Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

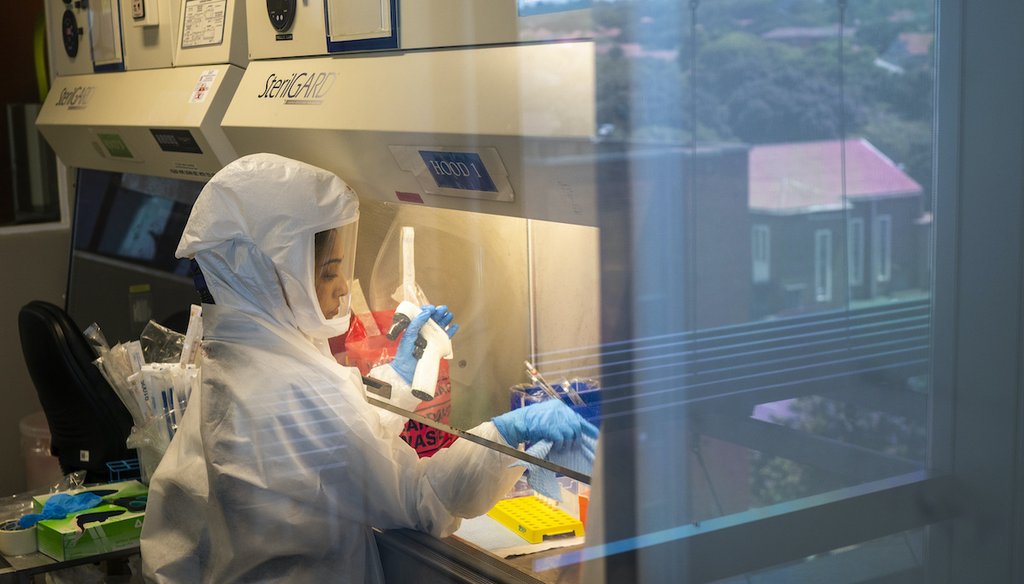

Scientists at the Africa Health Research Institute in Durban, South Africa, research and analyze the omicron variant of the COVID-19 virus on Dec. 15, 2021. (AP)

As the omicron variant of COVID-19 loosens its grip on the United States, public health officials and lawmakers are deliberating which rules and restrictions to ease.

But ever-evolving pandemic public health guidance and recent efforts by states to lift restrictions have given rise to social media claims that contend something nefarious is afoot. Scientists and health officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci of the National Institutes of Health have been lying about COVID-19 the entire time, they say.

"When the talking heads come out and say that we can ease up on restrictions because ‘The science is changing’ understand that the science never supported any of their measures all along," said one viral post by a chiropractor who has made false claims about the pandemic in the past. "What they’re really saying is that ‘The Narrative is changing.’ People are no longer buying The Narrative as it was and they have to try to sell you something else."

Another Facebook post, in the form of a graphic, categorizes a number of statements as being labeled "conspiracy theories" a year ago and "truth" now. They include "vaccinated can spread COVID" and "3rd and 4th shot."

Among critics, Fauci is the face of that changing narrative. We’ve seen video montages, political ads, and politicians’ social media posts that harken to statements they say he’s made and describe those statements as lies.

Sign up for PolitiFact texts

At the heart of these claims is widespread misunderstanding about how the scientific method works.

It is a perspective informed in part by frustration. Changing guidelines impact people’s daily lives. But the claims ignore the realities and challenges presented by a global pandemic caused by an emerging virus, researchers and science experts told us.

Scientists and doctors are worn down by the narrative.

"These kinds of charges are frustrating," said Sarah Richardson, a science historian at Harvard University. "They reflect a misunderstanding of how science works, how public health policy is created, and how empirical science and public health policy relate to one another."

Scientific findings are often confusing and conflicting. But evolving research and changing guidelines aren’t unprecedented or shocking, nor are they indicative of something nefarious.

"I can hardly blame people for feeling confused, but the problem is how this has been used politically," said Dr. Lynn Goldman, dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University. "I think there has been a deliberate effort to take advantage of that kind of confusion by accusing people of purposely misleading the public and there is no way that that has been happening — it’s not reality."

How COVID-19 impacted science

Marilyn Mar, right, and Nai-Hua Jeng analyze samples from suspected COVID-19 patients at the Stanford Clinical Virology Laboratory on Feb. 3, 2021, in Palo Alto, Calif. Scientists analyze samples for genetic changes, watching for mutations. (AP)

Science is hard. COVID-19 made it harder. One reason is simply the unusually lengthy timeline of this pandemic.

Most traditional epidemics run though communities over intervals of several months, said Dr. David Jones, an epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health and professor of the culture of medicine at the university’s history of science department.

"Too short of a time for researchers to launch and analyze studies that could have changed their thinking," he said.

The scientific process takes time. It involves a series of observations and hypotheses that are followed up with tests and experiments that are tweaked and fine-tuned along the way. Heading into three years of COVID-19, it’s to be expected that scientific consensus — when it can be achieved — would change. When you add in a rapidly-evolving virus like SARS-CoV-2 which has impacted vaccine efficacy and the need for boosters, things get more complicated.

"Someone has an observation, they do a study to test it, they learn something about it. And, as we learn more over time, we find out nuances," said Dr. Georges Benjamin, executive director at the American Public Health Association. "With COVID-19, we didn't have a static physical or biological object. It has been changing rapidly and we are altering the research along with it. The facts of the science haven't changed, the experiments and the virus have."

As scientists did their work, thousands were dying every day. Public health officials still had to give guidance with the goal of trying to keep as many people as safe as possible.

There were so many mysteries to solve when SARS-CoV-2 first emerged. No. 1: How was it transmitted? At first, many scientists believed, wrongly in hindsight, that it would behave similarly to SARS, a coronavirus that caused an outbreak in 2003. That virus, formally called SARS-CoV-1, caused an outbreak that lasted a short period. This is due, in part, to the fact that asymptomatic people could not spread it.

With its asymptomatic spread, COVID-19 turned out to be to SARS what a fox is to a dog, Goldman said: "They're both canines, but they’re very different animals."

There was no handbook for this new virus.

"Even just logically giving advice on how other members of the very same family of coronaviruses — a lot of that didn’t work," Goldman said. "Controlling those viruses is completely different from controlling COVID. But I think people tried very hard to do everything they could to save lives."

Among pandemics in history, COVID-19 stands alone. But experts said the 1918 influenza pandemic provides a good example of how scientific understanding develops in such a crisis.

The 1918 pandemic had three main waves spanning one to two years. Scientists kept trying to identify its cause. At the time, they believed that a number of bacteria were responsible for the outbreak, only to discover years later in the 1930s that the cause was a virus.

But the scientists who had incorrectly proposed a bacterial origin weren’t "lying," experts said. They were doing hard science in a crisis setting with inadequate tools, which can lead to wrong answers.

It’s also important to acknowledge the role that interest groups play in challenging what are sometimes unpopular scientific findings. There is a long history, going back to tobacco in the 1950s or climate change in the 1980s, where interest groups highlighted the imperfections of the scientific process in order to advance their own interests.

Science is easy to critique as studies vary in terms of scale and robustness, Jones said. If science is used to regulate interests that profit from lack of regulation, it makes sense that those groups would characterize the scientists as liars.

"Messaging from the CDC and NIH has left a lot to be desired, and political interests shape it, but that doesn’t mean that Fauci was ‘lying,’" Jones said.

Confusion over masks

Kindergarten teacher Karen Drolet, left, works with a student at Raices Dual Language Academy, a public school in Central Falls, R.I., Wednesday, Feb. 9, 2022. (AP)

Mask-wearing quickly became one of the most volatile aspects of the pandemic. Answers to questions about which masks to wear, where to wear them and who should wear them have fluctuated with time and understanding.

Before COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic, Fauci advised the general public against wearing masks. This was due to initial confusion about how COVID-19 was transmitted and concerns about mask shortages for essential workers. When it became clear that there wouldn’t be a shortage and that public mask-wearing, along with social distancing, could greatly reduce transmission, recommendations changed.

Scientists still believe that masks are effective at preventing illness — that hasn’t changed. But public health guidance around masks has. That’s because scientific understanding has changed about what types of masks are most effective in the face of different COVID-19 variants and in different settings. Once used widely outside, masks are now known to be most useful indoors and in crowded spaces, where risk of transmission is far higher.

"The first message of no masks was absolutely wrong, because (not wearing a) mask completely exposes you. Cloth masks that are multi-layered offer better protection, but the best is a well-fitting N95 mask," Benjamin said. "But it’s a spectrum of protections, and we really need to talk about this in terms of risk and degrees of protection."

Also at play in masking recommendations: rises and falls in infection rates and an upward trend in vaccination rates. With the CDC poised in late February to again revise its masking guidelines amid dropping COVID-19 infections, Dr. Ashish Jha, dean of Brown University School of Public Health, said it makes sense to think about masks as we think about raincoats.

"You wear it when it's raining," he said in a Feb. 23 interview with NPR. "You take it off when it stops raining. And if we think of masks in that way, then yeah, during surges, we should have masks, and everybody should be wearing them. And when the surge ends, we should take off our masks."

Masks have also been hard to study, experts said

Masking can be "highly context-specific," Harvard’s Richardson said: "Are other people masking? Are they vaccinated and boosted? What kinds of masks? What is the level of transmission in the community? Are they mandated? Are other mitigation policies in place?"

The question gets more complicated when it’s about masking in schools.

"Do mask mandates in elementary schools help? I suspect you could find scientific articles that have drawn different conclusions from their data," Jones said. "This is in part because good science is hard to do — some studies might be methodologically better than others and therefore closer to the ‘right answer’ — in part because contexts matter. Was the study done in warm or cold weather? Were the students indoors for eight hours at a stretch, or for less time? etc. Will a clear answer ever emerge? I’m really not sure."

These uncertainties are essential to the scientific process, but are like firewood for skeptics.

Then there’s political pressure. As public sentiment about the pandemic shifts, we’ve seen a number of Democratic lawmakers take action to lift mask mandates and ease other restrictions.

While politics most certainly plays a role in some of these decisions, criticism of those actions fails to recognize that the landscape looks different now than it did when these rules were put in place. Among the many new factors are vaccines, case declines, optimism over news of milder variants, and mounting public concern about mental health struggles.

"Creating public health policy requires uniting a wide range of constituencies around a shared platform, weighing costs and benefits," Richardson said. "This is a slow-moving process, embedded in our democratic systems of governance, with its own constraints and inertias."

Public messaging errors

Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, speaks during the daily briefing at the White House in Washington, Wednesday, Dec. 1, 2021. (AP)

Our Sources

Facebook post, Feb. 9, 2022

Facebook post, Feb. 11, 2022

Journal of Science Communication, Follow the scientists? How beliefs about the practice of science shaped COVID-19 views, Nov. 15, 2021

Washington Post, ‘Follow the science’: As the third year of the pandemic begins, a simple slogan becomes a political weapon, Feb. 11, 2022

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, The Deadliest Flu: The Complete Story of the Discovery and Reconstruction of the 1918 Pandemic Virus, Accessed Feb. 20, 2022

US National Library of Medicine, Discovery and characterization of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus in historical context, May 22, 2008

NPR, Ahead of new masking guidelines, White House wants to stop mixed messages, Feb. 23, 2022

Kaiser Family Foundation, The Implications of COVID-19 for Mental Health and Substance Use, Feb. 10, 2022

Pew Research Center, Americans’ Trust in Scientists, Other Groups Declines, Feb. 15, 2022

Email interview, Dr. David Jones, epidemiology professor at Harvard T.H Chan School of Public Health and professor of the culture of medicine at the university’s History of Science Department, Feb. 18, 2022

Phone interview, Dr. Georges C. Benjamin, executive director at the American Public Health Association, Feb. 18, 2022

Phone interview, Dr. Lynn Goldman, dean of the Milken Institute School of Public Health at George Washington University, Feb. 21, 2022

Email interview, Sarah Richardson science history professor at Harvard University’s History of Science Department, Feb. 21, 2022