Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

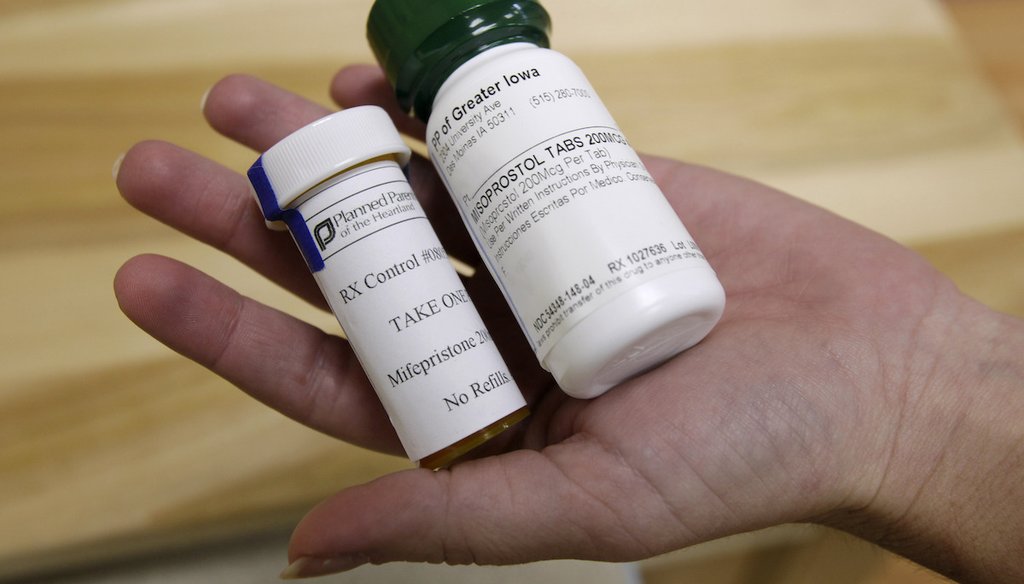

Bottles of abortion pills mifepristone, left, and misoprostol, right, are shown Sept. 22, 2010, at a clinic in Des Moines, Iowa. (AP)

Abortion opponents are using a new argument in their efforts to restrict abortion access: the environment.

The anti-abortion group Students for Life claimed that trace amounts of mifepristone — the first of two drugs taken for a medication abortion — are poisoning American wastewater.

Students for Life ambassador Isabel Brown warned people "it’s probably time to stop" drinking tap water in a May 1 Instagram video.

The reason? She said traces of the drug remain in the U.S. water supply after they pass through a woman’s body.

"Those active metabolites stay active in our wastewater and go on to poison our water, our soil, our plant life and our animal life," Brown said. "Plus medical waste of human tissue and human remains are being flushed down into our toilets and our bathtub drains, into our wastewater systems rather than being disposed of through a medical waste review process."

Students for Life on April 19 filed a citizen petition imploring the Food and Drug Administration to conduct an environmental study, arguing that it hasn’t done one in over 20 years.

The group’s campaign comes as a federal appeals court takes up a Texas court case challenging the FDA’s approval of mifepristone, which is FDA-approved for use with another drug, misoprostol, up to 10 weeks of pregnancy. The case is expected to reach the U.S. Supreme Court.

Environmental scientists and engineers told PolitiFact there is no evidence that mifepristone has harmed the environment or people via wastewater.

"There is absolutely no evidence that this is an environmental issue," said Nathan Donley, the environmental health science director for the Center for Biological Diversity. "Pharmaceutical waste can be a big issue when we're talking about widely used drugs, but to somehow point to mifepristone as a bad actor here is completely disingenuous."

Students for Life cited one scientific paper in its petition that identified at least three active metabolites, or byproducts, in mifepristone that can remain active after passing through a person’s system. But this is typical of many pharmaceuticals. It is not a sign that the drug is harmful.

"It’s certainly not uncommon" for substances to maintain some original activity as they degrade, said Heather Preisendanz, an agricultural and biological engineering professor at Penn State University. "It’s often true even for things that aren't pharmaceuticals."

Experts said the focus on mifepristone should be placed on more widely used pharmaceuticals that pose a confirmed environmental threat.

PolitiFact dug into the student group’s arguments about mifepristone’s effects on water and marine life.

Environmental engineers test U.S. wastewater and drinking water, with research often funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency or state environmental organizations.

Tom Young, a civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of California, Davis who conducts trace chemical analyses in the environment, said he has "zero reason" to think mifepristone is more harmful than other drugs just because traces of it may remain in wastewater.

This is "true of every drug we take," he said.

Young said the three metabolites referred to in the study the group cited aren’t included in databases used by his peers — meaning, they are not widely tracked like other contaminants — but he said that it’s common for active trace pharmaceutical chemicals to be present in wastewater. The tests, meanwhile, can pick up the original mifepristone compound, which Young said he hasn’t seen in California wastewater.

The EPA highlighted a series of studies on different prescription pharmaceuticals in wastewater, surface water and drinking water, noting that it works with various federal and state agencies to keep drinking water safe.

"Across hundreds of samples and more than a decade of data, these studies found pharmaceutical concentrations to be extremely low in wastewater," the agency wrote in the statement.

The EPA said it measured around 100 pharmaceuticals and calculated the predicted environmental maximum concentrations for all approved prescriptions. Even the most prescribed medications are used by less than 10% of the population, the agency said, and only a fraction of a dose is excreted in someone’s urine.

"There is a very large dilution factor, considering the volume of all the water in a community wastewater system," the agency said. "That wastewater is treated before discharge into surface and other receiving waters, where further dilution occurs. Those surface and other source waters are further treated before becoming drinking water."

To put these concentrations into perspective, depending on the drug, it would take months to decades of drinking two liters of raw, untreated wastewater per day to expose a person to a single dose, the EPA said.

According to Students for Life, the federal government failed to adequately study the effects of mifepristone on the environment before it was approved for use in 2000.

"We know from (Freedom of Information Act) requests that wastewater operations in the U.S. don't check for (these metabolites)," Kristi Hamrick, the group’s chief policy strategist, told PolitiFact by email. "The FDA did not do REQUIRED testing to determine the impact on endangered species."

The FDA is required under the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 to consider the environmental impacts of approving new drugs and biologics as part of its regulatory process.

The agency conducted an environmental assessment for mifepristone in July 1996 and said its predicted environmental concentration was less than one part per billion, the threshold under which concentrations are routinely found to have "no effect" on test organisms. It concluded that the drug could be used and disposed of "without any expected adverse environmental effects" and said adverse effects "were not anticipated for endangered or threatened species." But Students for Life asserts that the assessment is lacking and outdated.

When we asked the FDA about Hamrick’s claims, a spokesperson for the agency told PolitiFact that it generally doesn’t comment on pending petitions and will respond directly to the petitioners. Responses will be posted in the petition docket, the agency said.

Environmental law groups did not respond to PolitiFact’s questions about whether the FDA failed to adequately test for mifepristone-related environmental harms.

But Young said the group’s claims about the FDA seem misplaced.

"Wastewater fate is usually never part of pharmaceutical assessment," he said, "but there's been decades of research by people like me who have documented all the chemicals present in wastewater."

In its petition, Students for Life wrote that "many studies and organizations have already found that Mifepristone and other pharmaceuticals have an adverse effect on animal and aquatic life."

But most of the research cited didn’t appear to study, or mention, mifepristone. Many of the papers covered the environmental impact of hormonal contraception, which the group said was included to argue that the impact of abortion pills is also worth studying.

One 2018 study out of Czechia cited in the petition is mostly about progestins, a hormone that helps maintain pregnancy. Lead author Pavel Šauer, a researcher at the University of South Bohemia’s Faculty of Fisheries and Protection of Waters, said the group using his report as evidence of the drug’s environmental harm on animals or aquatic life is a "misinterpretation."

Šauer said the team tested only for the occurrence of mifepristone in wastewater and surface waters. He said that these tests cannot assess how the drug affects marine life.

"Since we have neither tested mifepristone on (living) aquatic organisms, nor performed risk assessments, conclusions cannot be drawn from our study’s results regarding any adverse effects of mifepristone on aquatic animals," he wrote in an email.

Šauer said the confusion may have stemmed from researchers searching water for "anti-progestogenic activity" and referencing unknown compounds that showed these effects as "so-called mifepristone equivalents." Anti-progestogenic refers to any blocking of the progesterone hormone, which is essentially mifepristone’s function in the two-drug abortion medication.

Mifepristone itself was found in only one plant’s raw untreated wastewater, and it didn’t contribute much (about 7.8%) to the overall anti-progestogenic activity, he said. The compound was removed after the wastewater was treated.

Students for Life referenced another study by Finnish researchers who looked at how humans metabolized the drug. The research, published in 2003, found that some metabolites still had activity in people — but it did not include findings or data about the shedding of mifepristone or its metabolites in urine.

One 2019 study from China claimed that mifepristone exposure can affect fish, but some experts questioned its methodology. These researchers added very high concentrations of mifepristone to the fish’s diets, which is not how the animals would be exposed to the drug in the environment.

"Exposure from wastewater would all be passive from the surrounding water. They wouldn’t be eating it. And they would be exposed to much lower concentrations in wastewater, if mifepristone even makes it into wastewater at all," Donley said.

Asked about Students for Life’s claim that at-home medication abortions constitute improperly disposed of medical waste, Hamrick said that abortion providers can’t flush placenta tissue or human remains down the toilet, but medication abortions "send women home to flush away chemically tainted blood, placenta tissue, and human remains." Hamrick said this differs from miscarriages, since those incidents cannot be planned and the tissue isn’t "chemically tainted."

But Young, from UC Davis, called the term "chemically tainted" ridiculous in this scenario, because drugs don’t typically accumulate in the body.

"Most medicines don't do this because that would be really bad for our health. We excrete them. They don't pile up in an embryo or in the tissue," he said. "I mean, fecal matter is loaded with stuff that makes people sick. That's why we disinfect wastewater."

Our Sources

Instagram post, May 1, 2023

Associated Press, What’s next for abortion pill after Supreme Court’s order, April 22, 2023

Associated Press, 3 judges who chipped away abortion rights to hear federal abortion pill appeal, May 16, 2023

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Environmental assessment and finding of no significant impact for NDA 20-687 Mifepristone tablets, July 1996

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Environmental Assessment of Human Drug and Biologics Applications, July 1998

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Environmental Impact Review at CDER, Oct. 24, 2022

U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Assessing effects of drugs in wastewater on aquatic wildlife, Updated Sept. 26, 2019

Politico, The next abortion fight could be over wastewater regulation, Nov. 23, 2022

Students for Life citizen petition, April 19, 2023

Politico, Anti-abortion group launches new pill challenge as SCOTUS mulls sweeping restrictions, April 19, 2023

Science Direct, Two synthetic progestins and natural progesterone are responsible for most of the progestagenic activities in municipal wastewater treatment plant effluents in the Czech and Slovak republics, June 15, 2018

Contraception, The pharmacokinetics of mifepristone in humans reveal insights into differential mechanisms of antiprogestin action, December 2003

Aquatic Toxicology, Effects of long term antiprogestine mifepristone (RU486) exposure on sexually dimorphic lncRNA expression and gonadal masculinization in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), October 2019

PIRG.org, ‘Bracing for Superbugs’ report highlights antibiotic resistance in the environment, Feb 7, 2023

Phone interview, Heather Preisendanz associate professor of agricultural and biological engineering at Penn State University, May 16, 2023

Phone interview, Thomas Young civil and environmental engineering professor at the University of California-Davis, May 16-17, 2023

Email interview, Nathan Donley, environmental health science director for the Center for Biological Diversity, May 16-23, 2023

Email interview, Kristi Hamrick chief policy strategist for Students for Life, May 16-18, 2023

Email interview, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency press office, May 16-18, 2023

Email interview, U.S. Food and Drug Administration press office, May 16-31, 2023

Email interview, Pavel Šauer, a faculty member of fisheries and protection of waters at the University of South Bohemia, May 16-17, 2023