The movie is laced with expletives and explosives. But how much of it is based on real events?

It’s adapted from Stallworth’s memoir, which he published in 2014. The decorated 32-year law enforcement veteran wrote it using the investigation casebook he was ordered to destroy (but didn’t) by his sergeant in 1979.

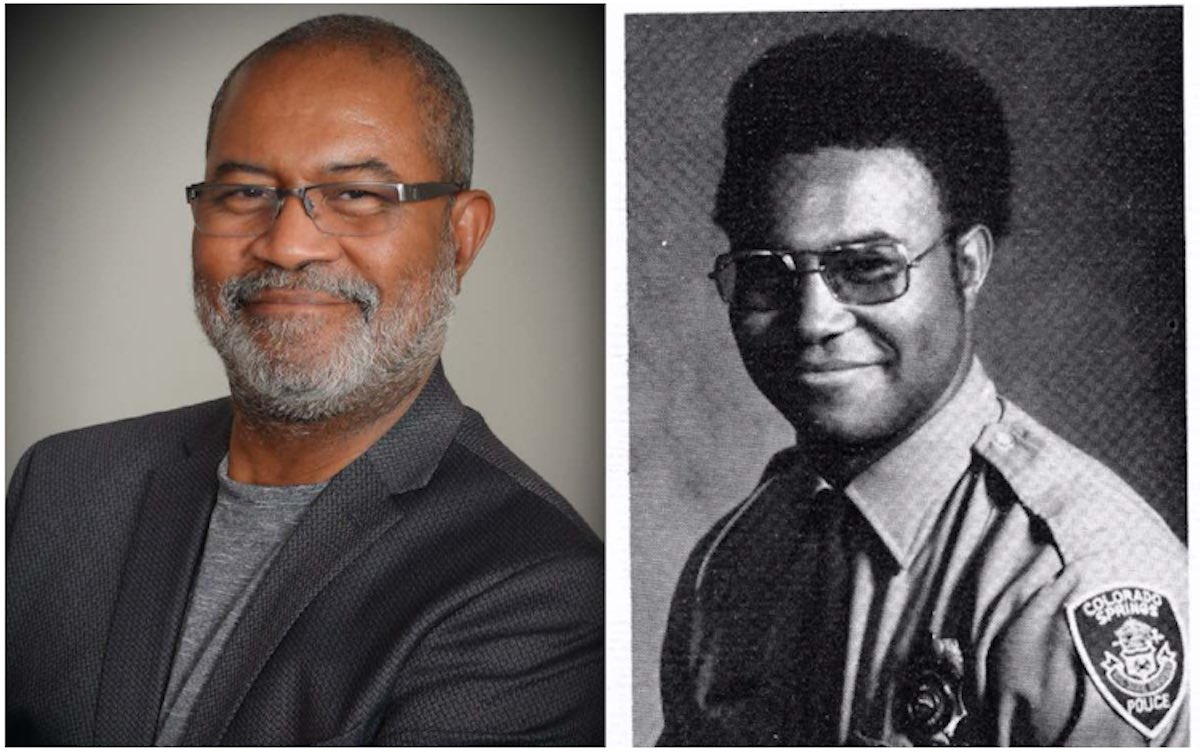

Ron Stallworth now, and at 22 in 1975. (Courtesy of Focus Features.)

To fact-check the movie, we relied on his account to verify the conversations between officers and the Klansmen as well as newspaper coverage at the time.

Here’s what’s real and what’s not.

In the movie: Flip’s Jewish identity almost compromised the operation.

In reality: Stallworth’s sidekick was not Jewish.

The movie kicks into gear when Ron, played by John David Washington, calls the number on a classified ad placed by the Ku Klux Klan in the Colorado Springs Gazette-Telegraph. He leaves a detailed message with his real name. Before the length of the message lapses, the phone rings. The Klan calls back.

In real life, time passed a little slower. Stallworth didn’t call, but expressed his interest to the Klan in a letter addressed to the post office box listed in a classified ad, according to his memoir. He also mistakenly gave away his real name in the note.

We found a couple of classified Ku Klux Klan ads in the Gazette-Tribune tucked between ads for dating services from that time period. One from Nov. 15, 1978, read, "Ku Klux Klan is forming. For information P.O. Box 4771, Colorado Springs, CO 80930."

The ads began running in June 1978, according to reporting in the Colorado Springs Sun by Nancy Johnson. The chapter leader, remaining anonymous, told Johnson the response had been "super fantastic," although many of the phone calls had come from black people who were worried about the Klan’s resurgence.

"They tried to disguise their accent, but even after 200 years of education by the white race, they can’t do it," he said, according to Johnson’s reporting.

Apparently, their radar was not that sharp.

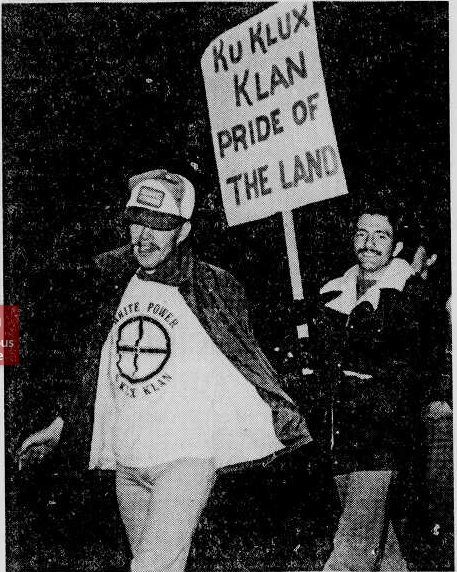

Kenneth O’Dell and Josef Stewart, the first and second in command of the Colorado Springs chapter of the Ku Klux Klan, during a Dec. 16, 1978 demonstration. (Photo by Dave Rains, courtesy of the Colorado Springs Gazette.)

Stallworth got a call back within two weeks, in November 1978. Kenneth O’Dell, the local chapter leader and a soldier stationed at Fort Carson, proposed a meeting. Stallworth described what he would look like with his colleague, Chuck, in mind: "I’m about five foot nine, 180 pounds. I have dark hair and a beard," Stallworth said. His whiteness was implied.

Chuck worked in the narcotics division. Stallworth has declined to disclose his name in both his memoir and interviews with the media.

Chuck’s availability was limited "because of both his narcotic workload and department politics," Stallworth writes. So the bulk of the investigation took place over the phone. He ended up being joined by another officer when the Klan insisted members bring recruits.

In the movie, however, Chuck is called Flip, played by Adam Driver, and has a much bigger role.

Here’s where the movie and reality begin to diverge. In the movie, Flip is Jewish. The real Chuck was not. Flip’s identity creates significant tension as he stands in for Stallworth during meetings with the Klan.

Felix, the second-in-command in the local Klan chapter in the movie, is wary of Flip from the moment they meet. He first accuses him of being a cop, and repeatedly presses him to prove he is not Jewish.

In one particularly tense scene, Felix locks Flip in a den with him in his basement. He tells Flip he has to take a lie detector test to make sure he is not Jewish. At one point, he whips out his handgun and threatens to examine Flip’s penis to see if he is "circumstanced."

Ron comes to the rescue, hearing the threat over the microphone in Flip’s shirt. He hurls a rock at the window, provoking Felix’s wife’s screams. Felix rushes to her rescue; Flip follows. They chase after Ron’s car, which Felix shoots at. Flip blocks the gun and takes it himself, shooting aimlessly at the road as Ron drives away.

None of that happened.

Stallworth said no guns were ever pointed at him during this investigation, and the Klan never cast doubts on his or his partner’s identities.

And no, Felix did not show up at Stallworth’s doorstep to discover a black man as he did in the movie.

In the movie: Stallworth reveals his identity to Duke in a phone call.

In reality: The conversation never took place.

O’Dell, the chapter leader, did once pick up on the difference in Stallworth and Chuck’s voices.

"The minute he heard my voice on the phone, he said, ‘What’s wrong with your voice?’ So I coughed, and then I said, ‘I have a sinus infection.’ He said, ‘Oh, I get those all the time. Here’s what you need to do.’ Then he proceeded to describe a remedy for me. That was the only time that my voice was challenged as being different from Chuck’s," Stallworth said in a recent interview.

But Stallworth does not recount being too careful in his telephone exchanges. After Duke told him he could tell a person was black by the way he pronounces "are" ("are-uh"), as he did in the movie, Stallworth recalls in his memoir he would always find a way to incorporate that pronunciation of the word into the conversation.

Topher Grace as David Duke in Spike Lee's BlacKkKlansman. (Photo courtesy of Focus Features.)

That leads us to the poignant conversation at the end of the movie, when Stallworth reveals to Duke that he’s been duped by a black detective. The real Stallworth talked with Duke following Duke’s visit, but Stallworth never revealed his identity. He cut off communication with the Klan and had his phone line changed when his superiors decide to end the investigation. His story only went public in 2006.

In an Aug. 7, 2018, radio podcast, Duke complained the movie portrayed him as a hateful buffoon. He did not, however, cast doubt on the book, which he said portrayed him as a "genius."

"The film even changes the facts in Ron Stallworth’s book, Black Klansman, to demonize me," Duke said. "They brag about how this guy conned me. Somebody calls me on the phone, I tend to trust people, I talk to people I’ve got nothing to hide. I say the same thing to everybody."

"Spike made him look kind of stupid," Stallworth told Lester Holt in an interview. "But he was stupid in how this whole thing transpired 40 years ago."

In the movie: Stallworth was Duke’s bodyguard during his Colorado Springs visit.

In reality: He was.

Duke’s visit to Colorado Springs was decked out in the movie. Two fancy black cars and a gang of motorcycles transport Duke to a church then a lodge for an ornate baptism of new Klansmen.

In real life, the baptism happened in one of the member’s apartment buildings. Duke did sprinkle holy water on them. Of the 12 new members, three were policemen: one was Chuck, another his partner, Jim, and a third officer from Denver.

They then watched the film Birth of a Nation, as they did in the movie.

The luncheon was the following day, but at a local steakhouse — not a fancy lodge. The real Stallworth was also summoned to provide security for Duke.

"There were no more than eight local Klansman at the luncheon," a Jan. 11, 1979, article in the Gazzette-Telegraph reads. "The small group also included two plainclothes policemen from a Denver suburb who were assigned to provide security for Duke and Fred Wilkins, a resident of the Denver suburb and head of the Ku Klux Klan in Colorado. A Colorado Springs detective sergeant was also assigned to Duke and Wilkins, and two Colorado Springs patrol cars were stationed in the parking lot of the restaurant."

That detective was the real Stallworth, according to his memoir.

In the movie, chants of "America first" hark back a little too conspicuously to the Trump era. Turns out they’re a reflection of history, according to the Sun reporter, Nancy Johnson.

"I thought for sure Spike Lee had just thrown that in to make the connection to present times. And I think a lot of people thought so, too," Johnson said. "But there it is in my story!"

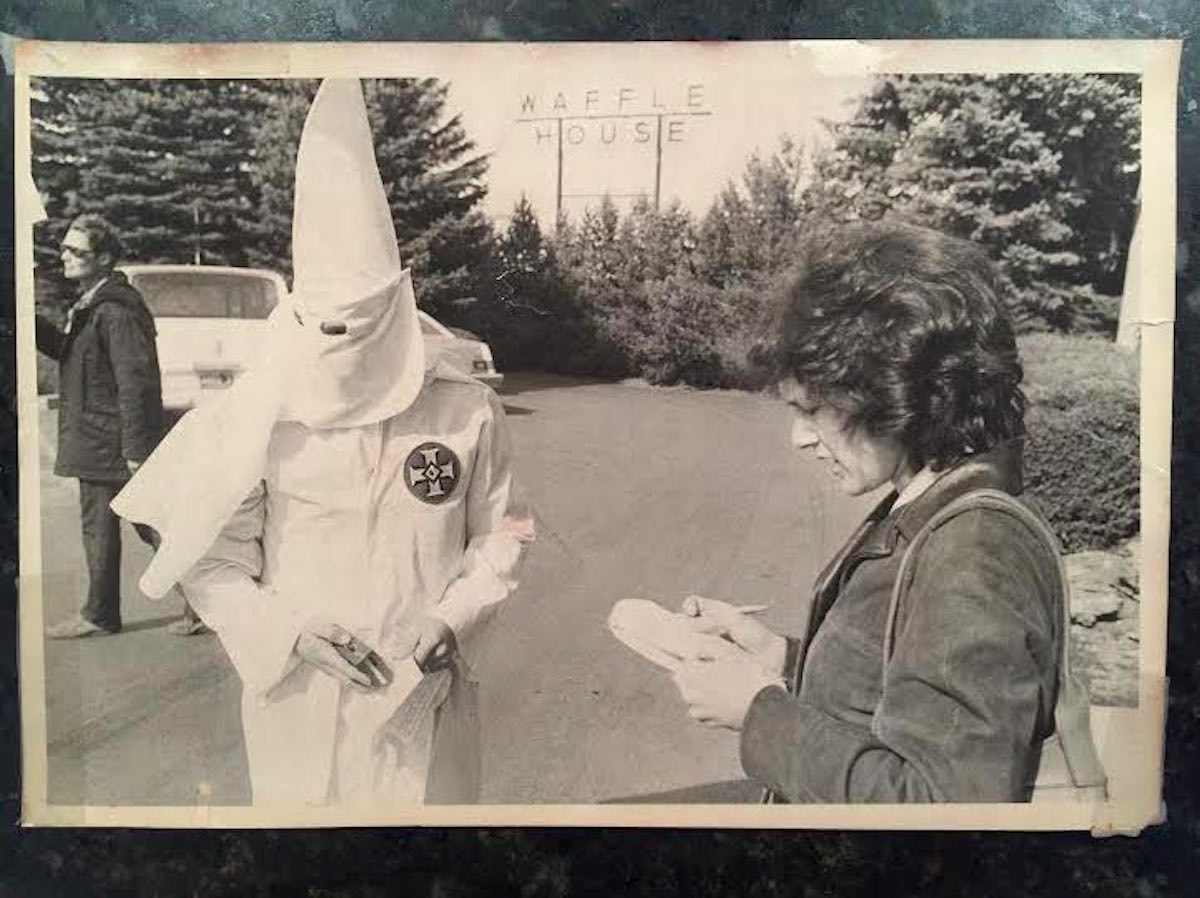

Nancy Johnson, reporter at the Colorado Springs Sun, interviews a Klansman in 1978. (Courtesy of Nancy Johnson.)

"The KKK stands for five principles," the June 30, 1978, Sun article reads. "The organization supports the white race, ‘America first,’ the United states Constitution, free enterprise and Christianity."

In the movie, Stallworth requests a photograph with Duke. He waits until Flip counts to three and wraps his arm around Duke’s shoulder, to which Duke reacts violently, and Stallworth warns him that assaulting a police officer could land him in prison.

According to Stallworth’s biography, that really happened. But he lost the Polaroid.

In the movie: Three Klansmen die in an explosion and one is arrested.

In reality: No C4 was stolen or set off, and no arrests were made.

The cheeky photograph is the highlight of the luncheon in Stallworth’s memoir. In the movie, three deaths and an arrest are the dramatic high point.

Connie, Felix’s wife, leaves the lunch abruptly with explosives — the same explosives that mysteriously went missing from the local army base. Her plan is to set a bomb off at a Colorado College Black Student Union gathering. She fails, however, because cops swarm the area. So she reverts to plan B: placing the bomb outside the house where Patrice, the BSU president and Ron’s girlfriend, lives.

She gets scared as Patrice approaches the house and places the explosives in her car instead. Three Klansmen come to pick her up, believing the C4 is in the mailbox. But it’s in the car, which they are idling beside. All three blow up as they flip the switch. After assaulting Ron, in spite of his yells that he is undercover, the police eventually arrest Connie.

None of that happened. No explosives went off, and no arrests were made during the investigation. (The racist cop, based on a real police officer in the Colorado Springs Police Department, was not arrested, either.)

There were explosives in real life, however. The Klansmen discussed bombing two gay bars during Stallworth’s investigation and in May 1982, the Colorado Springs Police Department made 10 arrests in relation to a ring that was manufacturing bombs and selling explosives. Four of them had ties to the Ku Klux Klan.

Patrice’s character isn’t real, either. In the movie, Stallworth starts a romance with Patrice, whom he meets while being inducted into the investigations unit. In reality, Stallworth started dating his future wife just before his investigative work began..

The Colorado College Black Student Union did participate in protests of the Klan, but the main opposition came from the International Committee Against Racism, a branch of the Progressive Labor Party. Stallworth infiltrated the PLP alongside the KKK, cozying up to organizers and showing up at meetings so he could alert police to marches and potential violence.

In the movie: The Klan burns one cross.

In reality: They denied responsibility.

Stallworth acknowledges the less exciting conclusion of his investigation in his book.

"I have often been asked, ‘What did you really accomplish over the course of this investigation without arresting any Klan members or seizing any illegal contraband?’

"My answer is always in this fashion: ‘As a result of our combined effort, no parent of a black or other minority child, or any child for that matter, had to explain why an eighteen-foot cross was seen burning at this or that location – especially those individuals from the South who, perhaps as children, had experienced the terrorist act of a Klan cross burning.’ "

Stallworth’s investigation prevented three cross burnings, he said in an interview.

In the movie, two North American Aerospace Defense Command officers form part of the Ku Klux Klan. That checks out with Stallworth’s memoir. The officers reportedly had top-security-clearance. NORAD discovered their membership in the Klan through Stallworth’s investigation, as he acquired a list of all chapter members. He was then told they "would be transferred by the end of the day to the ‘North Pole,’ the farthest northern military installation in the U.S. command," Stallworth writes. Stallworth, however, never learned their identities.

We were unable to verify that. But the two Klansmen in real life, O’Dell and Josef Stewart, were Army sergeants at Fort Carson. Both were issued leave in November 1978 following the Colorado Spring Sun’s reporting on their military links.

Stallworth’s story ends in the movie with a cross burning. A large group of cloaked Klansmen set a towering cross aflame in the middle of a field.

Something similar happened in real life. Stallworth concluded his investigation at the behest of his bosses on March 30, 1979, when the Klansmen insisted that he become their new leader (as in the movie).

20 members of the Colorado Springs Ku Klux Klan marched in protest of Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s speech on a black teenager who was convicted for murder on March 30, 1979. (Photo by Dave Rains, courtesy of the Colorado Springs Gazette.)

That night, five men "dressed in white" lit a cross on fire outside a local nightclub, where a fundraiser for a black teenager who was convicted for murder was taking place, according to an April 1, 1979, Gazette-Telegraph report.

The Klan denied responsibility. O’Dell told the reporter only three members of the Colorado Springs chapter own the traditional white Klan robes, so it couldn’t have been them.

Lee ends the film with a montage from Charlottesville, Va.. The footage shows the white nationalists’ march on the University of Virginia campus and the street protest that resulted in the death of Heather Heyer. That really happened.