale problems among their troops.

Taliban fighters stand guard at a checkpoint that was previously manned by American troops near the U.S. embassy in Kabul on Aug. 17, 2021. (AP)

The final North Vietnamese drive that would reach Saigon lasted 55 days. American officials saw the end coming.

Two weeks before Saigon fell, the White House National Security Council wrote April 11, 1975, "intelligence reports indicate the North Vietnamese Army have already decided to attack Saigon." Given the "current fragility of civilian and military morale and the apparent absence of leadership in Saigon," the memo said, the North Vietnamese "might be able to walk into town and take over."

"In Vietnam, it was clear for several months before Saigon’s final collapse that little could be done to stop the North Vietnamese," said Mark Lawrence at the University of Texas at Austin.

Today’s U.S. intelligence officials, on the other hand, seemed taken by surprise by the speed of the Taliban’s approach.

Biden said of the Taliban’s swift takeover, "This did unfold more quickly than we had anticipated."

But if Americans had more time to plan for getting out of Saigon, they didn’t use it well.

"A lot of the blame should be laid at the feet of the U.S. ambassador to Vietnam," said Nathan Packard, professor of military history at Marine Corps University. "The military realized this could go south pretty fast. They had plans in place (to evacuate). The ambassador refused to give that order. He thought it would look bad."

Biden hinted at similar concerns in a recent speech, but blamed the Afghan government, saying part of the reason more people weren’t moved sooner was that "the Afghan government and its supporters discouraged us from organizing a mass exodus to avoid triggering, as they said, ‘a crisis of confidence.’"

The final scenes from the American embassy in Saigon were of helicopter after helicopter landing in the embassy yard, ferrying people to ships close to shore. To make room on the decks for more arrivals, helicopters were pushed overboard into the sea. Thousands of South Vietnamese who had worked with Americans were evacuated, but many thousands more were left behind to fend for themselves.

South Vietnamese civilians try to scale the high U.S. Embassy wall in desperate attempts to get abroad on the evacuation flights in Saigon, Vietnam, April 30, 1975. (AP Photo/Neal Ulevich)

In both Vietnam and Afghanistan, Americans signaled that they had reached the limit of their engagement. President Richard Nixon and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger pressed for the peace treaty that gave the U.S. a way out after more than 15 years of fighting.

It was a "defective treaty," said Arthur Waldron, international relations professor at the University of Pennsylvania.

"It permitted — but did not require — U.S. action should it be violated," Waldron said.

When President Gerald Ford asked Congress to authorize renewed military action to stop the North Vietnamese advance in 1975, Congress said no.

Both Trump and Biden promised to end America’s military presence in Afghanistan, and committed to a date certain to leave.

The endgame may have been slower to come in Vietnam, but Willbanks said that in both conflicts, the American message was the same.

"We telegraphed that we were going home," he said. "We picked up our marbles and left."

If anything, ending the U.S. military role in Afghanistan enjoyed broader support than ending things in Vietnam, at least in the run-up to the U.S. departure, said Lawrence at the University of Texas.

"In 1975, the administration sought to pin blame on Congress for betraying South Vietnam, revealing a sharp partisan divide over the collapse of the American ally," Lawrence said. "This time, I think it’s clear that both parties supported the withdrawal from Afghanistan. There is no real constituency in the United States for carrying on the war or backing an Afghan regime widely regarded as hopelessly corrupt and ineffective."

U.S. Navy personnel aboard the USS Blue Ridge push a helicopter into the sea off the coast of Vietnam in order to make room for more evacuation flights from Saigon, Tuesday, April 29, 1975. (AP Photo/Jacques Tonnaire)

Both defeats leave Americans with lingering questions.

Would more assistance or a different exit strategy have produced a different outcome? What message does this send to other countries?

"You stand by your allies," said Willbanks. "We did not do that in Vietnam. And we are not doing it this time."

For other military historians, the key question concerns the limits of what American intervention can achieve.

"I’m surprised that we did this again," said Packard. "From a military standpoint, if you had to pick two of the hardest countries to operate in, Vietnam and Afghanistan would be high on the list. We think we can change the facts on the ground, if we just throw enough money at it. But we are aiming to get out. That’s not a path to success."

Our Sources

Army University Press, Vietnam: The Course of a Conflict, 2018

White House, Remarks by President Biden on Afghanistan, Aug. 16, 2021

AP, APRIL 30, 1975: SAIGON HAS FALLEN, accessed Aug. 16, 2021

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Selected Documents on the Vietnam War, accessed Aug. 16, 2021

Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Communist Plans to Attack Saigon and Implications of Evacuation Plan, April 11, 1975

University of Houston, Overview of the Vietnam War, accessed Aug. 16, 2021

PBS, Vietnam: Timeline, accessed Aug. 16, 2021

BBC, Afghanistan Timeline, Sept. 9, 2019

USA Today, "A timeline of the US withdrawal and Taliban recapture of Afghanistan," Aug. 15, 2021

Reuters, Kabul airport chaos stalls evacuations amid criticism of U.S. pullout, Aug. 16, 2021

Reuters, Taliban surge exposes failure of U.S. efforts to build Afghan army, Aug. 15, 2021

Email exchange, Michael O’Hanlon, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, Aug. 16, 2021

Email exchange, Fredrik Logevall, history professor, Harvard University, Aug. 17, 2021

Email exchange, Edward Miller, associate professor of history, Dartmouth College, Aug. 16, 2021

Email exchange, Arthur Waldron, Professor of International Relations, University of Pennsylvania, Aug. 16, 2021

Interview, Nathan Packard, Professor of Military History, Marine Corps University, Aug. 16, 2021

Email exchange, Mark Lawrence, professor of history, University of Texas-Austin, Aug. 16, 2021

Email exchange, Shawn McHale, professor of military history, George Washington University, Aug. 16, 2021

Interview, James Willbanks, former Director of the Department of Military History, US Army Command and General Staff College, Aug. 16, 2021