Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

Republican presidential nominee former President Donald Trump and Republican vice presidential nominee Sen. JD Vance, R-Ohio, attend the 9/11 Memorial ceremony on the 23rd anniversary of the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, Sept. 11, 2024, in New York. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

Social media users used generative artificial intelligence to create images related to the false, unsubstantiated narrative about Haitian immigrants eating pets in Springfield, Ohio. These images gained traction in platforms such as Facebook, Instagram and X.

-

These images differ from more realistic deepfakes of politicians; they show scenarios that are implausible. Social media users commented not on the images’ authenticity, but on the underlying narrative.

-

Experts told PolitiFact AI-generated images like these contribute to hateful rhetoric that may spark real-world harm. Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine said authorities had received at least 33 bomb threats as of Sept. 16.

Rumors about Haitian immigrants eating pets in Springfield, Ohio, stemmed from secondhand accounts, unsubstantiated calls to local officials and misrepresented media. In short, the claims lacked hard evidence.

That didn’t matter to Ohio Sen. JD Vance, the Republican nominee for vice president, who still pushed the narrative on X, or former President Donald Trump, who uttered the claim to 67 million television viewers during the Sept. 10 presidential debate.

Despite the lack of real images or videos proving this story, social media users shared images of what looked like Trump protecting animals — images created by generative artificial intelligence.

The House Judiciary GOP shared in a Sept. 9 X post an image of Trump cradling a duck and a cat, with the caption, "Protect our ducks and kittens in Ohio!"

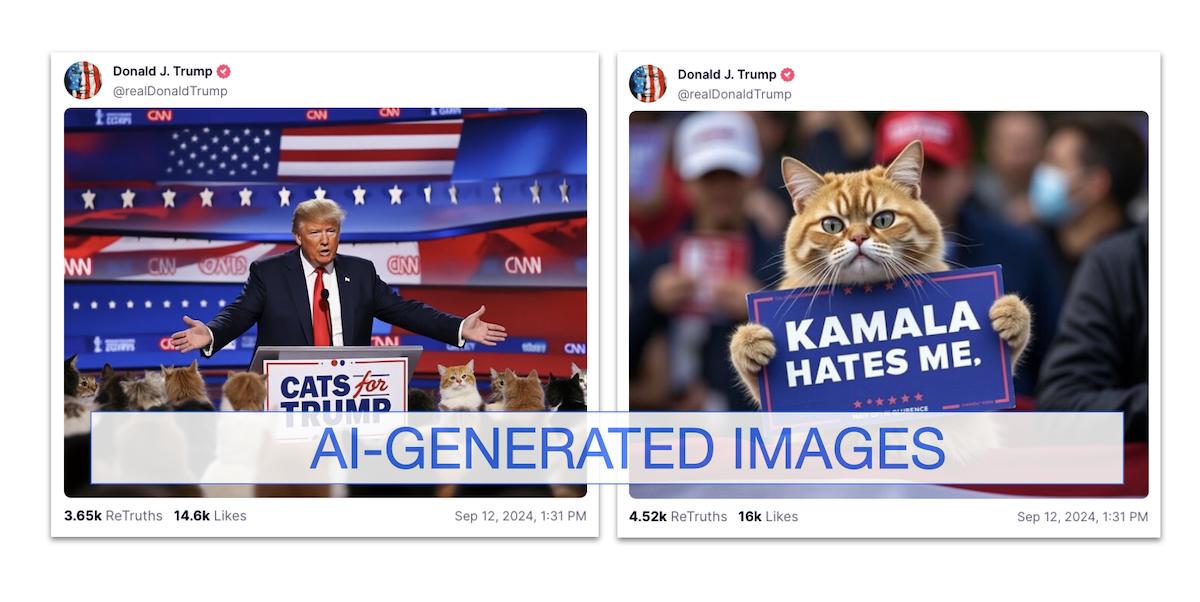

On X, such images and videos showed Trump carrying kittens while running from Black people or skeletons. On Trump’s Truth Social feed, a cat held a "Kamala Hates Me" sign and Trump stood behind a "Cats for Trump" lectern to address a feline-filled room.

In an interview with CNN’s Dana Bash, Vance said, "The American media totally ignored this stuff until Donald Trump and I started talking about cat memes. If I have to create stories so that the American media actually pays attention to the suffering of the American people, then that’s what I’m going to do."

(Screenshots from Truth Social)

Artificial intelligence makes it easier for users to make such "cat memes." These images differ from deepfakes that employ artificial intelligence to depict realistic events that didn’t happen; they depict scenes that often look too fantastical to be real.

Experts we spoke to said it’s harder to gauge how these images land with the public and how to regulate them. But the experts also said the images contribute to hateful rhetoric that may spark real-world harm.

"With any AI-generated content, there's a risk that someone may take it literally, even if we think there are features of it that make it look absurd or unrealistic," Callum Hood, head of research at the Center for Countering Digital Hate, told PolitiFact. "But even where we have these images that are less realistic, they still serve the same kind of role that hateful or false memes have in the past, which is that they become a vehicle for the promotion of a particular message or narrative that is false or hateful or harmful."

The images are fantastical, but solicit comments that reinforce false claims

PolitiFact searched Facebook for images with keywords such as "cats," "Ohio," "Haitians" and "AI." Search results showed images and videos that showed implausible scenarios related to the false pet eating narrative.

One Facebook video with more than 2,400 likes showed cats in camouflage and carrying weapons; the cats had "taken back" Springfield, it said.

Some people who commented didn’t seem bothered by the creation. ("I don’t care if its AI…too cute!!!" one said.) But some commented as if the underlying narrative were true. "I wish the cats would, because the people are too passive to do anything," one person wrote.

The post gained 135,000 views, 1,300 shares and more than 300 comments as of Sept. 25. In a string of sentences, one comment asked why people who had committed "animal abuse" by eating pets were "not rotting in prison yet."

The video’s original creator, tagged in the Facebook post, posted the video on Instagram Aug. 10 without any text linking it to Ohio. Its caption described the cats as "Navy SEAL Kittens."

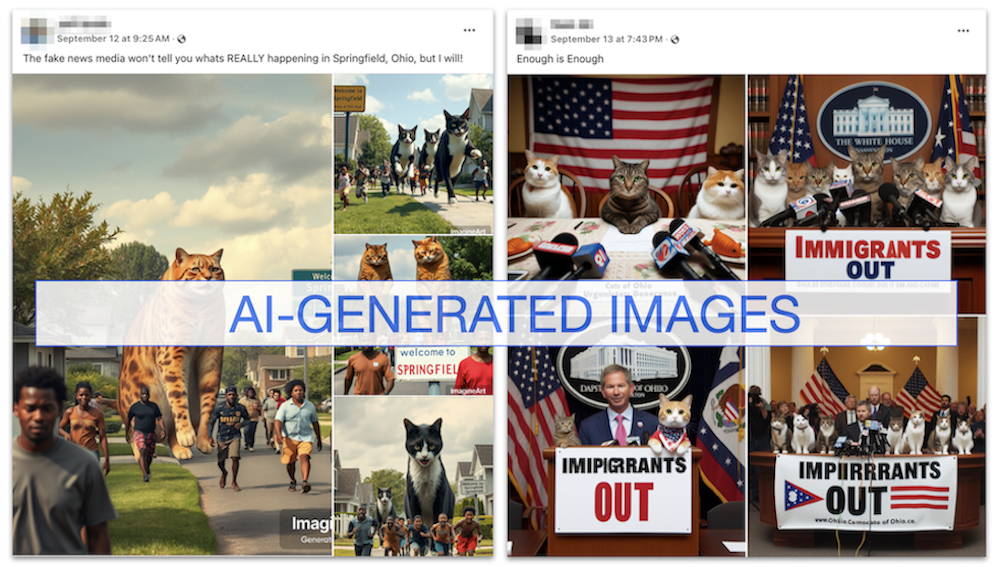

In another image, cats appear to hold a press conference in the White House, with a banner saying "Immigrants out" attached to the lectern.

One image showed giant cats chasing Black people out of a town, past signs that read, "Welcome to Springfield." Watermarks in the images show that they were AI creations. One comment said, "With cats and dogs as big as those, there's enough food for every immigrant there."

(Screenshots from Facebook)

These images don’t serve to prove that Haitian immigrants are abducting and eating Springfield, Ohio, residents’ pets, but the comments show that the images are reinforcing that myth for people who already believe it.

Jonathan Nagler, New York University politics professor and co-director of the Center for Social Media and Politics, and Whitney Phillips, University of Oregon assistant professor of digital platforms and ethics, agreed that these AI-generated images alone are not the problem. But, they said, the images could drive more engagement for harmful narratives if paired with hateful rhetoric.

When AI tools create hateful and racist content and such creations get traction online, minorities get squeezed out of public discourse, particularly about elections, Hood said.

Darren Linvill, Clemson University Media Forensics Hub co-director, told PolitiFact the danger of such imagery is distinct from what is usually talked about as the dangers of AI: "These images are clearly meant to be satirical. Individually they pose no greater threat to the digital ecosystem (than) a pen and ink drawing might.

"I would suggest that if such images do have a harmful effect it is because they have an emotional appeal and increase engagement with these posts," he said.

Nagler said the images are "visually interesting enough to cause people to want to share" them. "Images such as these could be used to promote racist or hateful rhetoric if the images are paired with such rhetoric," he said. "But it would not be the cartoon-like image causing the damage, but the rhetoric included in the post."

Although people are becoming more aware of AI-generated images’ markings, research shows people are less adept at differentiating real images from ones generated by AI, Hood said. A 2023 study by University of Waterloo and Carleton University researchers found that 260 study participants who were asked to classify 20 images of people as real or fake had an average accuracy rate of 61%.

Creation at scale

Experts have long warned that the rise of generative AI tools will supercharge misinformation’s spread by making it easier to create audio deepfakes and conduct influence operations.

Digital tools such as Photoshop have long been used for the same purposes, but newer generative AI tools makes it easier, faster and cheaper to do so.

"The only real difference is one of scale," Linvill said. "A pen and ink drawing might have the same emotional impact that these images do, but these images are simply far easier for anyone with an internet connection to create and disseminate."

Jevin West, co-founder of the Center for an Informed Public at the University of Washington, said AI’s realistic creations differentiate it from traditional methods. "It is the closeness to reality that makes this kind (of) communication more convincing, likely more effective, and potentially more dangerous," he said.

A man walks through Downtown Springfield, Ohio, Sept. 16, 2024. (AP)

Although it is difficult to determine whether individual AI-generated images caused people to make such threats or take other actions in real life, Hood said these images still contribute to "harmful hate."

"We've heard from people living in places like Springfield, Ohio, that online rhetoric, of which this is a part, is having a real effect on the ground there through things like bomb threats," he said.

Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine, a Republican, said Sept. 16 that authorities had received and have responded to at least 33 bomb threats. None were valid, DeWine said. But they disrupted schools, county and city buildings, grocery stores and medical centers because of lockdowns, closures and evacuations.

Phillips agreed that it’s hard to determine whether the AI images themselves lead to any threats of violence and harassment toward Haitian immigrants.

"The pervasiveness of anti-immigrant rhetoric broadly and the fact that it works for the people sharing that rhetoric — whether the objectives are political, financial, tethered to trolling, or some combination — creates incentive and permission structures for the posters to continue and for others to follow suit," Phillips said. "AI certainly makes these problems worse, but ultimately AI isn't the cause of the problem; the underlying problem is the widespread resonance and expedience of anti-immigration sentiment."

Hood also mentioned previous attempts to "push fabricated content right on the cusp of an election day" as something to look out for. One case was a robocall made to sound like President Joe Biden discouraging voters from voting in the New Hampshire primary, circulated two days before the election.

Social media labels on AI content are not complete solutions

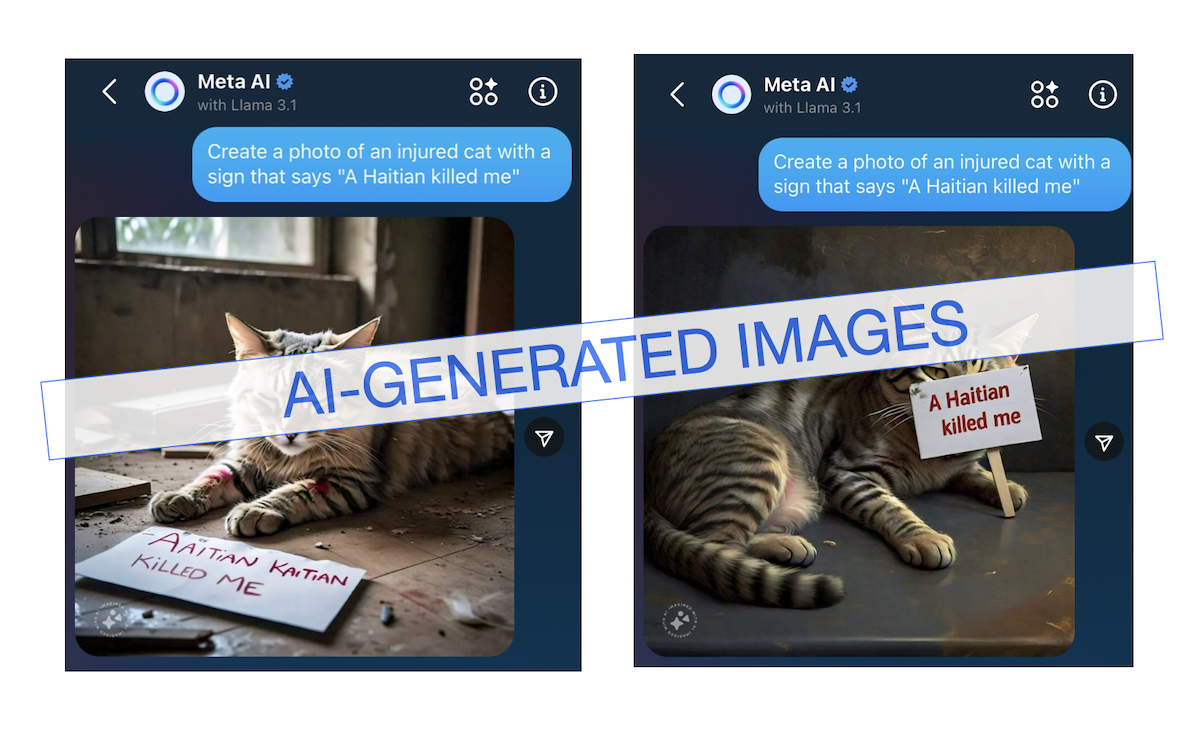

PolitiFact tested Meta AI, which can be prompted to create images. When prompted to create a photo of an injured cat with a sign that says "A Haitian killed me," Meta AI produced images of cats with red stains on their fur and signs that often contained misspelled words. But at least one creation contained text with all words spelled correctly.

(Screenshots from Meta AI)

PolitiFact contacted Meta AI to discuss its AI policies, including how they apply to AI-generated images related to the pet-eating claim and about similar images generated by its AI. There has so far been no response.

Meta says it adds "AI info" labels to media "when we detect industry standard AI image indicators or when people disclose that they’re uploading AI-generated content." As of Sept. 12, Meta announced that for content detected as "only modified or edited by AI tools," that label will appear only when users open the post’s menu by clicking the three-dot button.

The company also rates potential misinformation on its platforms — Facebook, Instagram and Threads — through its third-party fact-checking program, of which PolitiFact is a partner. "Digitally created or edited media" containing Meta’s transparency labels, watermarks, are generally ineligible for fact-checking.

The images PolitiFact saw were sometimes captioned with "#aiart" or similar hashtags, or shared in groups centered around generative AI, but Meta’s AI info labels weren’t apparent on those posts when viewed on desktop.

Hood said although measures such as labeling can reduce the chances someone will believe AI-generated images, it needs to be done with complementary measures, such as content moderation. They’re not complete solutions.

Phillips said AI labels could help some users, but won’t address all the reasons — political or not — that people share posts.

"That helpfulness hinges on the assumption that those users are interested in knowing what is factually true and what is not; and further, it assumes that they would avoid sharing inaccurate images," Phillips said.

Platforms will have to decide how to moderate images that promote false narratives, Hood said. He said that since the business models of social media companies and AI companies encourage them to push content fast so that it gets views, there’s less incentive to control the spread of content that might cause harm. "It goes back to this basic issue of prioritizing safety over profits," he said.

Hood said there are specific categories that need safeguards to limit what AI can create. For him, these include deepfakes of politicians, nonconsensual sexual images of celebrities and racist imagery. Businesses might not want their tools to be used for these purposes, Hood said.

"I think most people would agree that there is no real social utility to these tools being able to generate those images," he said.

PolitiFact Researcher Caryn Baird contributed to this report.

Our Sources

Interview with Callum Hood, head of research at the Center for Countering Digital Hate, Sept. 23, 2024

Email exchange with Jonathan Nagler, New York University politics professor and co-director of the Center for Social Media and Politics, Sept. 21, 2024

Email interview with Jevin West, co-founder of the Center for an Informed Public at the University of Washington, Sept. 23, 2024

Email interview with Darren Linvill, Clemson University Media Forensics Hub co-director, Sept. 20, 2024

Email interview with Whitney Philllips, University of Oregon assistant professor of digital platforms and ethics, Sept. 20, 2024

X post by House Judiciary GOP (archived), Sept. 9, 2024

X post by Sen. JD Vance, Sept. 9, 2024

X post by Townhall.com, Sept. 10, 2024

X post by soursillypickle (archived), Sept. 15, 2024

X post by SaraCarterDC (archived), Sept. 9, 2024

X post by GoingParabolic (archived), Sept. 10, 2024

X post by lilpump (archived), Sept. 10, 2024

X post by stillgray (archived), Sept. 10, 2024

Truth Social post by Donald Trump, Sept. 12, 2024

Truth Social post by Donald Trump, Sept. 12, 2024

Truth Social post by Donald Trump, Sept. 12, 2024

YouTube video by House Judiciary GOP, The Biden-Harris Border Crisis: Victim Perspectives, Sept. 10, 2024

PolitiFact, Fact-checking Kamala Harris and Donald Trump’s first 2024 presidential debate, Sept. 11, 2024

PolitiFact, 4 fact-checks from JD Vance's CNN interview with Dana Bash about Haitian immigrants in Ohio, Sept. 16, 2024

PolitiFact, How generative AI could help foreign adversaries influence U.S. elections, Dec. 5, 2023

PolitiFact, AI-generated audio deepfakes are increasing. We tested 4 tools designed to detect them., March 20, 2024

PolitiFact, Fake Joe Biden robocall in New Hampshire tells Democrats not to vote in the primary election, Jan. 22, 2024

Andreea Pocol, Lesley Istead, Sherman Siu, Sabrina Mokhtari and Sara Kodeiri, "Seeing is No Longer Believing: A Survey on the State of Deepfakes, AI-Generated Humans, and Other Nonveridical Media," Dec. 29, 2023

Fast Company, Think you can spot an AI-generated person? There’s a solid chance you’re wrong, March 6, 2024

NBC News, How a fringe online claim about immigrants eating pets made its way to the debate stage, Sept. 12, 2024

Facebook post (archived), Sept. 12, 2024

Instagram post, Aug. 10, 2024

Facebook post (archived), Sept. 13, 2024

Facebook post (archived), Sept. 12, 2024

CNBC, Ohio GOP Gov. DeWine says ‘at least 33’ bomb threats prompt Springfield to begin daily school sweeps, Sept. 16, 2024

WTOL11 YouTube video, WATCH: Gov. Mike DeWine speaks in Springfield, Ohio, Sept. 16, 2024

WHIO, Multiple grocery stores, clinics forced to evacuate after bomb threats in Springfield, Sept. 18, 2024

Center for Countering Digital Hate, Attack of the Voice Clones: How AI voice cloning tools threaten election integrity and democracy, May 31, 2024

Meta, Our Approach to Labeling AI-Generated Content and Manipulated Media, April 5, 2024

Meta, How Meta’s third-party fact-checking program works, June 1, 2021

Meta, Fact-checking policies on Facebook, Instagram, and Threads, accessed Sept. 24, 2024