Stand up for the facts!

Our only agenda is to publish the truth so you can be an informed participant in democracy.

We need your help.

I would like to contribute

President Joe Biden, front left, and U.K. Prime Minister Boris Johnson, front right, with European Council President Charles Michel, back left, Japan's Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, back center, and Italy's Prime Minister Mario Draghi.

If Your Time is short

• Since 2013, China has been pursuing a “Belt and Road Initiative” to leverage its industrial capacity to help developing countries build out their physical and digital infrastructure.

• Many nations in the West worry that the initiative could tilt international commerce and geopolitics in China’s direction, with long-lasting consequences.

• At their summit in mid-June, G-7 leaders launched the “Build Back Better for the World” initiative, which is aimed at countering Belt and Road and offering stronger standards for government transparency, environmental protection, and the ability to avoid dependence on China’s authoritarian government.

At their recent summit in Cornwall, England, the G-7 countries backed an effort to offer an alternative to the "Belt and Road Initiative," China’s sprawling, eight-year-old effort to build physical and digital infrastructure in other countries.

The G-7 effort, called "Build Back Better for the World," or B3W for short, is being championed by President Joe Biden as a way to counter China’s authoritarian government and growing global influence. ("Build Back Better" was one of Biden’s 2020 campaign slogans to promote U.S. infrastructure investment.)

The G-7 countries — Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States — say they want to offer other nations that want to improve their infrastructure an alternative to partnering with China, an alternative that comes with stronger standards for government transparency, environmental protection, and a role for local leadership.

Despite its vast reach, China’s Belt and Road Initiative is not widely known among Americans outside foreign-investment and diplomatic circles. But the project’s potential implications for the future of global commerce and geopolitics have suddenly placed it near the top of the West’s policy agenda.

"Even Chinese scholars argue about the program’s goals and efficacy," said Robert Daly, director of the Wilson Center's Kissinger Institute on China and the United States. "It is a work in progress with a mixed record. But it has captured attention worldwide and is a major driver of global discussions about connectivity and development."

Here’s a rundown on what the Belt and Road Initiative does, why the G-7 nations are worried about it, and the promise — and the limits — of the Western counter-effort announced at the summit.

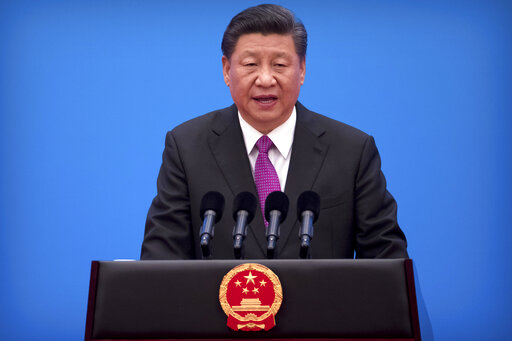

Chinese President Xi Jinping at a press conference to close the Belt and Road Forum at Yanqi Lake near Beijing on April 27, 2019. (AP)

What is the Belt and Road Initiative?

The project’s name comes from Chinese President Xi Jinping's vision for a "Silk Road Economic Belt" that references the centuries-old Silk Road that ran as a trading route from northern China through central Asia and extended to the Mediterranean Sea, where goods could be shipped to Europe.

Xi announced the effort in a pair of speeches in 2013. It began as an effort to use infrastructure to link China’s modern coastal cities to its less-developed interior regions and to its immediate neighbors. The initiative has since expanded to Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America. It even has a toehold in Europe.

In most cases, Chinese banks have provided financing, and Chinese companies have handled construction for a wide range of traditional infrastructure projects, including power plants, railways, highways and ports. A "digital Silk Road" component has focused on building out telecommunications, artificial intelligence capabilities, cloud computing, electronic commerce and surveillance technology.

Despite its umbrella name, experts say the Belt and Road Initiative is more diffuse than might be expected from a country with a reputation for government centralization.

"There isn’t even a single ministry tasked with overseeing it — there are multiple ministries," said David Sacks, a research fellow at the Council for Foreign Relations and one of the authors of a task force report on the initiative. "We think it’s better to understand it as a branding exercise."

China has not published a master list of projects, leaving experts outside of China to guess about its size and reach from bits and pieces of publicly released information. The best estimates suggest that 140 countries are participating in the initiative in some fashion, although the extent of participation varies widely, said Jonathan E. Hillman, a senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and author of the book "The Emperor's New Road."

"In many ways, what the research has shown is that it’s a fragmented set of initiatives," said Alvin Camba, an assistant professor at the Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver.

The Guardian cited data from the firm Refinitiv that suggests the initiative has involved more than 2,600 projects with a collective value of $3.7 trillion.

Projects under the initiative declined during the coronavirus pandemic and the ensuing recession. Still, in inflation-adjusted spending, the Belt and Road Initiative "dwarfs" the Marshall Plan, the United States’ post-World War II effort to rebuild Europe, Sacks said.

Sacks said that China "strenuously" objects to any comparison of the Belt and Road Initiative to the Marshall Plan, arguing that the Marshall Plan had geopolitical goals that the Belt and Road Initiative does not. Most Western analysts reject the assertion that no geopolitics is at play in China’s efforts, but they add that the Chinese initiative does have a mixture of motivations, not all of them geopolitical.

Why is China pursuing the Belt and Road Initiative?

A major reason for launching the Belt and Road Initiative was a desire to use China’s industrial "overcapacity" in certain sectors such as construction. China’s industrial companies, many of them state-owned, had expanded their capabilities to meet domestic infrastructure needs, and government and business officials came to see building infrastructure in the developing world as a way to more fully utilize the assets they’d already invested in. Similarly, Chinese banks saw the financing of foreign projects as a way to put the nation’s savings to work.

In turn, these overseas projects helped strengthen "a wider web of trade, investment and commercial ties to countries in its region and farther afield," said Daniel S. Markey, a senior research professor in international relations at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies. Not surprisingly, the trade routes resulting from the new infrastructure are generally pointed in China’s direction.

Meanwhile, these commercial linkages were widely seen as bolstering the country’s international clout.

"Investments and cooperation through the Belt and Road Initiative build China's stature as a global player and put it into routine engagement with other states as a benefactor, investor and creditor," Markey said.

All in all, the initiative was "part of China building a narrative that it is the world’s ascendant economic power, and that the United States and the West are has-beens," Sacks said.

Perhaps the largest single partner in the initiative is Pakistan, where the leaderships of both countries are hoping that structural investments can increase political stability and reduce threats posed by radicalization. The projects have included energy, transportation and digital infrastructure efforts.

Although the projects in Pakistan have had their share of "frustrations, delays and challenges," Markey said, "leaders in Islamabad continue to see its success as critical to Pakistan's own economic development and the bilateral relationship with Beijing as increasingly important to their strategic posture in the region."

Even some European nations have dipped a toe into the Belt and Road Initiative. Italy signed up as a partner in 2019, though it later stepped back under pressure from Western allies, vetoing a 5G agreement involving Huawei. (5G is the new technology standard for broadband cellular networks.)

Montenegro contracted with China to build a highway to neighboring Serbia, but work stalled, and Montenegro is now asking the European Union to help to repay its debt, so far to no avail.

Why are the United States and other Western nations worried about the initiative?

Even its skeptics acknowledge that the Belt and Road Initiative is serving a demonstrated need for development projects across the globe. The World Bank has pointed to an $18 trillion "infrastructure gap" between what’s needed and what’s being provided for already.

"If implemented sustainably and responsibly, (the Belt and Road Initiative) has the potential to meet longstanding developing country needs and spur global economic growth," the Council on Foreign Relations report concluded.

However, the same report cited several risks that, collectively, "considerably outweigh its benefits."

Here are some of the frequently raised concerns:

• Projects under the Belt and Road Initiative aren’t as transparent as those organized by traditional organizations like the World Bank.

The initiative "flouts best practices areas like transparent governance, environmental standards and labor rights," Daly said.

Notably, China "doesn’t generally conduct rigorous economic or environmental or social-impact studies first," Sacks said. "If the customer wants it, they will build it. They will lend to autocrats. If an autocrat wants a soccer stadium, they’ll build it, even if it’s a vanity project."

• China can build infrastructure based on its own technologies and standards, which gives it a competitive edge in future rounds of development, especially in digital networks.

"If a country is using 5G technology from Huawei (a Chinese company), it comes with technical specifications that make it much more likely that when the country is ready for 6G, they will either have no choice but to use Huawei technology, or at least it will be the cheaper option," Sacks said.

Some Western nations have said that telecommunications systems based on Chinese technology could be vulnerable to spying, especially with the broad surveillance networks that have been built under the initiative. Surveillance systems "won’t turn a democracy into an autocracy, but they can help non-democratic leaders cement their control," Sacks said.

• The energy projects so far have been predominantly carbon-based rather than renewable.

This tendency has "the potential to lock countries into decades of non-renewable energy sources," Sacks said, marking a disconnect between China’s claims on the global stage that it supports a move toward reducing carbon emissions.

• Countries can be left heavily indebted to China.

One oft-cited example is the Hambantota Port in Sri Lanka, where the host country was unable to repay the loans, and China instead got a 99-year lease for the port.

However, even critics of the Belt and Road Initiative acknowledge that the Sri Lanka example is not a clear-cut indictment of China. The deal was struck before the initiative was launched, and the story "implicates local Sri Lankan officials who chose to work with China to advance their own political interests," Markey said.

In fact, research by Deborah Brautigam, director of the China-Africa Research Initiative at Johns Hopkins University, suggests that there is no evidence of Chinese banks systematically over-lending to swoop in and seize assets once borrowers default.

Still, multiple aspects of the initiative run counter to Western interests, Markey said.

"While not every aspect is worrisome or even likely to conflict with U.S. or allied interests, as a whole it poses a strategic challenge that requires some sort of thoughtful policy response," he said.

What did the G-7 nations do to counter the Belt and Road Initiative?

At their June summit, the G-7 nations put forth a plan to offer an alternative to the Belt and Road Initiative. A White House statement described it as a "values-driven, high-standard and transparent infrastructure partnership led by major democracies" that would stretch from "Latin America and the Caribbean to Africa to the Indo-Pacific."

The United States was cited as the "lead partner," leveraging such existing entities as the Development Finance Corp., the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Export-Import Bank, the Millennium Challenge Corp., and the U.S. Trade and Development Agency to support the mission.

Experts described the "Build Back Better for the World" program as a good first step, but they also warned about its limitations. For instance, the G-7 leaders did not initially specify a top-line figure for investments, and some observers called it a "patchwork" effort that did not seek to leverage significant cooperation from institutions that have experience in global development, notably the World Bank.

A critical question, Hillman said, will be "whether they can more effectively mobilize private capital, which is where the real untapped financial firepower resides."

Another concern is that there may be no credible, reasonably priced alternative to China for certain types of projects, including 5G networks and high-speed rail, due to limited suppliers in the West, Sacks said.

Overall, Markey said he’s "underwhelmed" by the proposal so far — but he added that he’s also not too worried about that verdict at this point.

"I would prefer the U.S. and its friends not to try to compete with China on its own terms," Markey said. "It would be much better if the U.S. tries to compete with China in areas where it enjoys greater advantages. Vaccine diplomacy is much more important at the moment. Or educational exchanges, or support to overseas journalists. These are areas where the U.S. has ‘overcapacity’ to export in the same way as China has overcapacity in steel or concrete or railway cars. We're unlikely to win a competition if China's setting the terms."

Our Sources

White House, "Fact Sheet: President Biden and G7 Leaders Launch Build Back Better World (B3W) Partnership," June 12, 2021

White House, "Interim National Security Strategic Guidance," March 2021

Council on Foreign Relations, "China’s Belt and Road: Implications for the United States," March 2021

New York Times, "Biden Tries to Rally G7 Nations to Counter China’s Influence," June 12, 2021

Washington Post, "Montenegro mortgaged itself to China. Now it wants Europe’s help to cut it free," April 18, 2021

The Diplomat, "The Belt and Road in Italy: 2 Years Later," March 23, 2021

The Diplomat, "Is China’s Belt and Road Initiative a Threat to the US?" May 22, 2021

Foreign Policy, "China’s Diplomacy Is Limiting Its Own Ambitions," June 9, 2021

The Guardian, "G7 backs Biden infrastructure plan to rival China’s belt and road initiative," June 12, 2021

CNBC, "G-7 wants to rival China’s Belt and Road plan — but it won’t stop Beijing, expert says," June 14, 2021

Interview with Alvin Camba, assistant professor at the Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver, June 14, 2021

Email interview with Daniel S. Markey, senior research professor in international relations at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, June 14, 2021

Email interview with Robert Daly, director of the Wilson Center's Kissinger Institute on China and the United States, June 14, 2021

Email interview with Jonathan E. Hillman, senior fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, June 14, 2021

Interview with David Sacks, research fellow at the Council for Foreign Relations, June 14, 2021