Get PolitiFact in your inbox.

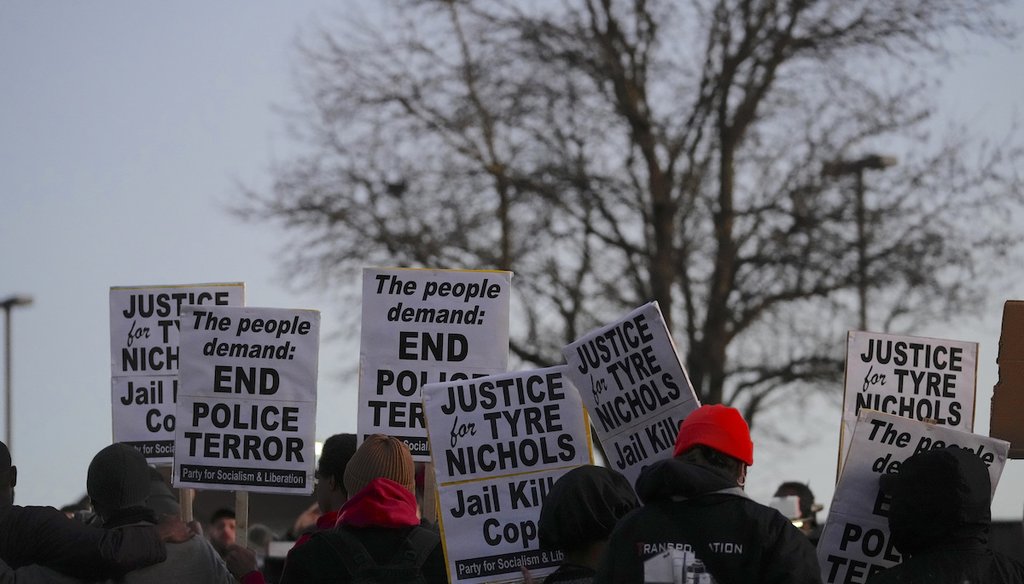

Protesters gather on Jan. 27, 2023, in Memphis, as authorities were set to release police video of the beating of Tyre Nichols, whose death resulted in murder charges and provoked outrage at the country's latest instance of police brutality. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

There is no reliable, government-sponsored national data collection system that tracks fatal encounters with police, and existing databases count fatal police incidents in differing ways.

-

Researchers disagree about what the available data shows about fatal encounters with police. Some say unjustified police violence was substantially worse in prior decades, while others say modern data shows that far more Americans are killed by police today.

-

Understanding the full extent of police use of deadly force would be possible only with more complete and accurate government data, criminology experts said.

High-profile police killings of unarmed people like George Floyd and Tyre Nichols thrust police brutality into the center of American discourse. But there’s a central question the U.S. appears to be unequipped to answer: Are more people dying at the hands of law enforcement now than ever?

One Jan. 7 story by British newspaper The Guardian claimed so — 2022 was a "record high," with at least 1,176 people killed by police, it said.

Days later, an article in the libertarian magazine Reason said the opposite: It wasn’t a record high because the database cited in The Guardian story dated only to 2013. The article argued that, historically, fatal encounters with police used to be significantly higher.

PolitiFact readers wanted to know which story is accurate.

The answer is: We don’t know. Data is a tricky thing, especially when there isn’t enough of it.

Databases such as Mapping Police Violence (where The Guardian sourced its numbers) and The Washington Post’s Fatal Force collection offer solid data on the current state of fatal police encounters. But several factors make it difficult and problematic to draw broad conclusions about long-term trends.

Here’s what we found.

Criminologists told us that the biggest issue with evaluating U.S. police use of deadly force is the lack of a reliable, government-sponsored national data collection system.

The data that is collected is incomplete and appears to reflect a significant undercount.

"It’s harder to fight the problem if we don’t have the data, because we don't know the exact scope of the problem," said Geoffrey Alpert, a University of South Carolina criminology and criminal justice professor. "There are just so many variables, it all comes back to us not really knowing."

The Federal Bureau of Investigation and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention keep tabs on deaths resulting from interactions with police, but both sources provide insufficient data that doesn’t come close to capturing all police-related killings.

In 2019, the FBI launched its National Use-of-Force Data Collection, but law enforcement agencies aren’t required to participate. Initial data released in July 2020 came from agencies representing only around 41% of law enforcement officers nationally. In Florida alone, just two of 757 law enforcement agencies contributed data.

The CDC data, meanwhile, is based on death certificates that coroners and medical examiners are required to file for all "sudden unexpected deaths," including homicides. Medical examiners and coroners can note whether a homicide resulted from a law enforcement encounter, but the practice isn’t systematic and many incidents end up misclassified, said the Brady Center to Prevent Gun Violence, a nonprofit that supports restrictions on guns.

The Justice Department’s Bureau of Justice Statistics is responsible for collecting and publishing information on crime and the operation of justice systems at all levels of government. But the agency "does not have a comprehensive data source on police killings," a spokesperson told us.

Recognizing this information chasm, journalists, researchers and others have sought to fill in the blanks.

The website Fatal Encounters, launched by a journalist in 2012, used crowdsourced information, public records and news reports, and covered 2000-2021 until it stopped tracking deaths in December 2021.

The Washington Post in 2015 started its own project focused only on fatal police-involved shootings. Researchers mine local news reports, law enforcement websites and databases such as Fatal Encounters for relevant information.

The Mapping Police Violence website founded by data scientist and racial justice activist Samuel Sinyangwe, began tracking police killings in 2013. Its data includes people who died after being shot, beaten, restrained or stun-gunned by police.

As of Jan. 31, 2023, Mapping Police Violence reported that 1,192 people had been killed by police in 2022. The Post found that there were 1,096 fatal police shootings in 2022. The CDC has released provisional 2022 data, but the agency told us its numbers are still incomplete. As for the FBI, the agency’s voluntary database was still incomplete in 2022.

These figures alone don’t speak to the circumstances of the individual encounters. Police killings that are determined to be unjustified capture most of the media attention. But some of the incidents included in these numbers involve situations when police killed people who posed legitimate threats to the public — when investigators believe the officers’ actions were justified.

Daniel Nagin, a public policy and statistics professor at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College, is familiar with The Washington Post’s database and said the descriptions included with its data make it clear that many of the police killings aren't unwarranted.

"Based on the descriptions that are given, many of these incidents don't jump out as encounters that are uncalled for," Nagin said. "Now, that doesn’t mean that some of them weren’t, like the incidents with George Floyd and Tyre Nichols, but I think it’s an important, nuanced point."

So how did researchers arrive at such different conclusions?

Reason’s article cited data compiled by Peter Moskos, an associate professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice and former Baltimore police officer, to support its argument that fatal encounters with police used to be much higher.

Moskos used data going back to the 1970s combined with modern data from the Fatal Encounters database, and included only fatal incidents involving firearms. He compiled his historical data from individual police departments, with some of the largest agencies providing detailed annual reports.

This data does not allow for an exact comparison with 2022, because there weren’t nationwide figures from the 1970s. Moskos’ analysis was of officer-involved shootings in 18 cities.

His analysis showed a 69% reduction in the rate of officer-involved fatal shootings per 100,000 people in those 18 cities since the 1970s. He also said the decrease in the cohort he examined is significant enough that it can be extrapolated to cities across the nation.

For example, Moskos found that from 1970 to 1974, New York City police shot and killed an average of 62 people per year. From 2015 to 2021, that number decreased to an annual average of nine people — even as the city population grew by about 1.2 million people.

Frank Edwards, an assistant professor at Rutgers University’s school of criminal justice, however, said the picture that emerges using Moskos’ data is problematic for two reasons: It draws conclusions based on a limited number of cities and compares per capita rates to total incident counts.

Based on the years for which unofficial, accurate measurement is available — since about 2010 — 2022 does appear to have the highest number of police killings on record, Edwards said.

"The best available research estimating historical trends suggests that the count of deaths is higher now than in the past," Edwards said, referring to a 2021 study published in The Lancet medical journal.

That study analyzed information from unofficial databases including Fatal Encounters and Mapping Police Violence and compared it with the government’s National Vital Statistics System data to determine the extent of underreporting.

The researchers reported that they found a 38% increase in fatal police violence of all kinds since 1980, though they noted the difficulty of working with limited historical data.

The Washington Post reported in December 2022 that its database showed "officers have shot and killed more people every year, reaching a record high in 2021 with 1,047 deaths."

When asked whether police use of force was worse in prior decades than today, Nagin from Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College said many variables muddy the picture.

"There were fewer weapons back then, and the ones that were around were far less lethal," he said. "But on the other hand, this was also a time when police were far less disciplined about use of force in their interactions with citizens, particularly with minorities. And so those seem to me two counter-balancing forces. I simply don't know."

That experts cannot agree on what the data shows reveals the root of the problem.

"It’s a national embarrassment that we don’t know exactly how much deadly force is used by the police," said Alpert, the University of South Carolina criminology professor. "The government knows more about how we spend money than how we use deadly force. I think that shows where our misplaced emphasis is."

UPDATE 2/9: This story has been updated to reflect the CDC's response about its 2022 numbers.

Our Sources

The Guardian, ‘It never stops’: killings by US police reach record high in 2022, Jan. 6, 2023

The Reason, Police Killed 1,183 People in 2022. Despite a Viral Claim, That's Not a 'Record High.', Jan. 12, 2023

Mapping Police Violence, Accessed Jan. 30, 2023

Washington Post, 1,110 people have been shot and killed by police in the past 12 months, Updated Jan. 25, 2023

Fatal Encounters, Accessed Jan. 30, 2023

University of Illinois Chicago, Demographics of civilian deaths from contact with law enforcement, Accessed Jan. 31, 2023

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WISQARS™ — Web-based Injury Statistics Query and Reporting System, Accessed Jan. 30, 2023

Al Jazeera, Know their names: Black people killed by the police in the US, Accessed Feb. 3, 2023

Federal Bureau of Investigation, National Use-of-Force Data Collection, Accessed Jan. 30, 2023

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Risk of being killed by police use of force in the United States by age, race–ethnicity, and sex, August 5, 2019

National Library of Medicine, Quantifying underreporting of law-enforcement-related deaths in United States vital statistics and news-media-based data sources: A capture-recapture analysis, October 2017

The Lancet, Fatal police violence by race and state in the USA, 1980–2019: a network meta-regression, published Oct. 2, 2021

The New York Times, More Than Half of Police Killings Are Mislabeled, New Study Says, Sept. 30, 2021

Email interview, Frank Edwards, assistant professor at the School of Criminal Justice at Rutgers University in Newark, Jan. 30-31, 2023

Phone and Email interview, Peter Moskos, an associate professor at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, Jan. 30-Feb. 1, 2023

Phone interview, Geoffrey Alpert, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of South Carolina, Jan. 31-Feb. 2, 2023

Phone interview, Daniel Nagin, professor of public policy and statistics at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College, Feb. 2, 2023

Email interview, Belsie Gonzalez spokesperson at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Feb. 2-3, 2023