Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

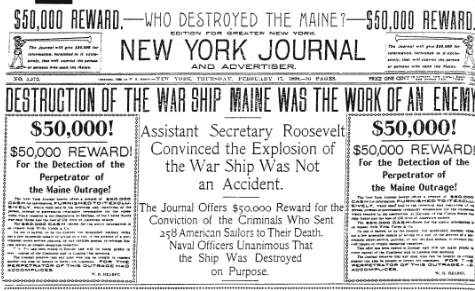

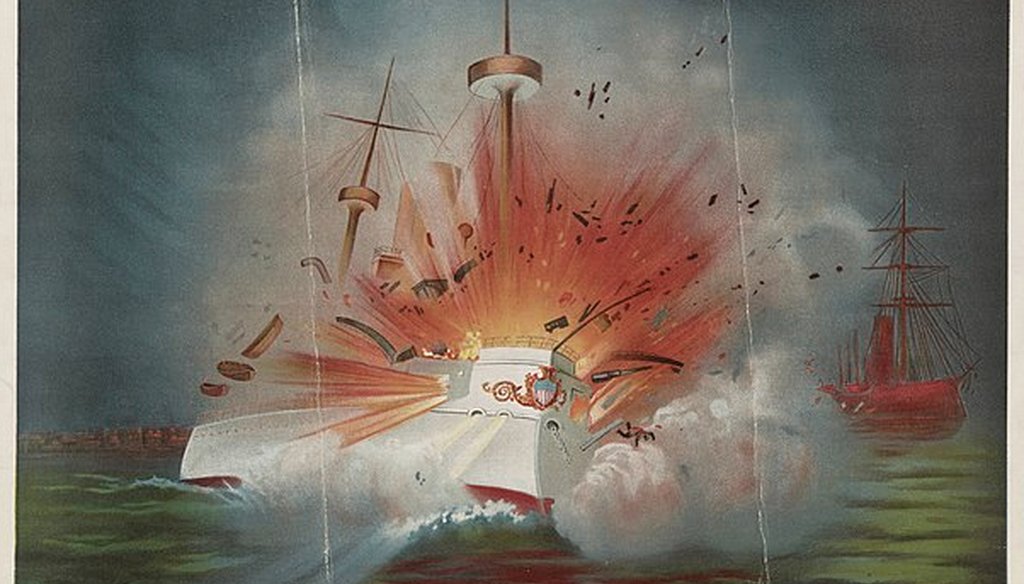

Print showing the explosion of the U.S.S. Maine in 1898. (Library of Congress)

Scroll through social media feeds today and you can expect to be bombarded with dubious claims about Russia’s war in Ukraine. Many were created by or on behalf of Russia, either to cast doubt on atrocities or to condemn Ukraine and its leaders for things they didn’t do.

Fact-checkers like PolitiFact work to determine the truth of such claims, as journalists on the ground risk their lives to root out the truth and combat misinformation.

The internet and social media are relatively new developments, but the media, in one form or another, have long played a role in communicating what is happening on overseas battlefields. And their role has not always been a constructive one.

A new exhibit at Tampa’s Henry B. Plant Museum looks back at what role so-called "yellow journalism" may have had in pushing the United States into war against Spain in 1898.

"Stop the Presses! Fake News and the War of 1898" focuses on the late 1890s, when newspaper moguls William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer used exaggerated and emotionally charged coverage to sell their papers in New York City. The period was characterized by the famous, and almost certainly apocryphal, remark by Hearst: "You furnish the pictures. I’ll furnish the war."

The exhibit aims to demonstrate "how false or misleading information can disrupt, or even dismantle, democratic society, especially during times of crisis." It also addresses the roles played by contemporary small-town and rural newspapers, the Black press, and other media, not all of which were as eager to see a war in Cuba as Hearst and Pulitzer were.

Given the brutal war raging in Ukraine — and the online struggle for accurate information — we reached out to several historians of the era to gauge the differences and similarities in the media environments of 1898 and today.

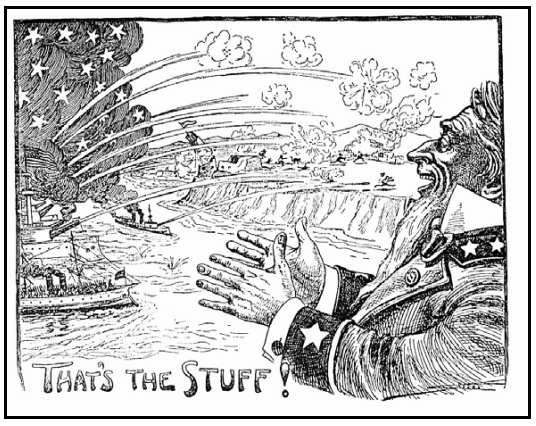

Coverage of the sinking of the USS Maine in the New York Journal, 1898. (Wikimedia Commons)

The road to war in 1898

"Yellow journalism" got its name from the Yellow Kid, a popular cartoon character drawn by Richard F. Outcault whose strip became subject of a bidding war between Hearst and Pulitzer, the two New York City newspaper titans who were constantly in a war for readers.

"Once the term had been coined, it extended to the sensationalist style employed by the two publishers in their profit-driven coverage of world events, particularly developments in Cuba," a State Department historical page says.

One of the main topics of this newspaper coverage was the deteriorating humanitarian situation in Cuba. Spain was the colonial power in Cuba, but its grip on the empire was weakened, and to regain control, officials ordered harsh policies on the local population, including a "reconcentration" policy that has been described as an early version of concentration camps.

The U.S. government watched the situation closely and tried to work out a diplomatic solution, but events began to spiral after a U.S. military ship docked in Havana harbor exploded in February 1898 and sank, killing 261. It was unclear whether the sinking of the USS.Maine was an accident or sabotage, but Pulitzer’s New York World and Hearst’s New York Journal were unafraid to report the wildest rumors of what sank the Maine.

The newspapers’ reporting created a pro-war environment, and by early May 1898, the U.S. entered what became known as the Spanish-American War.

Why did the sinking of the Maine inspire exaggerated coverage?

What happened to the ship was a genuine mystery, which allowed speculation to run wild.

"Official investigations have been conducted multiple times over the last 100 years and they have arrived at different conclusions," said Paul McCartney, a Towson University political scientist who has written extensively about the era. "This indicates the inherent ambiguity of the evidence."

The lack of consensus about what actually happened continues to the present day.

"Even after all these years, the cause of the Maine’s sinking remains disputed," said W. Joseph Campbell, a professor of communications at American University and author of "Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies."

In addition, there were a range of possible perpetrators. Although Spain had little reason to attack the U.S. directly, "it is certainly possible that a rogue Spanish official committed the act," said Bonnie Miller, a historian at the University of Massachusetts-Boston and author of "From Liberation to Conquest: The Visual and Popular Cultures of the Spanish-American War of 1898." "Or it could also have been a Cuban insurrectionist who was eager to compel the U.S. to intervene militarily."

"We may never know," Miller said.

It was almost inevitable that the papers owned by Hearst and Pulitzer would publish articles that pushed speculation and unproven theories. Though they lacked direct evidence, the newspapers deployed "rhetorical strategies" to convince Americans of a Spanish attack, Miller said.

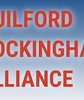

"They quoted from experts offering opinions by looking at photographs, they included vivid illustrations of the wreckage and offered theories about how the explosion occurred, and they sentimentalized the narrative of going into the war as a morally righteous fight in political cartoons and other visual media," Miller said.

Concerns about "fake" coverage had already been circulating for several years. In 1897, a journalist named George Bronson Rea published a book titled, "Facts and Fakes About Cuba."

"The point is, this concept — complaints about media content and conduct — goes way back," Campbell said.

Cartoon from the Denver Post, June 7, 1898. (Public domain)

What impact did ‘yellow journalism’ have in pushing the United States to war?

While there’s general agreement that the yellow journalism era was a low point for cautious, ethical journalism, there’s also widespread agreement that it did not push the United States into the war on its own.

The media simply "didn’t have that kind of agenda-setting power," Campbell said. There’s little if any evidence of the newspaper war actually moving policymakers like President William McKinley, he said.

"If the content of the yellow press had an influence on McKinley, you would see the evidence in the private diaries and letters of officials," Campbell said. "But the available record is more likely to include mentions of how complicating the press’ role was. The record does not indicate that the press was setting the policy direction. It wasn’t treated with any seriousness."

It’s also not at all clear that newspapers elsewhere were following the aggressive stance of the World and the Journal, which were mostly read by New Yorkers.

Perhaps the most persuasive argument that the yellow press didn’t drag the U.S. into war was that the humanitarian situation in Cuba was dire — so dire that it inspired a strong response among Americans even without the media’s goading. "The yellow press did not cause the deaths in the reconcentration areas," Campbell said. "It got an awful lot of attention, not just from the yellow press but from other papers as well."

The American people were "pretty pro-interventionist at that moment, and it would have been hard for a president to toe the peace line after the Maine went down," McCartney said. "The media's role in the coverage of the sinking of the Maine had little to do with this sentiment, which was already firmly in place."

Louis A. Pérez Jr., a historian at the University of North Carolina, suggested that the role of the media in 1898 was akin to its role during the run-up to the Iraq War in 2003, when mainstream media outlets were criticized, especially in retrospect, for being too willing to take government claims at face value.

In 1898, newspapers were "disseminating a political rationale in the service of the national interest," Pérez said. "The policy was already set in motion, and the press basically fell in line."

What does 1898 tell us about coverage of conflicts today?

In both Cuba in 1898 and Ukraine in 2022, "the media played the central role in shaping the understanding of a public that otherwise has not previously had much occasion to learn the intricacies of the situation," McCartney said. Media outlets may be tempted to offer "simple narratives and superficial analyses."

In addition, the press in both periods was heavily partisan. "So media consumers got narratives that emphasized some aspects of the events more than others, depending on the message they wanted to get across," McCartney said.

Still, the comparisons between 1898 and 2022 are far from exact.

In the case of the Maine’s sinking, the uncertainty stemmed from a shortage of verifiable information. What the yellow press published "wasn’t misinformation in the sense that they were lying about a known fact," said Cornell University historian David Silbey. Instead, he said, "it was pushing what was known much farther than it should have gone."

By contrast, much of today’s misinformation, including Russian propaganda efforts, is designed to cast doubt on verifiable facts and foster conspiracy theories.

Another difference, Miller said, is that in 1898, the coverage framed Spain as a whole as the enemy, employing "anti-Catholic imagery and ideology to argue for the inherent depravity of the Spanish people." Today, most mainstream media coverage focuses on Russian President Vladimir Putin as the driving force behind Russia’s invasion.

"Today, many Americans recognize that the Russian people are not the cause of this invasion — that they themselves are being duped by Putin’s misinformation campaigns," Miller said.

Finally, social media may now be at least as important as traditional media, if not more so.

"The existence of social media allows this kind of information to get out there, instantaneously, which was not possible in the same way in 1898," McCartney said. "Social media users also have ideological preferences and agendas, unmoored by professional ethics" or an obligation to tell the whole story.

The Poynter Institute is a partner for the Henry B. Plant Museum exhibit and is hosting a discussion on April 29, beginning at 5:30 p.m. The event is titled, "The History of Fake News: From the War of 1898 to the 2022 Russian Invasion of Ukraine." The museum exhibit runs through December.

Our Sources

Henry B. Plant Museum, "Stop the Presses! Fake News and the War of 1898," accessed April 26, 2022

State Department Office of the Historian, "U.S. Diplomacy and Yellow Journalism, 1895–1898," accessed April 26, 2022

Email interview with Paul McCartney, Towson University political scientist, April 26, 2022

Email interview with David Silbey, Cornell University historian, April 25, 2022

Email interview with Bonnie Miller, historian at the University of Massachusetts-Boston and author of "From Liberation to Conquest: The Visual and Popular Cultures of the Spanish-American War of 1898," April 26, 2022

Interview with Louis A. Pérez Jr., historian at the University of North Carolina, April 25, 2022

Interview with W. Joseph Campbell, professor of communications at American University and author of "Yellow Journalism: Puncturing the Myths, Defining the Legacies," April 25, 2022