Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

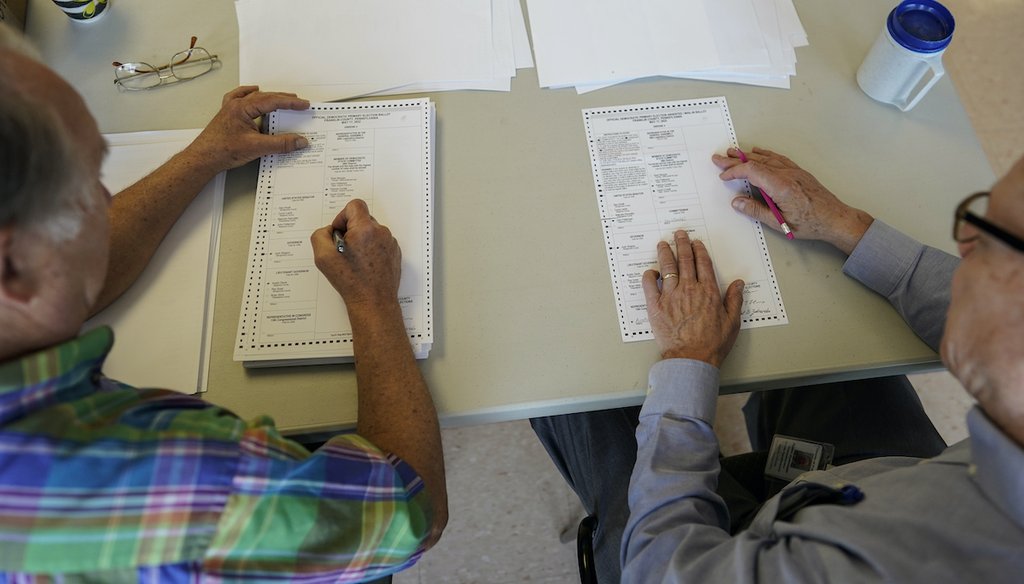

Democratic Franklin County Commissioner Bob Ziobrowski, right, and Republican Franklin County election board member Jerry Warnement, left, duplicate damaged absentee and mail-in ballots after the Pennsylvania election in Chambersburg on May 18, 2022.(AP)

During the midterms this year, more than 100 million Americans will likely vote. Voters who cast a ballot at an in-person site will witness only a small slice of what goes into operating elections. Millions of voters who fill out a mail ballot at their kitchen tables will see even less of the process.

We wanted to answer some common questions voters have about how elections operate. In a related story, we’ll also answer questions about how election workers reduce opportunities for fraud and deliver secure elections. Did we miss a question? Email us at [email protected].

Who runs elections? And how do we know they don’t fix the race for president?

Amid all the news about failed efforts in Congress to pass new national voting laws, you might think the federal government administers elections. It doesn’t.

Local government officials administer elections. They have many different titles: supervisor of elections, clerk, auditor or judge. They oversee counties, cities or townships. Overall, they follow state laws that set rules, such as when absentee ballots are mailed out and how long early voting lasts.

Local officials maintain voter registration lists, train poll workers, test equipment, mail out absentee ballots and run in-person voting sites. After the polls close, they are in charge of tabulating an initial, unofficial count. Many election officials also conduct post-election audits.

There are more than 10,000 local election jurisdictions across the country. This is part of how we know the presidential election wasn’t "rigged" for Joe Biden in 2020. It would take a massive scheme involving thousands of election workers — in the presence of the public, other election workers and independent observers — to pull off such a felonious heist across multiple states. That did not happen.

More than a year after the presidential election, the evidence has only grown that there was a secure election in 2020. After examining results for more than a year, the Associated Press found in December 2021 that fewer than 475 potential voter fraud cases existed in six battleground states: Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin.

If I vote by mail, how will I know my vote will be counted?

It’s a myth that mail ballots are only counted if an election is close. In fact, they are often counted first, usually once the polls close.

Many election offices offer ways for voters to track their own mail ballots, typically by entering basic information on a website or signing up to receive updates via text, email or phone call. BallotTrax is one example a tracking service that is used in multiple states.

If a mail ballot is rejected, often for missing the signature on an envelope or for a signature mismatch, voters are notified through ballot-tracking communications from local election offices. States have laws about the process and timeline for fixing the errors, or what election officials call "curing" a ballot.

If I’m a Democrat voting in a Republican area, or if I’m a Republican voting in a Democrat area, how do I know the election workers aren’t going to try to toss my vote?

Election workers take an oath to uphold the law and to administer elections fairly and accurately.

It’s common for election officials to work in bipartisan teams for various aspects of handling ballots. For example, Hamilton County, Ohio, elections officials work in bipartisan teams when they pick up ballots from drop boxes or at post offices. They do the same thing to verify ID information on mail ballots when scanning them into the county’s system.

Similar efforts to work in bipartisan teams exist for in-person voting and tasks such as recounts. For example, Florida law says that the county supervisor of elections shall appoint election boards of poll workers at each precinct and that "no election board shall be composed solely of members of one political party." (There is an exception if only candidates from one party appear on the ballot.)

In every election cycle, some voters send back a ballot that is torn, stained by spilled food or drinks, or has stray marks. All these mishaps damage a ballot so it can’t be fed into a scanner, so election officials often work in bipartisan teams to duplicate the ballot.

How do election officials make sure the count is accurate?

Local election officials take multiple steps to make sure results are reported accurately, as required by state laws. Here is an example of some of those steps as outlined by the Hillsborough County, Florida, Supervisor of Elections:

-

The county holds a public meeting weeks before Election Day to test election equipment, ensuring it lists every race and counts totals accurately. This is called logic and accuracy testing.

-

High-speed scanners used to tabulate results are stored under surveillance, and the equipment is sealed.

-

High-speed scanners will tabulate absentee ballots and store the results on a standalone server that is not connected to the internet or other networks. Early voting results are uploaded to a server the day before Election Day.

-

Tabulated results are stored in three spots: a storage drive in the machines, on a results tape printed from the machine and on paper ballots. Before the county certifies the official results, officials compare results to make sure they match.

-

The county conducts a post-election audit of results.

Tammy Patrick, a former Maricopa County election official and expert on elections at the Democracy Fund, said the steps Hillsborough takes are representative nationally, although not all states require all these steps.

What is a poll watcher (sometimes called an election challenger)? How are they different from poll workers?

Poll workers are temporary or permanent workers hired by a local election office and who handle tasks such as checking in voters, handing them ballots and ensuring that equipment remains in operation. Their boss is ultimately a township, city or county government official.

Poll watchers, or in some states "election challengers," have a different role than poll workers. Poll watchers are not government employees. They are usually chosen by political parties, candidates or on behalf of groups supporting or opposing a question on a ballot. The eligibility criteria and tasks for poll watchers or election challengers vary according to state laws, but generally, they are present to observe election administration, ask questions or report any problems to election officials. Some can challenge the eligibility of a voter to cast a ballot.

The poll watchers usually must follow predefined steps for challenging a ballot. It is a crime to intimidate voters or interfere with the voting process.

Why does it take some states so many days to finish counting the votes?

If you hear results on election night, those are projected results based on unofficial counts. States set laws that give election officials time well beyond election night – often several days or longer – to report final, official results.

The initial leading candidate at any time on election night may not end up being the winner if the count is close and there are a lot of mail ballots. If that happens, it’s not a sign of fraud – it’s a sign of how the normal ballot-counting process works.

The time it takes to count mail ballots varies a lot by state. Some states allow mail ballots to be counted before Election Day, but others do not. Other steps that slow down the process can include comparing signatures to verify the voter’s identity and opening envelopes to access the ballots.

Each state sets its own deadlines for when mail ballots must be received. Thirty-one states require mail ballots to be received on or before Election Day while 18 states and the District of Columbia will accept and count a mail ballot if it is postmarked on or before Election Day. States also set their own deadlines and processes for counting provisional ballots and recounts.

Voters can help streamline the ballot-counting process by not waiting until the last minute to return their ballots, Matthew Weil, director of the elections project at the Bipartisan Policy Center previously told PolitiFact. "When I talk to voters, I tell them to do it earlier in the process, so we don’t have to overwhelm the system."

RELATED: All of our fact-checks about elections

RELATED: What can the federal government do right now to protect voting rights before the 2022 midterms?

RELATED: Much has changed since Jimmy Carter’s report on fraud in mail voting

Our Sources

National Conference of State Legislatures, Election resources, Jan. 5, 2022

Brennan Center, 2020’s Lessons for Election Security, Dec. 16, 2020

NPR, Voting Security Has Come A Long Way Since 2016 — But Vulnerabilities Remain, Nov. 3, 2020

The Conversation, Articles on Voting security, 2016-2019

Election infrastructure initiative, New Report Finds That More Than $50 Billion is Needed to Modernize and Run State and Local Elections Infrastructure, Dec. 14, 2021

U.S. Election Assistance Commission, Election security preparedness

VoteBeat, How election administrators can protect elections by speaking up, Nov. 22, 2021

Scientific American, An Expert on Voting Machines Explains How They Work, Nov. 3, 2020

NBC, 'Online and vulnerable': Experts find nearly three dozen U.S. voting systems connected to internet, Jan. 10, 2020

New York Times, The Myth of the Hacker-Proof Voting Machine, Feb. 21, 2018

Politico, ‘Reckless and stupid’: Security world feuds over how to ban wireless gear in voting machines, Feb. 9, 2021

Election Assistance Commission, Press release about new voluntary voting system guidelines, Feb. 10, 2021

Reuters, Trump allies breach U.S. voting systems in search of 2020 fraud ‘evidence’ April 28, 2022

AP, Far too little vote fraud to tip election to Trump, AP finds, Dec. 14, 2021

BallotTrax, Where's My Ballot? Accessed May 9, 2022

Reno Gazette Journal, 3 ways to mess up your mail-in ballot in Washoe County — and how to fix a mistake, April 27, 2022

Douglas Jones, computer science professor at the University of Iowa in Washington Post, Five myths about voting machines, Dec. 24, 2020

Washington Post, The Cybersecurity 202: More states now have paper trails to verify votes were correctly counted, Nov. 5, 2020

Atlanta Journal-Constitution, U.S. cybersecurity agency reviews hacking risk to Georgia voting system, Feb. 11, 2022

8 News Now, Nevada man who voted twice using dead wife’s ballot sentenced to probation, fined $2,000, Nov. 16, 2021

Hamilton County, Ohio, Video about absentee ballots, Oct. 22, 2021

Electronic Registration Information Center, Website, Accessed May 9, 2022

U.S. District Court for Northern District of Georgia, Donna Curling vs Brad Raffensperger, CISA status report update, April 18, 2022

Washington Post, Hackers were told to break into U.S. voting machines. They didn’t have much trouble. Aug. 12, 2019

PolitiFact, What can the federal government do right now to protect voting rights before the 2022 midterms? Feb. 18, 2022

PolitiFact, Ballot drop boxes have long been used without controversy. Then Trump got involved, Oct. 16, 2020

PolitiFact, The faulty premise of the ‘2,000 mules’ trailer about voting by mail in the 2020 election, May 4, 2022

Email interview, Gerri Kramer, spokesperson for the Hillsborough County Supervisor of Elections (Florida), May 10, 2022

Email interview, Tammy Patrick, a former Maricopa County elections official and expert on elections at the Democracy Fund, May 10, 2022