Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

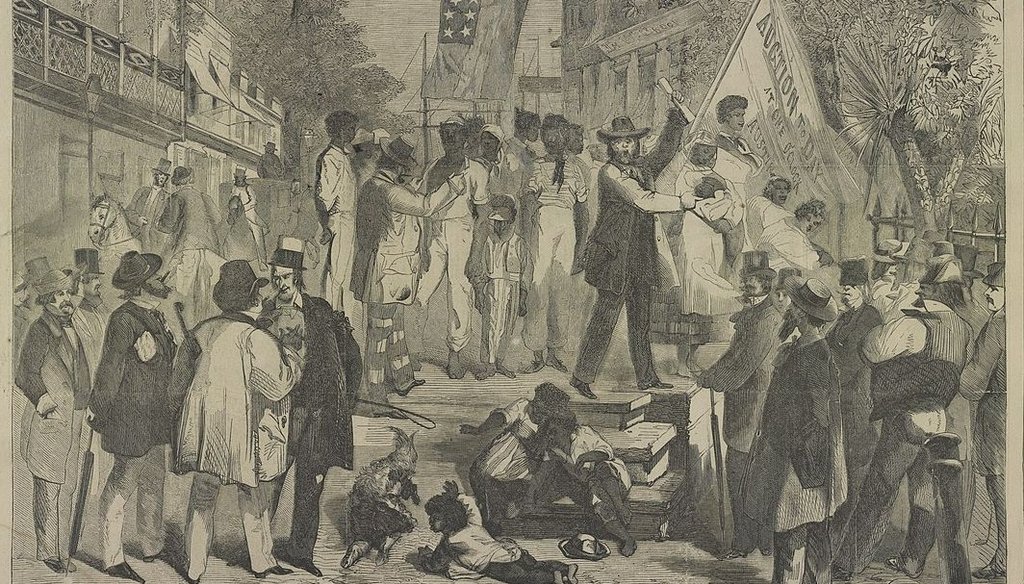

A slave auction; engraving from Harper's Weekly, 1861 (public domain)

William Faulkner famously wrote, "The past is never dead. It's not even past." That could describe some of the recent historical discourse on the presidential campaign trail.

First came Republican candidate Nikki Haley, who answered a question at a Dec. 27 event in Berlin, New Hampshire, about the Civil War’s cause. Haley’s answer didn’t refer to slavery, and instead cited "the role of government and what the rights of the people are." (She later said that "of course the Civil War was about slavery.")

Then, in Newton, Iowa, on Jan. 6, former President Donald Trump said the Civil War "could have been negotiated" rather than causing years of bloodshed.

Students and scholars of American history might be tempted to ask the presidential candidates to take a refresher course.

"Whatever individual people fought for can become complicated, but there’s no doubt that the Confederacy was founded on the basis of protecting enslavement," said William Alan Blair, a Penn State University historian and author of "Cities of the Dead: Contesting the Memory of the Civil War in the South."

With the Civil War’s history and framing becoming a recurrent theme in the days before crucial presidential primaries in Iowa and New Hampshire, we thought we’d clarify the causes and run-up to the pivotal conflict that raged from 1861 to 1864.

Saying the Civil War centered on slavery doesn’t mean that slavery was the war’s only cause. On some level, it was also a "clash of a traditional society," the South, and "a modernizing society," the North, said Michael Burlingame, a historian at the University of Illinois, Springfield and author of "Abraham Lincoln: A Life."

But slavery was the "central cause," Burlingame added.

The notion that differences over states rights caused the war, historians say, is inseparable from the reason that states rights became a sticking point: slavery.

"Whenever I hear politicians dodging the slavery question, often by saying the American Civil War was not about slavery but was about state's rights, I finish their sentences by adding, ‘to the tradition of owning Black people," said Marvin Dunn, an emeritus psychology professor at Florida International University and author of "The History of Florida: Through Black Eyes."

Paul Finkelman, a visiting professor at Marquette Law School and author of "Defending Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Old South, agreed with Dunn.

"If you go through the checklist to find something else that caused the war, it can’t be taxes, tariffs, or some other public policy issue," he said. "It’s all about slavery."

One need not take historians’ words on this question. Primary documents from the 19th century centered slavery as states were seceding from the union:

State declarations of secession: South Carolina’s declaration of secession, issued Dec. 24, 1860, uses a variation of the word "slave" 18 times, including mention of "an increasing hostility on the part of the non-slaveholding states to the institution of slavery" as being at the root of their secession.

Mississippi’s declaration of secession of Jan. 9, 1861, said, "Our position is thoroughly identified with the institution of slavery — the greatest material interest of the world."

And Texas’ secession ordinance, issued Feb. 1, 1861, said that "recent developments in federal affairs make it evident that the power of the federal government is sought to be made a weapon with which to strike down the interests and property of the people of Texas, and her sister slave-holding States, instead of permitting it to be, as was intended, our shield against outrage and aggression."

Not all of the secession documents described slavery this way, "but in those that don't, it is clearly implied," said Sean Wilentz, a Princeton University historian and author of "The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln."

The "corner-stone" speech: On March 21, 1861, Confederate Vice President Alexander H. Stephens presented slavery as one of the reasons behind the "revolution" that produced the Civil War.

The Confederacy’s constitution, Stephens said, "has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution — African slavery as it exists amongst us — the proper status of the (N)egro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution."

He added that the Confederacy’s "corner-stone rests upon the great truth that the (N)egro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition."

The Confederacy’s constitution: The Confederate constitution was explicit about mentioning slavery.

According to the Confederate constitution, "the right of property in said slaves shall not be thereby impaired." It further demanded that fugitives from slavery be returned rather than protected, and it said that in any future geographical expansion of Confederate territory, slavery "shall be recognized and protected."

"There was extensive, decades-long negotiation," said Martin P. Johnson, a historian at Miami University, Hamilton in Ohio and author of "Writing the Gettysburg Address."

It started with the discussions at the Constitutional Convention in 1787, when the framers, despite the reservations about slavery among some of them, let the importation of enslaved people to continue until 1808; required the return of fugitives from slavery; and counted an enslaved person as three-fifths of a free person for the purpose of congressional representation. The framers made these compromises because they were concerned that, without them, the southern states would reject the document.

Negotiations later produced the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and the Compromise of 1850.

As late as December 1860, just weeks after Lincoln’s election and a few months before hostilities broke out at Fort Sumter in South Carolina, Sen. John Crittenden of Kentucky offered the "Crittenden Compromise," which would have extended to the Pacific Ocean the line originally drawn by the Missouri Compromise, prohibiting slavery north of the 36°30' parallel but allowing it below that line. It died in committee.

The war’s start "was not a failure of negotiation or process," Johnson said. "It was about a fundamental difference of outlook, ideology, and understanding of the American experiment. Are we a nation founded in assuring the rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness for all? Or a compact to guarantee property only, specifically property in humans?"

Approving the Crittenden Compromise would have amounted to "a capitulation to pro-slavery principles and would have required Lincoln and the Republicans to abandon their bedrock commitment to the nonextension of slavery," said Georgetown University historian Adam Rothman, author of "Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South."

Eventually, the 1860 election decided the issue in Lincoln and the Republicans’ favor. But by then, neither side had the stomach for compromise.

The South "refused to negotiate coming back into the Union," Finkelman said.

As for the North, abandoning "halting the extension of slavery into the territories was a non-starter as far as Lincoln was concerned," Wilentz said.

In other words, historians say, the sides were at an impasse.

Black academics said they feel it viscerally when they see politicians mischaracterizing the Civil War’s history and origins.

"The lie about the history of slavery and the Civil War … revolves around the disposability of African Americans as human beings," added Carol Anderson, an Emory University African American Studies professor.

Our Sources

Washington Post, "Nikki Haley was asked what caused the Civil War. She made no mention of slavery," Dec. 28, 2023

Washington Post, "Trump says Civil War ‘could have been negotiated.’ Historians disagree," Jan. 6, 2024

South Carolina’s declaration of secession, Dec. 24, 1860

Mississippi’s declaration of secession, Jan. 9, 1861

Texas’ secession ordinance, Feb. 1, 1861

Confederate States of America, constitution, accessed Jan. 8, 2024

Alexander Stephens, "Corner-stone" speech, March 21, 1861

National Constitution Center, Constitutional Convention in 1787, accessed Jan. 8, 2024

National Archives, Missouri Compromise of 1820, accessed Jan. 8, 2024

Britannica.com, Compromise of 1850, accessed Jan. 8, 2024

Britannica.com, Three-Fifths Compromise, accessed Jan. 8, 2024

U.S. Senate, Crittenden Compromise, accessed Jan. 8, 2024

Email interview with James Oakes, emeritus professor of history at the CUNY Graduate Center and author of "The Crooked Path to Abolition: Abraham Lincoln and the Antislavery Constitution," Jan. 8, 2024

Email interview with Adam Rothman, Georgetown University historian and author of "Slave Country: American Expansion and the Origins of the Deep South," Jan. 8, 2024

Email interview with Sean Wilentz, Princeton University historian and author of "The Rise of American Democracy: Jefferson to Lincoln," Jan. 8, 2024

Email interview with Martin P. Johnson, a historian at Miami University-Hamilton in Ohio and author of "Writing the Gettysburg Address," Jan. 8, 2024

Email interview with Michael Burlingame, historian at the University of Illinois-Springfield and author of "Abraham Lincoln: A Life," Jan. 8, 2024

Email interview with William Alan Blair, Penn State University historian and author of "Cities of the Dead: Contesting the Memory of the Civil War in the South," Jan. 8, 2024

Email interview with Marvin Dunn, emeritus professor psychology at Florida International University and author of "The History of Florida: Through Black Eyes," Jan. 8, 2024

Email interview with Carol Anderson, Emory University African American Studies professor, Jan. 8, 2024

Interview with Paul Finkelman, visiting professor at Marquette Law School and author of "Defending Slavery: Proslavery Thought in the Old South," Jan. 8, 2024