Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

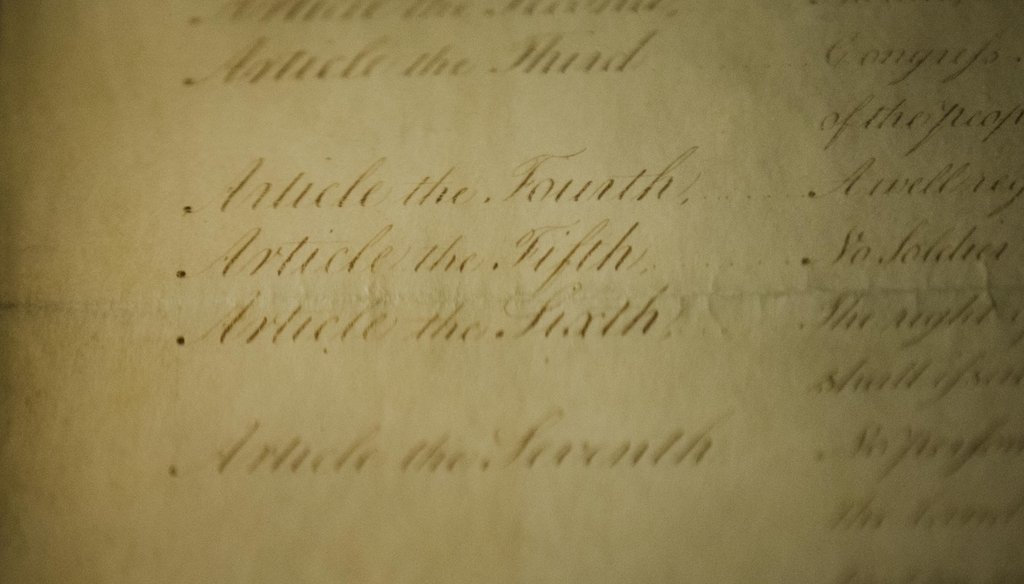

A portion of a rare, original copy of the Bill of Rights. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

The U.S. Constitution’s 22nd Amendment says, “No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice.”

-

Legal scholars said the use of the word “elected” leaves open the question of whether a person can “serve” as president without being elected to that office a third time. A motivated president could seek to exploit that interpretation but would face legal hurdles.

-

Experts said that whatever constitutional interpretation could make a third Donald Trump presidential term possible, it would violate the 22nd Amendment’s clear intent.

Several times since he’s returned to the White House, President Donald Trump has teased the possibility of serving more than two terms in office.

In an interview with NBC’s Kristen Welker that aired March 30, Welker asked Trump, "Have you been presented with any potential plans that would allow you to serve a third term?"

Trump responded, "Well, there are plans. … There are methods which you could do it, as you know."

Welker asked whether this included the possibility of Vice President JD Vance, or another ally, running for president with Trump as his vice presidential nominee in 2028, and then, if the ticket wins, Vance stepping down and Trump ascending to the presidency.

Trump said, "That's one. But there are others too."

Trump, a Republican, declined to specify other scenarios, saying it’s "far too early to think about it." But Trump said that he was serious.

"I'm not joking," he said.

We asked constitutional law experts what they thought about Trump’s rationale for legally serving a third term.

They said the clear language of the Constitution’s 22nd Amendment directly bars Trump from running for a third term, and they widely agreed that allowing a president a third term would violate the Constitution’s spirit.

But would it violate its letter? It might not, legal experts said.

A scenario like the one involving Vance, several legal scholars said, could provide a loophole that a motivated candidate like Trump could exploit — although with some big ifs.

Trump would need to get buy-in from the courts and Congress, and the voters, who would have to weigh whether his performance during his second term and his health at 82 years on Inauguration Day 2029 — an age older than Joe Biden was as president — merited another four years in office.

"I think the best interpretation" of the constitutional language "is that Trump is ineligible to become president for a third term," said Ilya Somin, a George Mason University law professor. "However, the issue is not airtight."

When we asked the White House to elaborate on Trump’s comment to Welker, White House Communications Director Steven Cheung said in a statement, "Americans overwhelmingly approve and support President Trump and his America First policies. As the President said, it’s far too early to think about it and he is focused on undoing all the hurt Biden has caused and Making America Great Again."

Could Trump legally run for a third term?

Beginning with George Washington, who made a point of stepping down in 1797 after two terms in office, every president until Franklin Roosevelt in the 1940s served no more than two full elected terms. But this was a norm, not a written rule, and after the Great Depression and the start of World War II, Roosevelt successfully ran for a third term, and then a fourth.

After Roosevelt’s unprecedentedly long tenure, officials of both parties agreed to codify the two-term presidential limit. The 22nd Amendment cleared Congress on March 21, 1947, and was ratified on Feb. 27, 1951, a little less than six years after Roosevelt died in office.

The relevant part of the 22nd Amendment says: "No person shall be elected to the office of the President more than twice."

This much, legal experts say, seems ironclad: No two-time winner of a presidential election can run for president a third time.

But there’s a caveat that hinges on the 22nd Amendment’s specific phrasing: It uses the word "elected."

"There are ways to become president other than being elected president, and therein lies the problem," said Brian Kalt, a Michigan State University law professor who wrote about the question in the 2012 book, "Constitutional Cliffhangers."

The logic undergirding a Vance-Trump switcheroo is that Trump would have been elected vice president, not president, and he would become president by succession, not by election.

"The constitution doesn't expressly prohibit that," said Frank O. Bowman III, a University of Missouri law professor.

The earliest and clearest articulation of this argument came in a 1999 law review article by Scott E. Gant and Bruce G. Peabody, then a junior lawyer and a Ph.D. student, respectively. Reached for this article, Gant — now a lawyer in private practice — said he still believed in the article’s analysis.

"A twice-elected president can clearly serve as president again," he told PolitiFact. Gant, who has since argued before the U.S. Supreme Court and taught about this issue in a Georgetown University law school seminar, cautioned against assuming how the justices would rule in a hypothetical case. Still, he said, "I would expect they would agree with our conclusion."

In his book, Kalt wrote that presidential succession, distinct from presidential election, was a familiar concept to lawmakers as they were drafting the amendment.

"At the very moment that the 22nd Amendment was written in 1947, the incumbent president was Harry Truman, who had succeeded to the office and had not (yet) been elected in his own right," Kalt wrote. "At that time, every generation in living memory had featured unelected presidents."

The constitutionality of the Vance-Trump scenario is not a slam dunk. The main legal argument against it comes from the 12th Amendment. That amendment, ratified in 1804, says, "No person constitutionally ineligible to the office of President shall be eligible to that of Vice-President of the United States."

However, the 12th Amendment makes no distinction between being elected president and serving as president. If one uses the logic that the 22nd Amendment prohibits a two-term president from being elected to a third term — but does not prohibit a president from serving a third term — then a two-term president is "eligible" to serve as president a third time, which would make Trump eligible to run as Vance’s vice presidential running mate.

There’s at least one other scenario that Trump could pursue. The Constitution doesn’t bar a former two-term president from becoming House speaker. Becoming president this way would require the resignation of both the elected president and an elected vice president; if that happened, the House speaker would be next in line for the presidency. (By the Constitution, an aspiring two-term president wouldn’t need to win a seat in the House to be elected speaker, although historically, the House has always elected one of its members as speaker.)

How realistic are these scenarios?

None of this is to say Trump’s path to securing a third term would be easy.

Even if he’s popular enough and healthy enough to be a credible president in 2028, he’d have to lock in a commitment from Vance, or whoever is the Republican presidential nominee, to step down if elected

Trump would also need to get on the ballot in enough states to secure an Electoral College majority, something that many Democratic-leaning states would likely oppose.

"This would presumably trigger court challenges on the ground that he would not be constitutionally qualified to assume the office any more than, say, an 18-year-old would be," Bowman said. "Those challenges should be successful, but these are weird times, and by then an even larger number of Trump loyalists will be on the federal appellate courts."

Although the issues were somewhat different, the Supreme Court’s 9-0 2024 ruling in Trump v. Anderson could bolster Trump’s quest for a third term. In that case, Colorado sought to bar Trump from the 2024 ballot, arguing that his role in the Jan. 6, 2021, U.S. Capitol riots disqualified him under the 14th Amendment. The justices disagreed that he could be barred on those grounds.

Meanwhile, if Trump managed to win the vice presidency, Congress could refuse to certify the election results. This might be a moot point if Republicans win majorities in both the House and the Senate, and if the party was still closely aligned with Trump. But if Democrats won control, they could theoretically block Trump that way.

Whatever constitutional interpretations could make a third Trump term possible, experts said it would violate the 22nd Amendment’s clear intent.

"By any measure, the whole point of the (22nd) Amendment was to send presidents home after two terms, and it looks as though this is what Congress and the states thought they were doing," Kalt wrote.

Even if the courts and Congress lined up uniformly against a third Trump term, he would have another option, albeit unconstitutional by any measure: Simply refuse to give up the presidency.

"He'd have possession of the White House as well as at least nominal control over the national instruments of coercion, federal law enforcement and the military," Bowman said.

Our Sources

Transcript of Donald Trump-Kristen Welker interview, March 30, 2025

22nd Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, National Constitutional Center, accessed March 31, 2025

National Constitution Center, "The 22nd Amendment and Presidential Service Beyond Two Terms," Nov. 11, 2024

Bruce G. Peabody and Scott E. Gant, "The Twice and Future President: Constitutional Interstices and the Twenty-Second Amendment" (Minnesota Law Review), 1999

Oyez, Trump v. Anderson, 2024

Brian Kalt, "Constitutional Cliffhangers," 2012

Michael C. Dorf, "A Third Trump Term?" Nov. 13, 2024

Email interview with James Robenalt, partner at the law firm Thompson Hine LLP, March 31, 2025

Email interview with Michael Gerhardt, University of North Carolina law professor, March 31, 2025

Email interview with Kermit Roosevelt, University of Pennsylvania law professor, March 31, 2025

Email interview with Frank O. Bowman III, University of Missouri law professor, March 31, 2025

Email interview with Brian Kalt, Michigan State University law professor, March 31, 2025

Email interview with Ilya Somin, George Mason University law professor, March 31, 2025

Interview with Scott E. Gant, attorney, March 31, 2025

White House, statement to PolitiFact by Steven Cheung, March 31, 2025