Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

A woman walks near a church in Nuuk, Greenland, on March 7, 2025. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

As the Trump administration sets its sights on controlling Greenland, White House official Stephen Miller questioned Denmark’s authority over the ice-covered island.

-

Experts say Greenland’s status as part of Denmark is rock solid and any attempt to take over Greenland would flout international law.

After capturing Venezuelan leader Nicolás Maduro and saying the U.S. was taking control of the South American country, President Donald Trump and others in his administration suggested that Greenland could be the next U.S. target.

The day the U.S. took Maduro into custody to face U.S. drug-trafficking charges, Katie Miller, wife of senior White House aide Stephen Miller, posted on X a map of Greenland overlaid with the U.S. flag. "Soon," the caption said.

The next day, CNN anchor Jake Tapper asked Stephen Miller about Greenland. It’s geographically the world’s largest island — about five times the size of California — and has about 56,000 residents. Denmark colonized it centuries ago, and later incorporated it into Denmark.

Miller said the Trump administration’s longstanding policy is that "Greenland should be part of the United States."

When Tapper asked whether the administration would rule out military action, Miller said, "The real question is: By what right does Denmark assert control over Greenland? What is the basis of their territorial claim? What is their basis of having Greenland as a colony of Denmark?"

White House spokesperson Anna Kelly told PolitiFact that Trump is "confident Greenlanders would be better served if protected by the United States from modern threats in the Arctic region."

We asked experts about the history of the Denmark-Greenland relationship and Greenland’s status under international law. They agreed Greenland’s status as part of Denmark is rock solid and that any attempt to take over Greenland would flout international law.

What the Trump administration has floated

U.S. officials have repeatedly expressed interest in controlling Greenland, which is located between the United States and Europe. The naval corridor between Greenland, Iceland and the United Kingdom, called the "GIUK Gap," is a strategic channel in the Arctic because it is a main transit route for Europe, the Americas and Russia. Greenland also has potentially valuable mineral deposits.

"We need Greenland from the standpoint of national security," Trump told reporters Jan. 4 aboard Air Force One.

Two days later, the White House issued a statement that Greenland is "vital to deter our adversaries in the Arctic region" and that Trump and his team are "discussing a range of options" which could include utilizing the U.S. military.

If the United States did attempt to seize Greenland, it is unlikely to face military resistance, wrote Ivo Daalder, who served as U.S. ambassador to NATO under President Barack Obama.

"Taking Greenland won’t be difficult," Daalder wrote Jan. 6. "Its population of 50,000 won’t be able offer much resistance, nor will Denmark want to enter a fight it cannot win." (Miller said something similar in his interview with Tapper: "Nobody’s going to fight the United States militarily over the future of Greenland.")

Daalder warned, though, that such U.S. military action could damage the credibility of NATO, the mutual defense pact the U.S. has led for decades.

"To suggest that American security in the Arctic requires that it owns Greenland implicitly indicates that the NATO security commitment is hollow and insufficient for its security," Daalder wrote. "That’s hardly a reassuring message to the other 31 NATO members, many of whom face far more immediate threats than the United States."

What is the basis of Denmark’s claim to Greenland?

Denmark’s colonization of Greenland dates to the 1720s. In 1933, an international court settled a territorial dispute between Denmark and Norway, ruling that as of July 1931, Denmark "possessed a valid title to the sovereignty over all Greenland."

In 1940, after Germany invaded Denmark, the U.S. assumed responsibility for Greenland’s defense and established a military presence on the island that remains today.

But Greenland has not been a colony for more than three-quarters of a century, said Diane Marie Amann, a University of Georgia emerita law professor.

After World War II, colonialism "was decidedly rejected in the United Nations charter," said Tom Ginsburg, a University of Chicago international law professor.

After the 1945 approval of the United Nations charter — the organization’s founding document and the foundation of much of international law — Denmark incorporated Greenland through a constitutional amendment and gave it representation in the Danish Parliament in 1953. Denmark told the United Nations that any colonial-type status had ended, and the United Nations General Assembly accepted this change in November 1954, said Greg Fox, a Wayne State University law professor. The United States voted to accept the new status.

Since then, Greenland has, incrementally but consistently, moved toward greater autonomy.

Greenlandic political activists successfully pushed for and achieved home rule in 1979, which established its parliament. Today, Greenland is a district within the sovereign state of Denmark, Amann said, with two elected representatives in Denmark’s parliament. These representatives have full voting rights — greater authority than the U.S. gives congressional delegates for its territories such as Puerto Rico, Guam and the Virgin Islands.

In 2008, Greenlanders voted 76% to 24% in favor of expanding the island’s autonomous status, in a non-binding referendum. This led to a 2009 law that recognized Greenlanders as a distinct people, as well as making Greenlandic the island’s official language and granting Greenland power over its mineral resources.

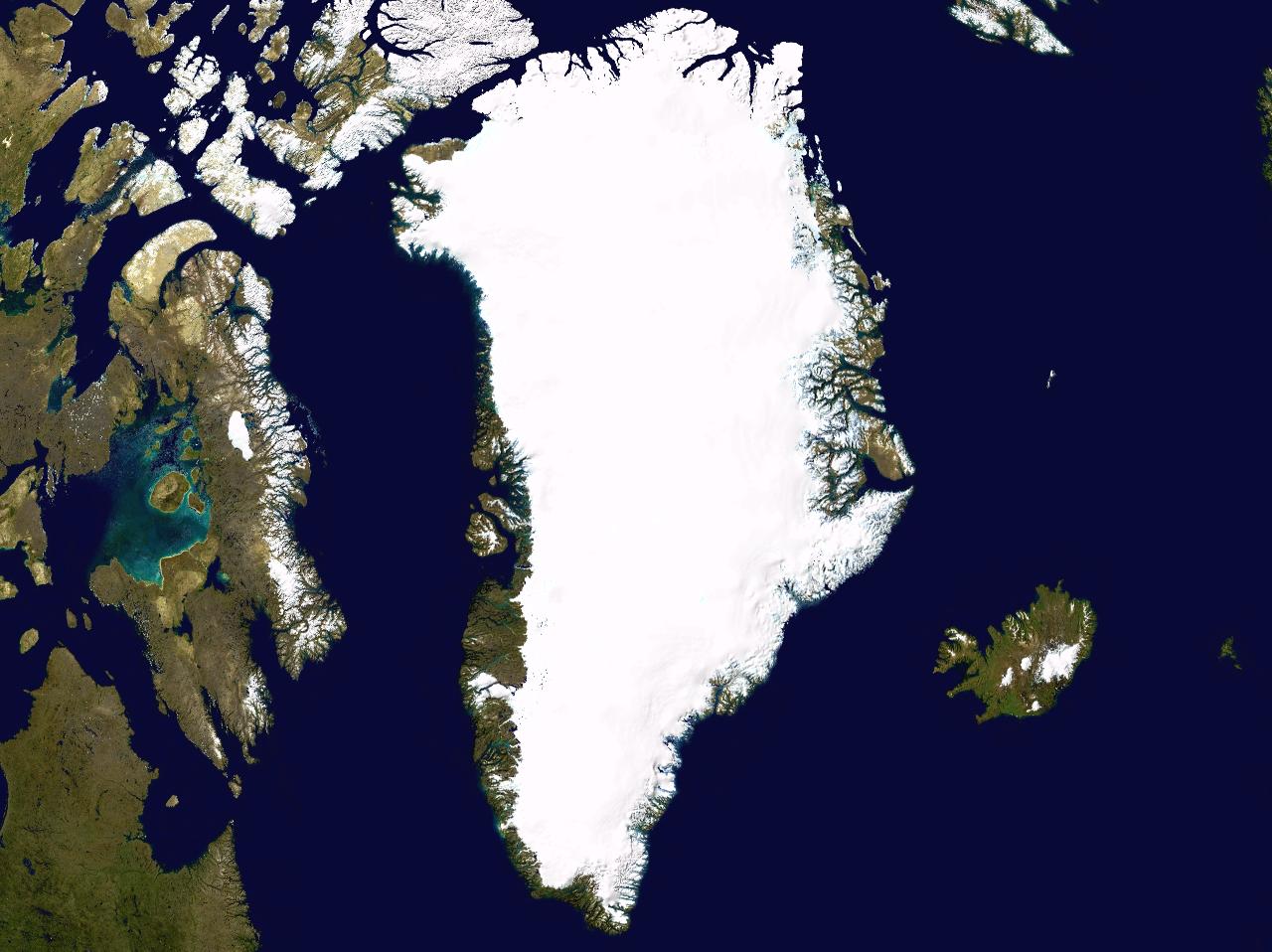

A satellite photo highlighting Greenland, as well as Iceland and the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. (NASA/public domain)

What is Greenland’s status under international law?

The 2009 law established that the Greenlandic people have the power to pursue independence from Denmark if they choose. To date, they have not done so.

While Danish law gives Greenland substantial local control, "That doesn’t mean that Greenland is any less a part of Denmark for international law purposes," Fox said. "Because Greenland is fully incorporated into Denmark, it means that under international law, Denmark can both represent Greenland's interests and people to other countries and can assert its rights if other countries cause it harm."

Fox compared Greenland’s status within Denmark to Michigan’s or Ohio’s within the U.S. "The U.S. represents their interests and the interests of their people to the rest of the international community," he said. Denmark’s sovereignty "covers all its territory, including Greenland," Fox said.

The United Nations’ charter, to which the U.S. is a signatory, says members must refrain from threatening or using force "against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state." Amann said this means that "no other country may assist or secure such a secession, whether by the actual use of military force or by threatening to use such force."

If Greenland "wanted Denmark to transfer them to the United States, they might be able to request that," Ginsburg said. "But that’s not the situation now."

U.S. history of recognizing Denmark’s authority over Greenland

The U.S. has recognized Denmark’s "territorial sovereignty" over Greenland on multiple occasions, beyond the 1953 United Nations vote:

-

The United States’ purchase of the Danish West Indies — now known as the U.S. Virgin Islands — included a 1917 agreement with Denmark that mentioned Greenland. Then-Secretary of State Robert Lansing said the U.S. government "will not object to the Danish Government extending their political and economic interests to the whole of Greenland."

-

In 1946, the U.S. under President Harry Truman formally proposed buying Greenland. Denmark declined to sell.

-

In 1951, the U.S. signed a Greenland-related defense agreement with Denmark, which it updated in 2004. The agreement, which affirmed and outlined the American military’s presence, said in its first paragraph that Greenland’s status had changed "from colony to that of an equal part of the Kingdom of Denmark."

Collectively, the existence of these treaties "means the United States believed (Denmark) was the country with authority over Greenland," Fox said.

PolitiFact Researcher Caryn Baird contributed to this report.

RELATED: Fact-checking Donald Trump on promised U.S. oil company investment in Venezuela

RELATED: What are the charges against Venezuela's Maduro? How can the US indict foreign politicians?

Our Sources

CNN, Miller says Greenland should ‘obviously’ be a part of US, Jan. 5, 2026

CNN, Analysis: Trump wants to take Greenland because it’s there, Jan. 7, 2026

Donald Trump, remarks aboard Air Force One, Jan. 4, 2026

Katie Miller’s X post, Jan. 3, 2025 (Archived)

Danish Institute for International Studies, Why is Greenland part of the Kingdom of Denmark? A Short History, Oct. 9, 2025

Medieval Histories, Greenland Was Part of Denmark for 1000 years, Jan. 6, 2026

Department of State Office of the Historian, Convention Between the United States and Denmark for the Cession of the Danish West Indies, accessed Jan. 7, 2026 (Archived)

Oxford Reports on International Law, Legal Status of Eastern Greenland, Denmark v Norway, Judgment, April 5, 1933

Maria Ackrén, "Referendums in Greenland - From Home Rule to Self-Government," 2019

SciencesPo, Greenland, Denmark and the US: the meaning of the colonial past to the ongoing dynamics, Feb. 14, 2025

The Library of Congress, Greenland’s National Day, the Home Rule Act (1979), and the Act on Self-Government (2009), June 21, 2019

History.com, The U.S. Bought 3 Virgin Islands from Denmark. The Deal Took 50 Years, May 28, 2025

U.S. Department of State, Agreement between the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and DENMARK, Aug. 6, 2004

United Nations, 849 Cessation of the transmission of information under Article 73 e of the Charter in respect of Greenland, accessed Jan. 8, 2026

United Nations, "Committee on Information from Non-Self-Governing Territories Hears Danish Statement on Greenland," Sept. 8, 1954

United Nations, Greenland and the UN: Colony or not a colony – that was the question, accessed Jan. 8, 2026

United Nations Digital Library, Cessation of the transmission of information under Article 73 e of the Charter in respect of Greenland, accessed Jan. 8, 2025

Center for Strategic and International Studies, "The GIUK Gap: A New Age of A2/AD in Contested Strategic Maritime Spaces," Sept. 12, 2024

The Conversation, "Greenland is rich in natural resources — a geologist explains why," Jan. 8, 2026

Tampa Bay Times, "How Iceland fits into Trump’s plans and how Icelanders feel about it," Sept. 10, 2025

CNN, The US has tried to acquire Greenland before – and failed, Jan. 7, 2026

Ivo Daalder, "The Consequences of Taking Greenland," Jan. 6, 2026

The New York Times, GREENLAND STATUS SET; U.N. Adopts Resolution Putting It Under Danish Realm, Nov. 23, 1954

The New York Times, Buy Greenland? Take It? Why? An Old Pact Already Gives Trump a Free Hand., Jan. 7, 2026

The New York Times, Greenland’s Minerals: The Harsh Reality Behind the Glittering Promise, March 3, 2025

Politico, "White House: Trump ‘discussing a range of options’ to take Greenland — including military force," Jan. 6, 2026

PolitiFact, What are the charges against Venezuela's Maduro? How can the US indict foreign politicians? Jan. 5, 2026

PolitiFact, Fact-checking Donald Trump on promised U.S. oil company investment in Venezuela Jan. 5, 2026

Email interview with Mark F. Cancian, senior adviser at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Jan. 7, 2026

Email interview with Diane Marie Amann, an emerita law professor at the University of Georgia, Jan. 7, 2026

Email interview with Tom Ginsburg, international law professor at the University of Chicago, Jan. 7, 2026

Email interview with Greg Fox, Wayne State University law professor, Jan. 7, 2026