Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

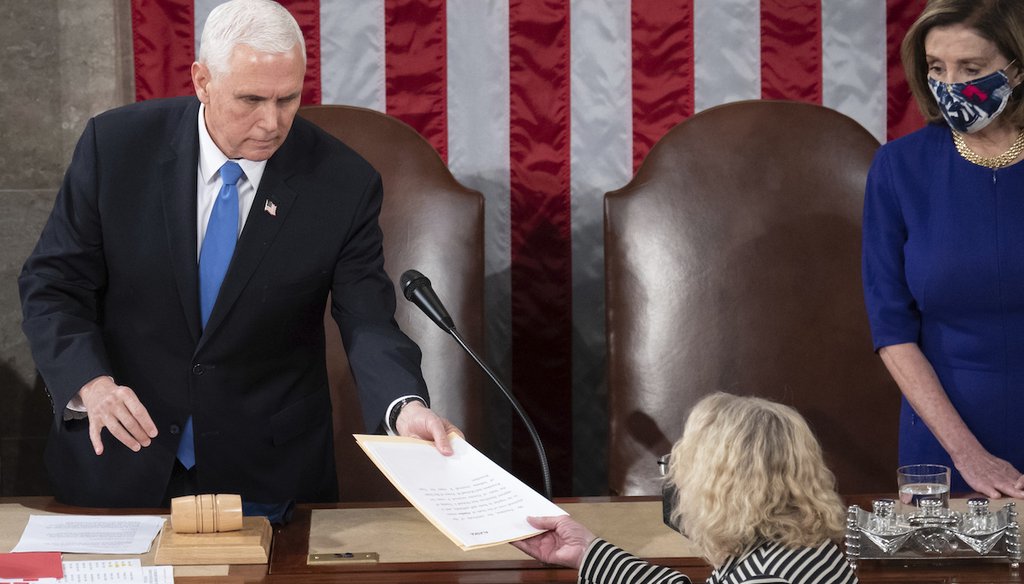

Vice President Mike Pence handles the electoral certificate from the state of Arizona at the joint session of Congress on Jan. 6, 2021. (AP)

If Your Time is short

• Both chambers of Congress have introduced legislation to update the 135-year-old Electoral Count Act, the murkiness of which supporters of then-President Donald Trump exploited on Jan. 6, 2021.

• The Senate and House bills are broadly similar, making clear that the vice president’s role in counting electoral votes is ceremonial. The bills also say that “alternative electors” that do not follow the proper procedures aren’t acceptable, and raise the number of lawmakers needed to object to a state’s electoral votes.

• The chambers would have to negotiate an identical version if an update to the 1887 law is to be enacted.

One of the major legislative efforts to prevent another insurrection like the one on Jan. 6, 2021, is moving a step closer to enactment.

Both chambers of Congress have introduced legislation to update the 135-year-old Electoral Count Act, which supporters of then-President Donald Trump exploited for its murkiness. Trump and his allies sought to convince then-Vice President Mike Pence to set aside some of the electoral votes cast for Joe Biden, in the hope that Trump would remain president.

Pence refused to do so, and Biden was sworn in two weeks later. Legal experts have urged revisions to the 1887 law to prevent this scenario from recurring.

In July, a bipartisan group of senators introduced the Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act of 2022 to clarify aspects of the 1887 law.

On Sept. 19, Reps. Zoe Lofgren, D-Calif., and Liz Cheney, R-Wyo., introduced the Presidential Election Reform Act, which overlaps in significant ways with the Senate bill but has some differences. Both Lofgren and Cheney are on the House committee investigating the events of Jan. 6.

"Our proposal is intended to preserve the rule of law for all future presidential elections by ensuring that self-interested politicians cannot steal from the people the guarantee that our government derives its power from the consent of the governed," Cheney and Lofgren wrote in a Sept. 18 op-ed in The Wall Street Journal.

House leaders have signaled a rapid timetable for considering the Lofgren-Cheney bill, probably within days of its introduction. With only a simple majority needed in the House, the bill is expected to pass with all Democratic votes and likely some Republican support.

House leaders have not given any indication yet that they would consider an earlier bill, sponsored by Reps. Josh Gottheimer, D-N.J., and Fred Upton, R-Mich., that mirrors the Senate measure.

The Senate bill, which is scheduled to be taken up in committee for possible amendments before the end of September, has 10 Republicans as official sponsors or cosponsors, and additional Republican senators have signaled a willingness to support the measure. If that support holds, then the Senate bill should have at least the necessary 60 votes to overcome a filibuster, all but ensuring passage.

It’s unclear when the Senate would vote on its version of the bill; it could be between the November election and the swearing in of the new Senate in January.

If both chambers pass differing versions of the measure, they’d need to be reconciled into identical legislation, likely through negotiations between Senate and House leaders.

Also unclear is the fate of a related Senate bill called the Enhanced Election Security and Protection Act. This measure would stiffen penalties for people who threaten election administrators; would seek to improve the handling of mail ballots; and would try to bolster security for election systems.

So far, four Republicans have signed on to co-sponsor this measure, but that would not be enough to overcome a filibuster.

Here’s a summary of both leading bills to overhaul the Electoral Count Act, along with commentary by legal experts about how they differ.

What’s in the Senate bill?

It clarifies and limits the role of the vice president. Normally, when Congress certifies the Electoral College vote, clerks unseal the results sent by each state, the vice president reads the results aloud, and the process moves on.

In 2021, Trump’s hopes for a do-over hinged on the presumption that the vice president has the authority to set aside the results from any given state, if there are reasons to question them. Although most legal experts agreed that this was a misreading of the 1887 law, the Senate bill would shut the door on that interpretation.

Not only does the bill say the vice president’s role is strictly "ministerial" — that is, merely ceremonial — it specifically lists what the vice president cannot do.

"The President of the Senate (the vice president) shall have no power to solely determine, accept, reject, or otherwise adjudicate or resolve disputes over the proper list of electors," the bill says.

It shuts the door on "alternative" slates of electors. Part of Trump’s plan was to send Congress "alternative" slates of electors who backed him, rather than the actual winner, Biden. The plan was to create enough confusion to give Pence the opening to reject the official results.

The Senate bill largely binds Congress to accept a single slate from each state. Once the state sends a fully certified slate, the bill says it must be "treated as conclusive." However, it allows a court to supersede that certification if the slate has been chosen contrary to the law.

It clarifies the way states must certify their electoral votes. The 1887 law fails to say who at the state level — typically, the governor or the secretary of state — has final say over certifying the slate of electors. In theory, this leaves open the possibility of a governor certifying one slate, and the secretary of state another.

The bill lets states decide who does the certification, but once a choice is made, it can’t be changed after the election.

It closes the "failed" election loophole. A law older than the Electoral Count Act, the 1845 Presidential Election Day Act, not only sets Election Day as the Tuesday after the first Monday in November, but it also has a section about what states should do if they have "failed to make a choice" on that day.

"The electors may be appointed on a subsequent day in such a manner as the legislature of such State may direct," the law says.

The problem is that the law doesn’t define a "failed" election. The Senate bill says that only "extraordinary and catastrophic" events would be grounds for declaring a failed election.

It raises the bar for congressional challenges. Right now, all it takes is one senator and one representative to challenge election results from a given state. That has made it easy for both Republicans and Democrats to raise issues in recent elections. The bill would raise the threshold to one-fifth (20%) of each chamber.

How does the Lofgren-Cheney bill compare with the Senate bill?

The bills have the same goals: to prevent a repeat of what Trump and his allies did on Jan. 6, when they exploited uncertainties in the law. But the specifics on how that would be achieved varies in some cases.

• Both would define the vice president’s role as ceremonial.

• Both would clarify that states cannot send competing slates of electors to Congress.

• Both say the law on choosing electors needs to be set before Election Day and can’t be changed afterward.

• Both would raise the threshold for lawmakers to object to a slate of electors. But the House bill would raise it even higher than the Senate would, to one-third of each chamber. The House bill would also more explicitly describe what is considered an acceptable objection.

• Both would close the "failed election" loophole, but in different ways. The Senate bill cites "extraordinary and catastrophic" as grounds for declaring a failed election. The House bill offers greater specificity about what circumstances can trigger a failed election: a natural disaster or terrorism. Only a presidential campaign could sue in federal court to seek extended voting under these circumstances.

Legal analysts identified a few other differences between the bills.

One has to do with the timeline for states to finalize their electoral votes; the House delays key dates, perhaps to allow more time for any challenges to play out before reaching Congress, said Michael Thorning, director of structural democracy at the Bipartisan Policy Center think tank.

Another difference is that the House bill would permit financial sanctions on election-related lawsuits that are not filed in good faith, and would permit lawsuits against officials who interfere with the process of certifying results.

The House bill also sets out a new process for counting the electoral votes, whereas the Senate makes a few important tweaks to the 1887 law.

Thorning said it’s potentially risky for the House to pass something different from a Senate bill that has effectively cleared a filibuster, because reconciling a final bill will require greater interchamber cooperation before enactment. Nevertheless, he said he could envision Senate support for tweaks based on the House bill.

"I don’t think the introduction of the House bill does any damage — it’s a different approach to resolving the same concerns," Thorning said.

Our Sources

Electoral Count Reform and Presidential Transition Improvement Act of 2022

Presidential Election Reform Act

Enhanced Election Security and Protection Act

Liz Cheney and Zoe Lofgren, "We Have a Bill to Help Prevent Another Jan. 6 Attack," Sept. 18, 2022

Congressional Research Service, "The Electoral College: A 2020 Presidential Election Timeline," October 22, 2020

Politico, "Seeing double: dueling electoral count overhauls," Sept. 20, 2022

CNN, "House lawmakers lay out proposal for legislation to prevent another January 6," Sept. 19, 2022

Washington Post, "House to move quickly on Electoral Count Act bill. When will Trump weigh in?" Sept. 20, 2022

NBC News, "House eyes vote on a new bipartisan bill to prevent another Jan. 6," Sept. 19, 2022

The Hill, "This week: Lofgren and Cheney to introduce Electoral Count Act reform," Sept. 19, 2022

PolitiFact, "Bipartisan bill aims to close the legal gaps in the Electoral Count Act Trump used to disrupt Jan. 6," July 21, 2022

Email interview with Richard H. Pildes, law professor at New York University, Sept. 19, 2022

Email interview with Edward B. Foley, law professor at Ohio State University, Sept. 19, 2022

Email interview with Richard L. Hasen, law professor at UCLA, Sept. 19, 2022

Interview with Michael Thorning, director of structural democracy at the Bipartisan Policy Center, Sept. 19, 2022