Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

A speaker walks to the podium during a session for the 2023 World Artificial Intelligence Conference held in Shanghai, Thursday, July 6, 2023. (AP)

If Your Time is short

-

Ahead of the 2024 elections, experts are warning that foreign adversaries can use new generative artificial intelligence tools to conduct influence operations more efficiently and effectively. The new tools make it easier and cheaper to produce fabricated content such as political messages, profile photos, video footage and audio.

-

New generative AI tools are better able to create seemingly authentic content, which is harder for humans or machines to easily detect.

-

One expert warned that deepfakes, generated images and voice cloning could be used to imitate political candidates and target other politicians, voters and poll workers.

We’ve seen it before: Foreign adversaries, seeking to influence U.S. elections, deploy bots and trolls to infiltrate social media platforms.

In 2016 and 2019, the Russian group Internet Research Agency created fake social media accounts to sow discord among U.S. voters in swing states, posting content about divisive topics such as immigration and gun rights.

Similar fake social media campaigns are already in progress: Last week, Meta said it removed 4,789 China-based Facebook accounts that were impersonating Americans. Meta said the accounts posted about U.S. politics and U.S.-China relations and criticized both sides of the U.S. political spectrum.

And with another election approaching, bad actors have a newly powerful tool to wield: generative artificial intelligence.

Generative AI — technology that lets computers identify patterns in datasets and create text, photos and videos — powers the increasingly popular text generator ChatGPT and text-to-image tools such as DALL-E and Midjourney.

Researchers at Rand Corp., a nonprofit public policy research organization, warned that these tools could jump-start the next generation of social media manipulation to influence elections. With these tools, content for influence campaigns — political messages, profile photos for fake accounts, video footage and even audio — is easier and cheaper to create.

We talked to experts who described ways generative AI could help foreign governments and adversaries influence U.S. political discussion and events.

Valerie Wirtschafter, a fellow in the Brookings Institution’s Foreign Policy program and the Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative, said generative AI will likely fuel mistrust.

"With the frenzied rollout of generative AI tools, we now live in a world where seeing may not actually be believing," she said.

Although Russia’s 2016 election interference targeted key voter demographics and swing states, Rand researchers predict that more sophisticated generative AI could make it possible for adversaries to target the entire U.S. with tailored content in 2024.

This November 2017 file photo shows some of the Facebook and Instagram ads linked to a Russian effort to disrupt the American political process and stir up tensions around divisive social issues. (AP)

What are influence operations?

Information operations are also called influence operations and information warfare. For Rand researchers, these operations involve adversaries collecting useful information and disseminating propaganda to gain a competitive advantage. Foreign governments use these operations to change political sentiment or public discourse.

The FBI, which investigates foreign influence operations, said the most frequent campaigns involve fake identities and fabricated stories on social media to discredit people and institutions.

Traditional media outlets sometimes cover these narratives unwittingly. In 2017, for example, the Los Angeles Times featured tweets from accounts operated by the Russian Internet Research Agency in an article about reaction to Starbucks Corp. pledging to hire refugees. One of these accounts misrepresented itself as the "unofficial Twitter of Tennessee Republicans."

One way to measure influence operations’ impact is examining how they seep from legacy and social media into real life. Ben Nimmo, former head of investigations at social media analytics company Graphika and now global threat intelligence lead at Meta, wrote that the most dangerous influence operations can spread to many different groups, across social media and other communications, including radio, TV, direct messages and emails.

What was previously possible

AI has been able to create fake faces since 2014, and experts said AI tools started being regularly used in 2019 to create deepfakes, or machine-generated image or video that makes people appear to do or say things they didn’t.

Experts said that year had the first publicly identified case of a fake face used in a social media campaign. In 2019, a network of Facebook accounts using AI-generated profile photos posted about political issues including former President Donald Trump’s impeachment, conservative ideology and religion.

This image made from video of a fake video featuring former President Barack Obama shows elements of facial mapping used in new technology that lets anyone make videos of real people appearing to say things they've never said. (AP)

Kenton Thibaut, resident China fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, said China used generative AI on a smaller scale in 2019 and 2020 to generate profile photos for bot pages or "sock puppet accounts" — which are operated by people but misrepresent who’s behind them.

Images on these accounts were easy to detect as fake, Thibaut said, because they featured telltale signs such as distorted ears or hands, which was a common problem with that generation of software.

Reliance on human labor also made AI-generated content in previous large-scale influence campaigns easier to detect as artificial, Rand researchers said. Messages tended to be repetitive, and this repetition led to the identification and removal of these networks. Newer AI tools make it easier to create more content, so it isn’t necessary to rely on one set of messages crafted by humans.

Cheaper and less labor-intensive influence operations

Disinformation campaigns from the 2010s needed humans at every stage — from developing a concept to designing material and spreading it across social media.

Generative AI automates these processes, making them cheaper and requiring fewer people.

"The types of people who conduct such campaigns will be similar to those who led these operations in the past, but the cost of producing content will be significantly lower," said Wirtschafter. "What would maybe take a team of 40 people to produce might now just take a few."

AI also can be used to more efficiently translate information, Thibaut said. This can aid people outside the U.S. who are conducting influence campaigns within the U.S.

New technology helps fine-tune more personalized messages

With the launch of tools such as ChatGPT in 2022, Thibaut said China has been pursuing more precise communication techniques. That means forgoing generic pro-China, anti-U.S. narratives and tailoring narratives based on audiences’ local interests and needs. This way, the messages resonate.

Thibaut pointed to Wolf News, a media company Graphika described as "likely fictitious." Graphika discovered that Wolf News was featured in a pro-Chinese political spam operation that was using AI-generated news anchors. In one video, a news anchor discussed the frequency of mass shootings in the U.S.; in another, an anchor promoted China’s talks with other nations.

Pro-China bots’ distribution of these videos was the first reported instance of using deepfake video technology to create fictitious people for a state-aligned influence operation, according to Graphika and The New York Times.

Rand Senior Engineer Christopher Mouton wrote that U.S. adversaries could manipulate AI models to sound "truthy," crafting humanlike, coherent, well-structured and persuasive messages.

Sophisticated generative AI and elections

Wirtschafter said adversaries could use AI in last-minute attempts to disenfranchise voters. In the past, alarming false claims that spread on social media misled people about what would happen when they go to in-person polling places, or if they vote by mail.

Wirtschafter said deepfakes, generated images and voice cloning could be used to imitate candidates running for office and could target political candidates, voters and poll workers. These fakes would be harder to detect in state and local races compared with higher-profile national races, she added.

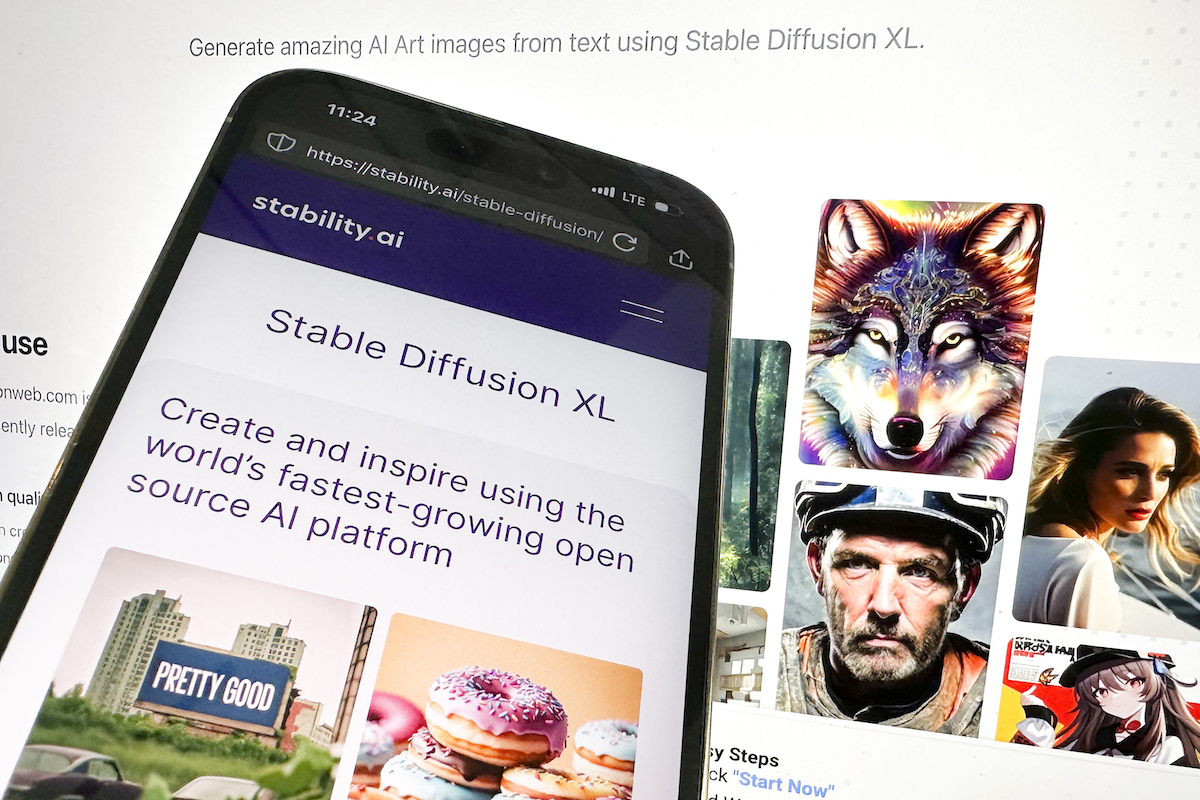

This photo shows the desktop and mobile websites for Stable Diffusion. (AP)

Wirtschafter also said AI could be used to manufacture a last-minute news event. She mentioned a case two days before a Slovakia election in which a fake audio recording was released and fact-checkers scrambled to debunk the claims. The fake audio discussed how to rig the election and mimicked the voices of the liberal Progressive Slovakia party’s leader and a journalist.

"This type of last-minute effort could be a looming threat in the 40 different elections (in 2024) taking place around the world, where some media have less capacity to fact check and disseminate clarifying information rapidly," she said.

However, Munira Mustaffa, founder and executive director of Chasseur Group, a consulting company specializing in security challenges, said although it is almost certain AI will be used to influence voter opinions, it may have less effect than confirmation bias — people favoring information that aligns with their beliefs.

"Strategies to combat election-related disinformation should focus more on addressing this underlying cognitive bias, fostering critical thinking and information literacy among the electorate, rather than solely depending on tech solutions to counter falsehoods," she said.

Our Sources

Rand Corp., Information Operations, accessed Nov. 8, 2023

NBC News, 'Information warfare': How Russians interfered in 2016 election, Feb. 16, 2018

Brennan Center for Justice, New Evidence Shows How Russia’s Election Interference Has Gotten More Brazen, March 5, 2020

MIT Technology Review, Why detecting AI-generated text is so difficult (and what to do about it), Feb. 7, 2023

The New York Times, 4,789 Facebook Accounts in China Impersonated Americans, Meta Says, Nov. 30, 2023

Meta, Third Quarter Adversarial Threat Report, November 2023

Brookings Institution, The Breakout Scale: Measuring the impact of influence operations, September 2020

Los Angeles Times, Supporters and opponents of Trump’s refugee ban take to social media to put pressure on companies, Jan. 30, 2017

FBI, Combating Foreign Influence, accessed Nov. 15, 2023

PolitiFact, What is generative AI and why is it suddenly everywhere? Here’s how it works, June 19, 2023

PolitiFact, How to detect deepfake videos like a fact-checker, April 19, 2023

The Associated Press, Experts: Spy used AI-generated face to connect with targets, June 13, 2019

Kai-Cheng Yang and Filippo Menczer, Observatory on Social Media, Indiana University, Anatomy of an AI-powered malicious social botnet, July 30, 2023

Wired, Where the AI Art Boom Came From—and Where It’s Going, Jan. 12, 2023

Reuters, These faces are not real, July 15, 2020

Reuters, Microsoft chief says deep fakes are biggest AI concern, May 25, 2023

The New York Times, Facebook Discovers Fakes That Show Evolution of Disinformation, Dec. 20, 2019

Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers, The Next Generation of Cyber-Enabled Information Warfare, 2020 12th International Conference on Cyber Conflict

Reuters, China suspected of using AI on social media to sway US voters, Microsoft says, Sept. 7, 2023

Graphika, Deepfake It Till You Make It: Pro-Chinese Actors Promote AI-Generated Video Footage of Fictitious People in Online Influence Operation, Feb. 7, 2023

The New York Times, The People Onscreen Are Fake. The Disinformation Is Real., Feb. 7, 2023

Rand Blog, ChatGPT Is Creating New Risks for National Security, July 20, 2023

PolitiFact, Fact-checking a claim about when your mail ballot is due, Oct. 20, 2020

PolitiFact, Instagram Posts Make False Claim CA Voters Will Be ‘Turned Away’ From Polls Due To Mail-In Voting, Sept. 1, 2020

PolitiFact, Michigan officials decry ‘racist’ robocall with false attacks on mail-in voting, Aug. 31, 2020

Wired U.K., Slovakia’s Election Deepfakes Show AI Is a Danger to Democracy, Oct. 3, 2023

Bloomberg News, In 2024, It’s Election Year in 40 Countries, Nov. 16, 2023

Email interview, Valerie Wirtschafter, fellow in Foreign Policy and the Artificial Intelligence and Emerging Technology Initiative at Brookings Institution, Nov. 14, 2023

Zoom interview, Kenton Thibaut, resident China fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, Nov. 14, 2023

Email interview, Munira Mustaffa, founder and executive director of Chasseur Group, Nov. 15, 2023