Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

A police officer reacts as he walks in downtown Highland Park, Ill., a suburb of Chicago, July 4, 2022, where a mass shooting took place at a Fourth of July parade. (AP)

If Your Time is short

• Robert Crimo III confessed to the Highland Park shooting, law enforcement said, and has been charged with murdering seven people at the July 4 parade in Highland Park. But it wasn’t Crimo’s first brush with the law.

• Law enforcement in Illinois can file "red flag" orders against people they consider to pose a danger of causing injury to themselves or others. This was not done in Crimo's case.

• There may not have been enough public awareness of the red flag law at the time Crimo came into contact with police, said lawmakers, lawyers and doctors in Illinois. Recent legislation, both state and federal, includes money for public awareness campaigns and more training of police.

After mass shootings in Florida and Texas, Congress passed a bipartisan bill in June that includes money for states to implement "red flag" laws, a way for family members and law enforcement to ask courts to take away guns from people with patterns of violence.

Not even two weeks later, a man with a known pattern of concerning behavior shot dozens of people at an Independence Day parade in Illinois — a state that has had a red flag law on the books for over three years.

Robert Crimo III confessed to the shooting, law enforcement said, and has been charged with murdering seven people at the July 4 parade in Highland Park.

It wasn’t Crimo’s first brush with the law: Crimo had previously threatened to kill his family and had multiple knives seized from his home. But law enforcement and his family never initiated a red flag process that could have temporarily taken away his ability to own a firearm.

As the Highland Park shooting shows, merely having a red flag law on the books does not guarantee that it will be adequately used. PolitiFact and other outlets reported before the shooting that Illinois had rarely used the law.

Dr. Traci Kurtzer, a physician at Northwestern Medicine, teaches health care professionals and community members about the use of Illinois’ red flag law, known as the Firearms Restraining Order Act. (Red flag laws are also called extreme risk protection orders or gun violence restraining orders.)

Kurtzer told PolitiFact the law "has been very underutilized, mainly because so many are just not aware it exists, and that includes law enforcement officers."

When the law passed, there was no funding for education or public awareness campaigns, Kurtzer said. That may be why no one took action against Crimo before the shooting.

"It is heartbreaking to know this preventative step could have been done and possibly made a difference, " Kurtzer said.

Illinois state Rep. Denyse Stoneback, D-Skokie, recently passed a bill for a $1 million education campaign for police and the public about the state’s law. She told PolitiFact she believed it could have been used against the Highland Park shooter.

"It was a lack of implementation, for sure. The firearms restraining order law in Illinois was established to catch situations like these – where you have an individual who's having either mental health issues or a person in crisis, and they are a threat to themselves or others," she said.

"This person should not own or possess or be able to purchase firearms. And unfortunately, in this case, there were many missed opportunities for intervention and prevention of the tragedy that we saw unfold in Highland Park," she said.

What we know about the mass shooter’s previous contacts with law enforcement

Law enforcement agencies had several contacts with Crimo before the shooting.

In April 2019, there was a 911 call to police that Crimo had attempted suicide. Police spoke with his family, and the matter was handled by mental health professionals, said Lake County Major Crime Task Force spokesperson Chris Covelli.

In September 2019, Illinois State Police received a Clear and Present Danger report — an alert from local police to state police about a threatening person — on Crimo from the Highland Park Police Department. Crimo had allegedly threatened his family, and it led to police taking knives from his bedroom, according to the report and a July 5 statement from the state police.

When the police went to Crimo’s house, he denied that he was going to harm himself or anyone else, and his mother denied the threats against the family. His father said the knives were his and were being stored in his son’s closet "for safekeeping," leading the Highland Park Police to return them.

Crimo was not arrested, and state police said that the family was unwilling to move forward on a complaint, "nor did they subsequently provide information on threats or mental health that would have allowed law enforcement to take additional action."

Neither the family nor law enforcement filed a firearms restraining order or protection order and the state police considered the matter concluded.

That may be because the red flag law had just been passed the previous year and had become law only a few months earlier, on Jan. 1, 2019.

Stuart Reid, an attorney and the legislative liaison for People for a Safer Society, an Illinois nonprofit focused on gun violence prevention, said that he isn’t surprised that no one filed a firearms restraining order for Crimo.

"My office was working to get information out to the public about it, but there weren't even forms available on the websites for most counties in Illinois in the early summer of 2019. At that point, there had been essentially zero training whatsoever to law enforcement about it. There has still been very modest training to law enforcement about it in the state."

However, Reid said that the existence of the Clear and Present Danger report, which says that it identifies "persons who, if granted access to a firearm or firearm ammunition, pose an actual, imminent threat," should have motivated police to file a red flag case against Crimo.

"I think when you look at the language of their Clear and Present Danger form, they should have moved forward," he said.

If a red flag case had been made, it likely would not have still been in effect three years after Crimo made the threats, because a judge must renew the order every six months. But it could have convinced state police to deny him a Firearms Owners Identification card when he applied in December 2019.

How Crimo obtained weapons

When a Clear and Present Danger report was filed against Crimo in September 2019, he didn’t own guns and hadn’t applied to buy them. Local police filed the Clear and Present Danger report, but when state police reviewed it, the reviewing officer "concluded there was insufficient information for a Clear and Present Danger determination," according to a statement from state police after the shooting. So there would be no formal determination found later when Crimo applied to buy a weapon.

In December 2019, Crimo — then 19 — applied for a Firearm Owners Identification card, called a FOID card. Since he was under 21, his application was sponsored by his father. State police said that when they reviewed his application in January 2020, there was "no new information to establish a clear and present danger, no arrests, no prohibiting criminal records, no mental health prohibitors, no orders of protection, no other disqualifying prohibitors and no Firearms Restraining Order," so they didn’t deny the application.

Crimo passed four background checks when purchasing firearms, through the state’s Firearms Transaction Inquiry Program that includes the federal National Instant Criminal Background Check System. Those checks occurred between June 2020 and September 2021.

The only offense included in Crimo’s criminal history was an ordinance violation in January 2016 for possession of tobacco. State police had no mental health prohibitor reports submitted by health care facilities or personnel.

The red flag law in Illinois allows police or family members to petition the court

Although neither police nor his family filed a red flag case for Crimo, Illinois law outlines a roadmap for how the process would look if they had. In Crimo’s case, either his family or the police could have started the process.

Illinois' Firearms Restraining Order Act says both law enforcement and family members — including unmarried partners who share a home or child can petition the court to temporarily take away guns and a Firearm Owners ID card from someone.

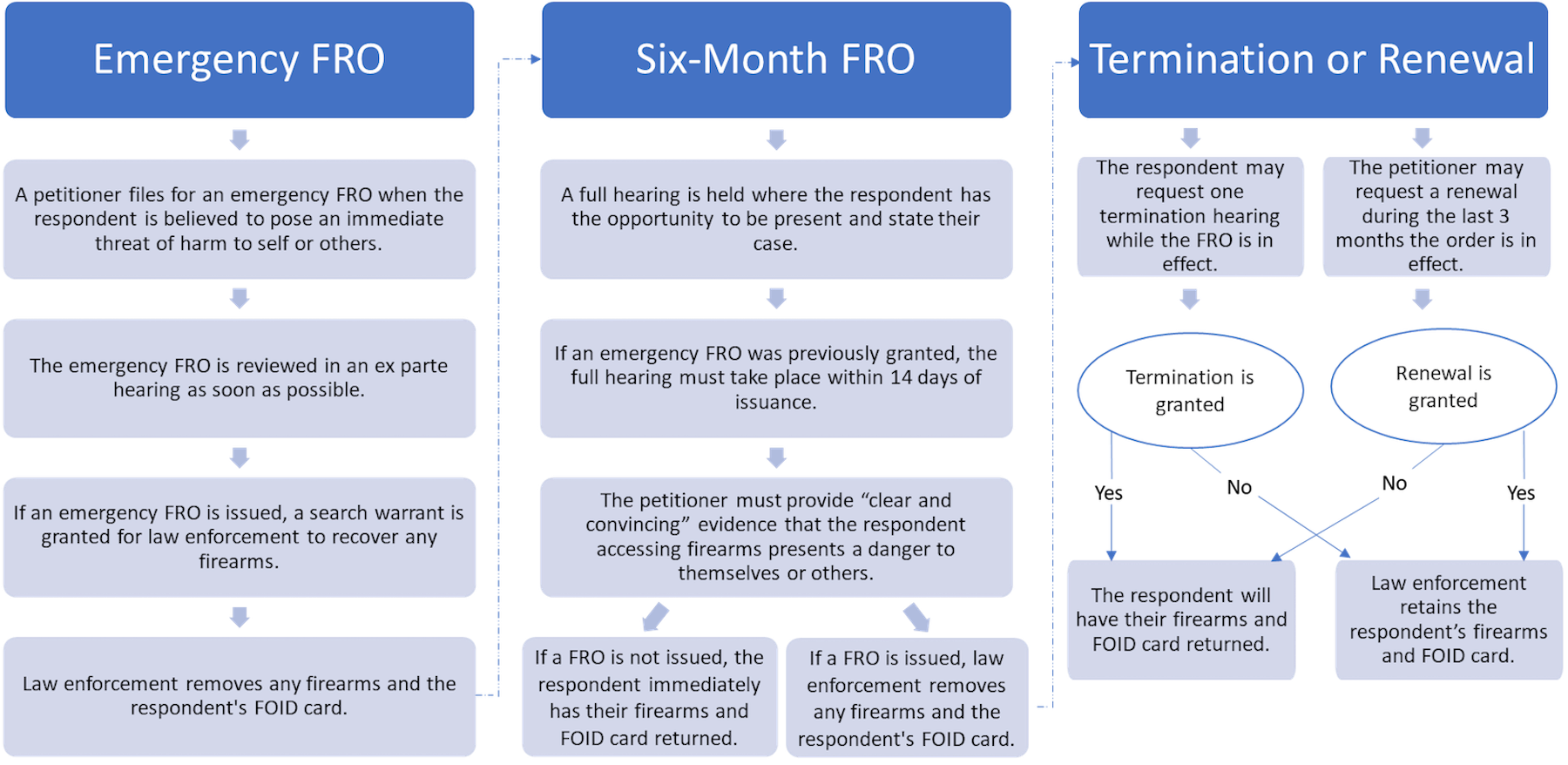

There are two types of petitions: an emergency restraining order that lasts only a few weeks and a longer, six-month order. To apply for either, members of the public or police must fill out two forms — a verified petition form and then a form to request removal. They can file them in the circuit court where the concerning person lives or in the county where they pose a threat.

On the form, the petitioner is asked to describe specifics of the person’s guns and their locations, and to notify family members of the petition. It also directs law enforcement to refer the person to counseling resources. It's not unusual for petitioners to leave blanks when they don’t know where the person’s guns are but feel confident that they are threatening.

If a family member or police officer fills out an emergency petition, a judge holds a hearing on the same or next day to determine whether the person meets the criteria of posing "an immediate and present danger" to others or themselves. This process is done "ex parte," meaning it’s done without notifying the person. However, within two weeks, a judge must schedule a full hearing — with civil court procedures, including the ability for the person to testify on their own behalf — if the restraining order is to be extended to six months.

For a six-month order, a person must pose "a significant danger of causing personal injury to himself, herself, or another in the near future" by having guns and ammunition. The court then schedules a hearing within 30 days of the petition (14 if it’s an extension of an emergency order) and considers the person’s history of violence, arrest records, abuse of substances and history of threats, along with other relevant factors.

If a judge agrees that the respondent poses a "significant danger," the judge signs a search warrant to seize all guns, gun parts and ammunition from the person — and to prevent them from owning or buying any for up to six months. At any point during those six months, respondents can submit one request to stop the restraining order if they can prove they present no danger. A petitioner can ask the court to renew an order during the last three months of an order.

In theory, Reid said, family members can file the form, but "in practice, it’s mostly been law enforcement agencies that brought them," although he emphasized the small number of cases. Kurtzer said that law enforcement can file a petition independently, without family confirmation or authorization, so long as they have proof of concern to show the judge.

Infographic from the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority

Can a little-used law be improved?

How often are red flag cases filed in Illinois? Speak for Safety Illinois, an advocacy group that tracks the cases, documented 34 cases filed in 2019 and 19 in 2020. Around half of these cases came from one county: DuPage, a county that includes some of Chicago’s suburbs. Other than Speak for Safety’s numbers, there’s little data about red flag cases.

"We don't even have enough data really to reach any conclusions about patterns, because there's not enough public information that's been made available about the law yet," said Reid, who practices in DuPage. However, education seems to be key.

"The DuPage County State's Attorney's Office is actively promoting this, doing the education, to their respective departments within DuPage County about how this law works, including the practicalities – teaching them the forms and the processes."

Eric Rinehart, the state attorney for Lake County, where Highland Park is located, called for Illinois to increase the use of the law.

"We need to make sure that law enforcement is using the red flag law, the firearm restraining order law," he told reporters.

Allison Anderman, senior counsel at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, said laws are only as good as their implementation.

"I do not think this teaches us anything about the limits of red flag laws other than the fact that people need to know about it and know how to use it," Anderman said. The funding in the recently passed federal law might help with that, she said.

Illinois Gov. J.B. Pritzker said following the shooting that all residents of Illinois should "learn about and use the Illinois Firearm Restraining Order Act already in law to alert authorities to dangerous individuals with guns." Pritzker said he will work with the General Assembly to strengthen gun control and red flag laws.

Representative Stoneback’s funding bill may provide a path forward. The expansion includes a training curriculum for police and an awareness program for Illinois residents. It also provides for a commission to oversee and advise the campaign. But the law went into effect June 1, so its details and impact aren’t yet clear.

Stoneback said she would like to see the governor’s office support a package of gun safety legislation, including strengthening background checks with policies like mandatory fingerprinting and applicants having to go in person to a law enforcement agency.

"The Highland Park police — they were very familiar with the shooter and his family. They’d been called multiple times. They knew something was going on," she said. "If in order to do the background check, the shooter and his father would have had to go into the local police department, there would have been further scrutiny and — hopefully — it would have been prevented."

Raising awareness among the general public of red flag laws is critical, she added.

"A lot of people don't know that they have this tool at their disposal," Stoneback said. "And with all the mass shootings that we've been seeing over and over, it’s absolutely important that everyone understands that they can and should go to law enforcement if they see warning signs."

Staff writer Amy Sherman contributed to this article.

RELATED: Ask PolitiFact: What are red flag gun laws and do they keep people safe?

RELATED: All of our fact-checks about guns

RELATED: Polls consistently show high support for gun background checks

Our Sources

ABC News, Highland Park parade mass shooting suspect charged with 7 counts of first-degree murder, July 5, 2022

Reuters, July 4 parade shooting suspect slipped past Illinois "red flag" safeguards, July 6, 2022

Washington Post, Highland Park suspect’s father sponsored gun permit application, police say, July 6, 2022

CNN, Highland Park gunman admitted to firing on parade crowd and contemplated attack in Madison, Wisconsin, officials say, July 6, 2022

Ilga.gov, H.B. 1092, Enrolled August 13, 2021

Ilga.gov, Firearms Restraining Order Act, Effective January 1, 2019

Ilga.gov, H.B. 0900, p. 542, Sec. 132, Enrolled April 19, 2022

Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, Firearm Restraining Orders in Illinois, March 11, 2022

Speak for Safety Illinois, How to Get a Firearm Restraining Order: Information for Law Enforcement

Six-Month Firearms Restraining Order Form, Illinois

Verified Petition For Firearms Restraining Order, Illinois

CBS News, Illinois "red flag" laws rarely used outside DuPage County, June 14, 2022

PBS News Hours, Lake County, Illinois prosecutor gives update on arrest of alleged Highland Park shooter, July 6, 2022

Rev.com, Authorities Speaks After Highland Park Shooter Makes First Court Appearance, July 6, 2022

Email interview, Dr. Traci Kurtzer, July 6, 2022

Illinois State Police, Redacted Highland Park Police Department Clear and Present Danger Report Reference Highland Park July 4 Parade Shooting, July 6, 2022

Illinois State Police, Highland Park Shooting Update, July 5, 2022

Illinois State Police, Highland Park Shooting, July 5, 2022

Illinois State Police, Clear And Present Danger Process Information, July 6, 2022

Telephone Interview, Denyse Stoneback, June 9, 2022

Illinois Department of Human Services, Clarifies Who Must Report Dangerous Activity and What Constitutes "Clear and Present Danger," January 13, 2014

Washington Post, Threats from Highland Park suspect drew police attention in 2019, July 5, 2022

Telephone interview, Denyse Stoneback, July 7, 2022

Email interview, Dr. Traci Kurtzer, July 8, 2022

Telephone interview, Stuart Reid, July 9, 2022

Email interview, Stuart Reid, July 9, 2022

ABC News, Police determined Highland Park shooting suspect posed 'clear and present danger' after past threat, July 8, 2022