Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

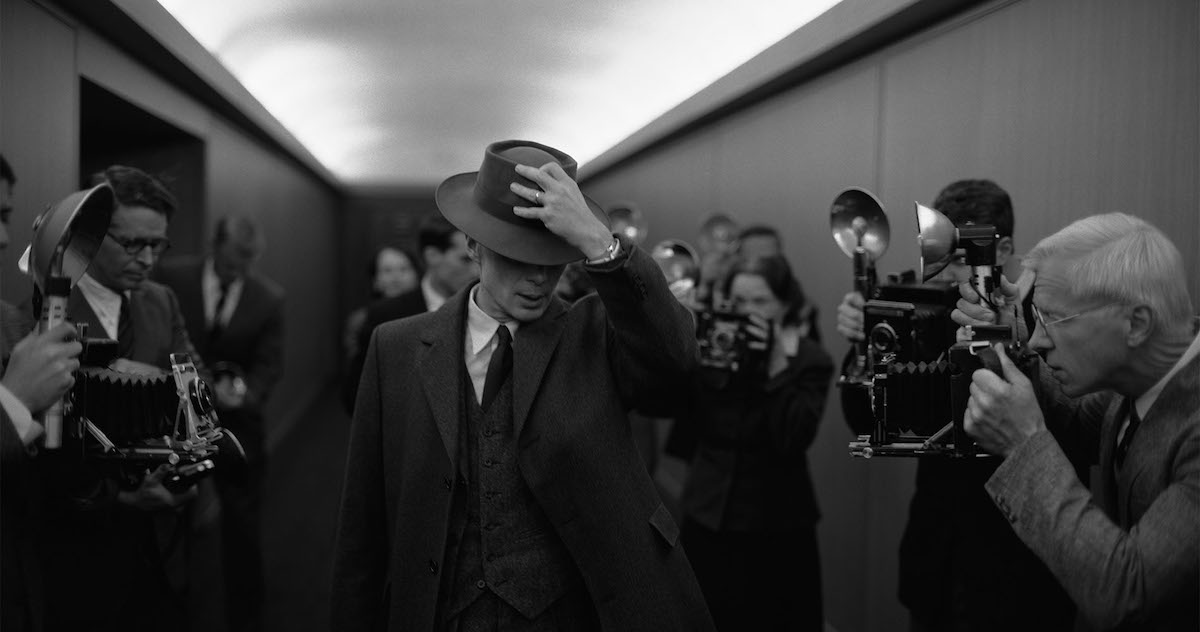

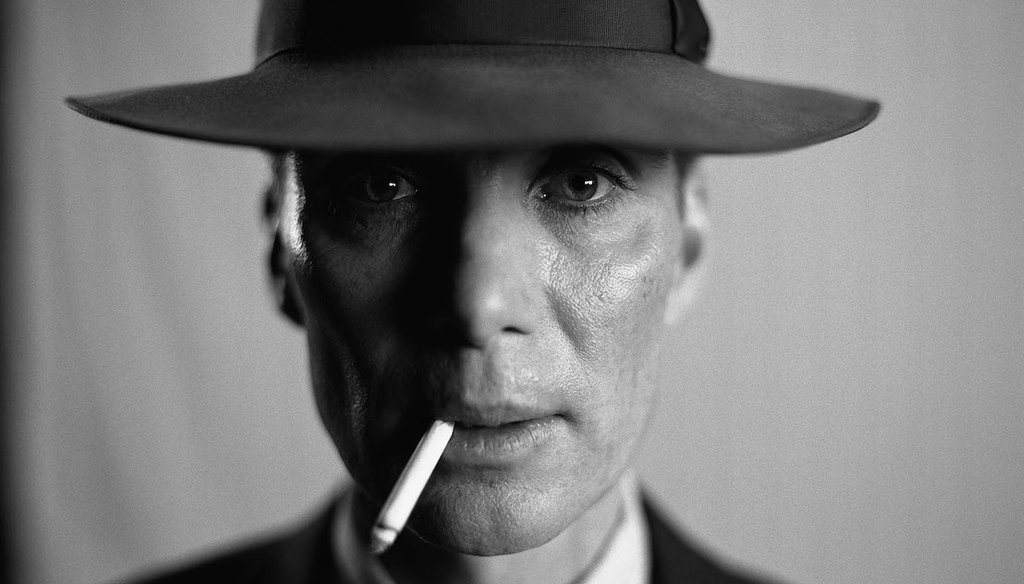

Cillian Murphy plays J. Robert Oppenheimer in Christopher Nolan’s “Oppenheimer.” (Universal Pictures)

If Your Time is short

-

The movie “Oppenheimer” hews close to the historic record, but takes a few liberties.

-

Two of the scenes with Albert Einstein are invented, but there’s a deeper underlying accuracy.

-

After more than six decades of effort, the movie factored in a 2022 Cabinet-level order to restore Oppenheimer’s reputation.

The movie "Oppenheimer" is less about the bomb and more about the trials — both moral and political — that beset J. Robert Oppenheimer. Oppenheimer was the World War II physicist who spearheaded America's race to beat the Nazis before they could invent an atomic bomb.

But to the extent that this is a war story, it’s about the Cold War and the anti-Communist fever that tore through the U.S. even before Germany and Japan surrendered. The movie doesn’t begin with the development of the bomb at a top secret lab in Los Alamos, New Mexico, but in 1954, with Oppenheimer defending his American loyalty before a hostile panel in a cramped Washington, D.C., conference room.

The film shifts back and forth from that conference room to scenes of Oppenheimer’s guiding role in the development of the bomb to a 1959 Senate hearing that reveals the darker forces of Washington. Scriptwriter and director Christopher Nolan drew heavily on the historical record, and in all important ways, he hewed to the facts.

But he did invent a few things, and he simplified others, for the sake of crafting a gripping tale. Fair warning: As we compare what’s in the film with what really happened, we spoil a few surprises.

In one scene, physicist Edward Teller flags the possibility that the bomb will set off a chain reaction that would ignite the atmosphere. Oppenheimer asks Einstein to check it out. That discussion never happened. Oppenheimer did consult a fellow physicist, Arthur Compton.

Nolan acknowledged this in an interview with The New York Times, saying he brought in Einstein, because he was "the personality people know in the audience."

The film accurately shows Los Alamos physicist Hans Bethe run the numbers and declare that the scenario couldn’t happen.

The other invented scene with Einstein comes at the very end. The two men stand by a still pond on the grounds of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. It is set in 1947, when Oppenheimer became institute director, joining Einstein, who had been there for many years.

The conversation is fictional, but the two worked together, and the script tracks with the views they held.

In 1947, Oppenheimer was still riding high, celebrated as the father of the atomic bomb. In the film, Einstein warns Oppenheimer of fame’s fickleness.

"It’s your turn to deal with the consequences of your achievement," Einstein says. "And one day, when they have punished you enough, they’ll … give you a medal. And tell you that all is forgiven."

Einstein had no use for politicians. In 1951, during the years of McCarthyism and anti-Communism run amok, Einstein wrote to an acquaintance, "People acquiesce without resistance and align themselves with the forces of evil."

At the end of the scene by the pond, Oppenheimer recalls the worry before the first test that "we might start a chain reaction that would destroy the entire world." Einstein nods, and Oppenheimer adds, "I believe we did."

Both men feared the power that had been unleashed. Oppenheimer pressed President Dwight D. Eisenhower to minimize the threat of a nuclear arms race and to set the American public straight on atomic weapons’ immense destructive capacity. Einstein was a pacifist who championed nuclear disarmament.

In the film, Oppenheimer expressed a desire to combine physics and New Mexico, and he found a way to do so when it was time to select a location for the central laboratory code-named Project Y. In real life, he had a ranch in Albuquerque and suggested New Mexico as an option, deeming the Sangre de Cristo mountains remote enough for a secret town. Manhattan Project Director Lt. Gen. Leslie Groves chose Los Alamos, which is about 35 miles from Santa Fe, New Mexico.

While inspecting the site in the film, Oppenheimer said Los Alamos had a boys’ school to commandeer and that the local Native Americans come for burial rites, but "after that, nothing." After Groves made the decision to "build the town," Oppenheimer projected the site would open in two months.

This is a simplification. According to the Atomic Heritage Foundation, most of the 50,000 acres used for the Manhattan Project already belonged to the government, but about 8,900 acres were privately owned. There were two dozen homesteaders and two larger properties — the Los Alamos Ranch School and the Anchor Ranch.

The Los Alamos Ranch School, started in 1917, trained young men through "rigorous outdoor living and classical education." On Dec. 7, 1942, the school’s director received a letter from U.S. Secretary of War Henry Stimson that said the U.S. Army was taking over the school’s property. Early arrivals to Los Alamos resided in the school’s buildings.

The owners of both properties negotiated sale prices — the school got paid $225 per acre, while the Anchor Ranch was paid $43 per acre. However, the Hispanic homesteaders were paid only $7 an acre, and their heirs later sought reparations. Some landowners did not receive their payments.

Many Hispano — Mexican or Spanish descendants in northern New Mexico — and Native workers returned to Los Alamos to work for the Manhattan Project.

James Remar, who portrayed Stimson, improvised the dialogue in which Stimson removes Kyoto from the list of targets because that’s where he had his honeymoon.

According to The New York Times’ interview with Nolan, actors came into the shoot with their own research, allowing them to "improvise" the discussion. When Remar mentioned that Stimson and his wife honeymooned in Kyoto, Nolan told him, "Just add that."

Although Stimson went to great lengths to keep Kyoto from being targeted, records don’t support the claim that he honeymooned there. According to historian Alex Wellerstein, none of the serious, scholarly accounts about the Kyoto incident or Stimson’s writings mentioned that he spent his honeymoon in Kyoto. Wellerstein noted that Stimson and his wife visited Kyoto in 1926, more than 30 years after their wedding. He also visited Kyoto for one night in 1929.

In 1959, Lewis Strauss, a staunch Republican, faced a Democratic majority in his Senate confirmation hearing to be commerce secretary. Watching the movie, you could be forgiven for thinking the Oppenheimer affair was the only hurdle Strauss faced. It was more than that.

The opening attack on Strauss came from Sen. Estes Kefauver, D-Tenn. Kefauver focused not on Oppenheimer, but on a 1955 botched power plant contract that took place on Strauss’ watch as head of the Atomic Energy Commission and that cost the government $1.8 million to settle legal claims.

Sen. Clinton Anderson, D-N.M., accused Strauss of hiding key information on nuclear policies from the Senate. Sen. Eugene McCarthy, D-Minn., said a vote for Strauss amounted to "approval of the unwarranted extension of executive secrecy."

In the final vote, two Republicans joined 47 Democrats to scuttle Strauss’ confirmation.

This leads to one other embellishment in the movie.

An aide tells Strauss there were three holdouts, "led by the junior senator from Massachusetts, young guy, trying to make a name for himself … John F. Kennedy."

Nolan takes poetic license with the politics. The vote margin is correct, but Strauss’ bid cratered thanks to the two Republicans. If they had voted his way, he would have prevailed. And every Democrat who was angling to be president, including Lyndon B. Johnson, Hubert Humphrey and Stuart Symington, voted against Strauss.

A solid paper trail ties Strauss to the attack on Oppenheimer.

"American Prometheus" pinpoints the day that Strauss launched his campaign to topple Oppenheimer: May 25, 1953. That day, Strauss told Eisenhower that Oppenheimer’s communist sympathies were not to be trusted.

Cillian Murphy plays J. Robert Oppenheimer in "Oppenheimer." (Universal Pictures)

Strauss put the wheels in motion to unseat Oppenheimer even earlier. In April 1953, he met with William Borden. Borden ultimately wrote a letter to the FBI that said, "More probably than not, J. Robert Oppenheimer is an agent of the Soviet Union." That letter started Oppenheimer’s downfall.

Soon after his April meeting with Strauss, Borden signed out Oppenheimer’s security file from the Atomic Energy Commission’s secure document vault. Borden was a top congressional staffer on atomic policy and had the proper clearance, but even though he left his job at the end of May, he kept the file until Aug. 18. By then, Strauss was fully installed as the commission’s chair.

After Borden returned the file, Strauss immediately signed it out and didn’t return it to the commission’s security vault until Nov. 4. Three days later, Borden sent his letter to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover that called Oppenheimer a Soviet agent.

Harold Green, counsel to the commission’s security division at the time, wrote that people in the division told him that Strauss had promised Hoover that he would get Oppenheimer out of the way.

The proof of Strauss’ fingerprints on the purge of Oppenheimer grows from there. Strauss handpicked the panel that would prosecute Oppenheimer and set the ground rules that blindsided Oppenheimer’s lawyers. He had access to the FBI’s wiretaps on calls between Oppenheimer and his lawyers.

The hearing itself was as grueling as the movie presents.

Anti-communist fervor’s full force was trained on Oppenheimer, and little artistic embellishment was needed; in 2014, the U.S. Energy Department released the entire transcript, giving the filmmakers ample material to include in the script verbatim.

Despite finding "no evidence of disloyalty," the panel and then later the full Atomic Energy Commission voted to strip Oppenheimer of his security clearance, and from then on, he was cut off from the government’s official nuclear policy discussions. He remained head of the institute in Princeton and became a sought-after speaker, writing and lecturing on science’s role in the nuclear age.

There’s not much you can do for someone who’s been dead for more than half a century, but on Dec. 16, 2022, Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm vacated the Atomic Energy Commission’s 1954 decision. Oppenheimer’s colleagues had been asking for that for decades, starting immediately after the commission ruled against him.

Indirectly, the Oppenheimer film helped reverse the black mark on his reputation.

In March 2022, filming was underway at Los Alamos. Kai Bird, one of the authors of "American Prometheus," was invited to visit the set and have dinner with Los Alamos National Laboratory Director Thom Mason. As the two spoke, Bird made a simple point about Oppenheimer’s security clearance hearing.

"What was done to him was unfair and a complete abuse of the kind of legal authorities under which (security) clearances operate," Mason told PolitiFact.

Seen this way, someone didn’t need to challenge the panel’s findings; what was wrong was the deeply flawed process. Mason took that point to eight previous lab directors, and on April 5, 2022, they sent a letter to Granholm asking her to reverse the commission’s decision.

In August 2022, 43 U.S. senators made a similar request. It was mostly Democrats who signed on, but four Republicans did too, including Sens. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., Marco Rubio, R-Fla., James Inhofe, R-Okla., and Lisa Murkowski, R-Alaska.

The push had everything to do with how the deck was stacked against Oppenheimer. This was hardly news. A 1959 internal Atomic Energy Commission review found that "the system failed . . .[(and) that a substantial injustice was done to a loyal American."

CORRECTION: This story has been updated to refer to former FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

Our Sources

The New York Times, Christopher Nolan and the Contradictions of J. Robert Oppenheimer, July 20, 2023

Scientific American, Bethe, Teller, Trinity and the End of Earth, Aug. 4, 2015

(The Impossibility of) Lighting Atmospheric Fire, Feb. 16, 2015

Inside Science, The Fear of Setting the Planet on Fire with a Nuclear Weapon, July 15, 2020

Ignition of the atmosphere with nuclear bombs, Aug. 14, 1946

The National WWII Museum, Making Public What Was Once Secret: Los Alamos and The Manhattan Project, May 11, 2022

Atomic Heritage Foundation, Leslie R. Groves, accessed Aug. 22, 2023

Atomic Heritage Foundation, Civilian Displacement: Los Alamos, NM, July 26, 2017

The New York Times, Land for Los Alamos Lab Taken Unfairly, Heirs Say, Aug. 27, 2001

Atomic Heritage Foundation, Hispanos in Los Alamos, June 28, 2017

Nuclear Secrecy Blog, Henry Stimson didn’t go to Kyoto on his honeymoon, July 24, 2023

Federation of American Scientists, Transcript Of 1954 Oppenheimer Hearing Declassified In Full, Oct. 6, 2014

U.S. Department of Energy, J. Robert Oppenheimer Personnel Hearings Transcripts, Dec. 16, 2022

New York Times, Transcripts Kept Secret for 60 Years Bolster Defense of Oppenheimer’s Loyalty, Oct. 11, 2014

Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, The Oppenheimer case: A study in the abuse of law, September 1977

U.S. Department of Energy, Unlocking the Mysteries of the J. Robert Oppenheimer Transcript, Oct. 3, 2014

U.S. Department of Energy, Secretary Granholm Statement on DOE Order Vacating 1954 Atomic Energy Commission Decision In the Matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Dec. 16, 2022

U.S. Department of Energy, Secretarial Order in the matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, Dec. 16, 2022

The New York Times, AEC prize going to Oppenheimer, April 5, 1963

The American Presidency Project, Remarks Upon Presenting the Fermi Award to Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, Dec. 2, 1963

Washington Evening Star, Strauss choice of Erpf for transport study hit, May 28, 1959

Congressional Quarterly Almanac, Strauss Nomination, 1959

U.S. Department of Energy, Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Testing: 1951-1963, September 2006

CQ Almanac, Dixon-Yates Contract, 1955

Time, THE ADMINISTRATION: The Inquisition, May 18, 1959

National Archives, Lewis Strauss and Robert Oppenheimer, July 24, 2023

California Institute of Technology, J. Robert Oppenheimer on the Caltech campus, accessed Aug. 15, 2023

Letter to Sec. Granholm from Los Alamos lab directors, April 5, 2022

Letter to Sec. Granholm from U.S. Senators, Aug. 8, 2022

"American Prometheus", Kai Bird and Martin Sherwin, Knopf Doubleday, 2006

Engineering and Science, Albert Einstein in California, May-June, 1979

American Museum of Natural History, Peace and War, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

Mashable, Albert Einstein is important to 'Oppenheimer,' but not for the reason you'd think, July 21, 2023

New York Review of Books, On Albert Einstein, March 17, 1966

GameRant, Why Is Albert Einstein In Christopher Nolan's Oppenheimer?, July 14, 2023

Esquire, Did Oppenheimer Really Meet Einstein?, July 25, 2023

SFGate, The real relationship between Oppenheimer and Albert Einstein, Aug. 1, 2023

Inference, More Secrets, June 2021

Los Alamos National Laboratory, In the matter of J. Robert Oppenheimer, July 19, 2023

Interview, Thom Mason, director, Los Alamos National Laboratory, Aug. 18, 2023