Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

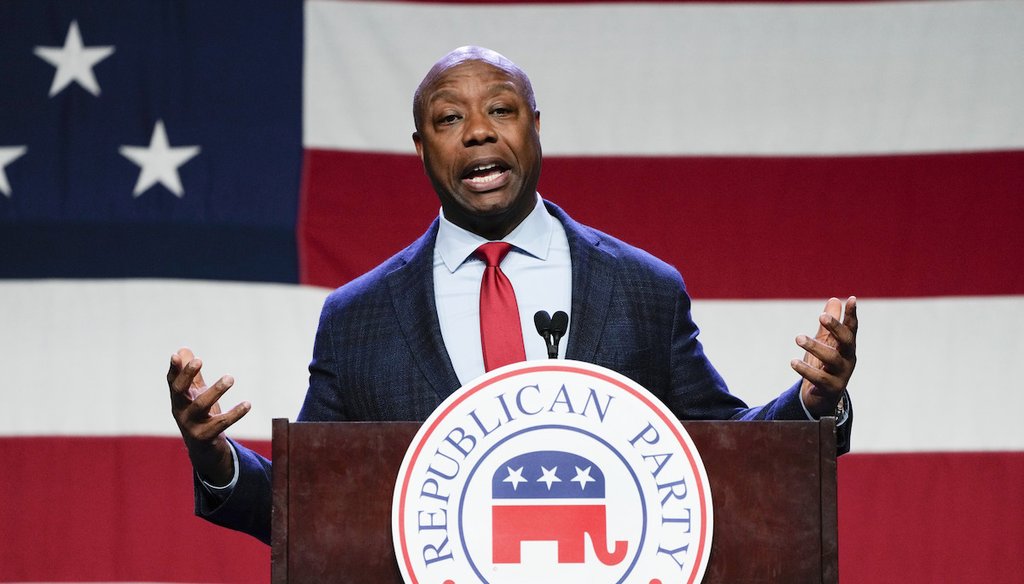

Republican presidential candidate Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., speaks at the Republican Party of Iowa's 2023 Lincoln Dinner in Des Moines, Iowa, July 28, 2023. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

Title 42, a public health policy that lets border officials quickly expel migrants from the U.S., can be used only to prevent a communicable disease from spreading. Fentanyl does not fall under this category.

-

Congress would need to pass a law to change the public health policy’s requirements or to codify similar restrictions in immigration law, but it would need at least 60 votes in the Senate.

-

Experts say Title 42 or Title 42-like restrictions would have little effect on fentanyl supply and overdose deaths because the drug is smuggled in mainly by U.S. citizens at official ports of entry. While Title 42 was in use, fentanyl seizures and overdose deaths continued to rise.

Republican presidential candidate Sen. Tim Scott has floated a plan he says will reduce the flow of fentanyl into the U.S.: reinstating the COVID-19 era public health policy known as Title 42.

Title 42, enacted by the Trump administration in March 2020 and lifted May 11, was used to curb the spread of COVID-19. It gave border officials the power to quickly expel people arriving at the southern border, essentially blocking their ability to apply for asylum.

"The current healthcare emergency we all know ain’t COVID, but it is fentanyl," Scott, of South Carolina, said Aug. 15 at the Iowa State Fair during a "fair-side chat" with Iowa’s Republican governor, Kim Reynolds. "We can reinstate something like Title 42 to stem the tide of 6 million illegal immigrants crossing our border. We can do that on Day 1 of my administration."

In his immigration plan released Aug. 6, Scott said that in his first 100 days as president, he would "make Congress pass the bill" he wrote codifying asylum restrictions similar to those in Title 42. The bill said that "in response to the fentanyl public health crisis," it would suspend people who are not legally allowed to enter the U.S. from entering the country via Mexico or Canada. Instead, they would be immediately expelled. Under immigration law, people must physically be in the U.S. to seek asylum, whether they entered legally or not. Scott introduced the bill, S. 1532, in May, but no actions have been taken since.

Scott has mentioned his plan in interviews and campaign events, proposing it as a means to solve the "current health care crisis" involving fentanyl, a synthetic opioid that is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine.

But policy experts say Scott can’t use the fentanyl crisis to restore Title 42. And even if he did seek to enact Title 42-style immigration restrictions, such measures would be unlikely to lower the amount of fentanyl coming into the country or the number of overdose deaths. That’s because although most illegally sourced fentanyl in the U.S. comes from Mexico, the drug is smuggled in mainly by U.S. citizens at official ports of entry.

A homeless person holds pieces of fentanyl in Los Angeles, Aug. 18, 2022. Use of the powerful synthetic opioid that is cheap to produce and is often sold as is or laced in other drugs, has exploded. (AP)

Why can’t the fentanyl crisis be used to reinstate Title 42?

Title 42 gives the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s director the power to stop foreign people or property from entering the U.S. to prevent the spread of a communicable disease. The U.S. code specifies examples of communicable diseases including cholera, smallpox and SARS — which COVID-19 falls under.

But fentanyl does not fall under this category as it is not a disease and cannot be transferred person to person, said David Bier, immigration studies director at the libertarian Cato Institute.

"Fentanyl does not meet those criteria, even if it is a public health crisis. It is not transmissible through contact, said Tony Payan, director of the Center for the United States and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. "It is something that is sold and consumed by the will of the individuals who do so."

This means that Scott would not be able to use the fentanyl crisis as the public health concern that would lead his administration to reinstate Title 42. If he did, "it would be challenged immediately," said Jeremy Slack, a University of Texas at El Paso professor and an expert in drug trafficking and the border.

Congress, however, could change the public health policy’s requirements or pass a law, like Scott’s proposed bill, giving the Department of Homeland Security powers similar to those under Title 42.

But passing such a law "would require hurdles that are not easy to pass," said Adam Isacson, defense oversight director at the Washington Office on Latin America, a research and human rights advocacy group. Those hurdles include getting past a 60-vote threshold in the Senate.

Why Title 42 or similar restrictions are unlikely to help the fentanyl crisis

Even if Congress did pass a law replicating Title 42 restrictions as Scott described, it likely would not reduce the amount of fentanyl entering the U.S. or lower the number of overdose deaths, experts said.

According to data from U.S. Customs and Border Protection, fentanyl seizures continued to increase after the Trump administration implemented Title 42, going from 257 pounds seized in February 2020 to 3,300 pounds in May 2023.

Synthetic drug overdose deaths, mostly fentanyl, also continued to rise during that time, from around 40,000 between April 2019 and March 2020 to around 72,000 from April 2022 to March 2023, CDC data shows.

"The idea that having an incredibly low rate of illegal immigration is going to somehow stop people from using hard drugs or using fentanyl is just really detached from reality," Bier said.

So why didn’t Title 42 lower fentanyl seizure and overdose numbers?

"Fentanyl is being trafficked by U.S. citizens and permanent residents through ports of entry," Slack said.

About 19,600 of the 22,000 pounds confiscated so far in fiscal year 2023 has been seized at ports of entry, according to CBP data. Last year, 88% of fentanyl arrests were of U.S. citizens who were not expelled from the U.S. under Title 42.

U.S. citizens and permanent residents are able to cross the southern border multiple times and know the territory better, said Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, an immigration expert at George Mason University.

Bier said even if all fentanyl were smuggled between ports of entry, Title 42 could actually have the opposite effect. Unlike under immigration law, people caught by Border Patrol and immediately expelled to Mexico via Title 42 do not face legal consequences, so they could drop the fentanyl they’re carrying into the bushes and try to enter the U.S. again after being expelled.

Our Sources

PolitiFact, Title 42 expiration: What's next for migrants applying for asylum at US’ southern border?, May 8, 2023

PolitiFact, Ask PolitiFact: Do rising fentanyl seizures at the border signal better detection or more drugs?, March 20, 2023

Vote Tim Scott, TIM SCOTT: SECURING THE BORDER, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

U.S. Senate, Alan Shao Jr. Fentanyl Public Health Emergency and Overdose Prevention Act, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

Vote Tim Scott, post, Aug. 13, 2023

National Institute on Drug Abuse, What is fentanyl?, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

RAND Corp., Commission on Combating Synthetic Opioid Trafficking, Feb. 2022

Legal Information Institute, 42 U.S. Code § 265 - Suspension of entries and imports from designated places to prevent spread of communicable diseases, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

U.S. Code, TITLE 42—THE PUBLIC HEALTH AND WELFARE, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

Sen. Tim Scott, Senator Scott Introduces Legislation to Extend Powers of Title 42 to Combat Fentanyl Crisis, May 10, 2023

National Center for Health Statistics, Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

U.S. Sentencing Commission, Quick Facts — Fentanyl Trafficking Offenses, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Drug Seizure Statistics FY2023, accessed Aug. 16, 2023

Email interview, Tony Payan, Director, Center for the United States and Mexico at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, Aug. 14, 2023

Email interview, Josiah Heyman, anthropology professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, Aug. 14, 2023

Email interview, Jeremy Slack, assistant professor at the University of Texas at El Paso, Aug. 14, 2023

Phone interview, Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, professor at George Mason University, Aug. 14, 2023

Phone interview, David Bier, immigration studies director at the Cato Institute, Aug. 15, 2023

Email exchange, Adam Isacson, defense oversight director at the Washington Office on Latin America, Aug. 15, 2023